My Sister, 23, Was Taken Out Into the Snow and Left to Die. It Was Never Properly Investigated

Two days after Danielle Ewenin learned that her 23-year-old sister had been found frozen to death in a farmer’s field on the outskirts of Calgary, Alberta, a city in southwestern Canada, she said she sat down with a police officer to try to understand how such a tragedy could have happened.

It was February 1982 and Danielle, 22, and her parents were inside a family member’s home in Regina, a city in Saskatchewan, Canada, when the local officer, who she said had been briefed by Calgary police, explained that her sister Eleanor “Laney” Ewenin was last seen leaving a downtown bar in Calgary. Two days later, police reportedly found her in a field that Danielle estimates would have been about 20 miles from the town center at that time.

“They had told us that it had snowed, so they could see the tire tracks pulling in and the tracks pulling out and that they could see that she was trying to make her way across the field,” said Danielle, who described the meeting with police as lasting about an hour. “There was a building there that had lights on, so they felt that that's where she was going.”

But she would never make it. Tracks in the snow, according to Danielle, indicated that she fell three times and on the third fall she never got back up.

The mother of two boys, ages 5 and 3, was found face down, dead in the snow after preceding nights dropped as low as -15F.

According to the autopsy provided by her family, Laney’s cause of death was hypothermia, with alcoholic intoxication listed as the “antecedent cause.” That same year her death was ruled non-suspicious, according to Alberta Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

But in the ensuing decades, family members have become convinced of a very different version of events; they say Laney was a victim of the so-called “starlight tours.”

The shocking practice, which has been documented many times in Canada, typically involves law enforcement officers driving an Indigenous person into a remote area and leaving them in freezing temperatures. Some have not survived these tours. Human Rights Watch reports that the practice dates back to at least 1976.

It was only when an Indigenous man named Darrell Night survived one such attack in 2000 —and the officers involved were convicted—that the practice received broader publicity. “Indigenous leaders reported receiving over 250 phone calls reporting incidents of ‘starlight tours’ across Saskatchewan,” according to Human Rights Watch.

Although it has been documented primarily in Saskatchewan, additional instances involving police indicate that the practice extends beyond this single province.

About a week before Laney’s body was discovered, family members said city police showed up at her mother’s home in Calgary with Laney.

This was a fairly common occurrence, according to Debbie Green, another of Laney’s sisters, who was around 12 at the time.

Laney, who is Plains Cree, was taken from her family as a young child as part of the “sixties scoop,” a series of policies that began in the early 1950s and resulted in the removal of thousands of Indigenous children from their homes. She suffered horrific abuse in foster homes, which included losing her left ring finger, and she later developed an alcohol addiction. Just before she died she was looking into alcohol treatment and getting custody of her sons.

Lillian Piapot, Chief commissioner Marion Buller of the MMIWG National Inquiry, Debbie, Mona Woodward, Danielle

Since she didn’t have a home of her own, when Laney would drink to excess in Calgary, the city police often brought her back to her mother’s house, according to Debbie. Calgary police say they have no records of this.

The last time police had brought her home, it was different, Debbie said: “The police came one time with her and said, ‘Look, we’re tired of doing this. You better do something, right? Or she's just not gonna make it home one day.’”

Days later, Laney Ewenin was dead.

The family believe she was another victim of the “starlight tours.”

They say the remoteness of where she was found, her history with law enforcement, and the fact that a family member reported seeing Laney get picked up by police before she disappeared, have led them inescapably to that conclusion.

They also say there were some glaring discrepancies with the police investigation; documents were filed under the wrong name, and her body was able to be quickly buried after a mysterious benefactor paid for it to be sent home.

Danielle told The Daily Beast that she believes the Calgary Police took her sister “on a ‘starlight tour,’ dropped her off, and that was the cause of her death.”

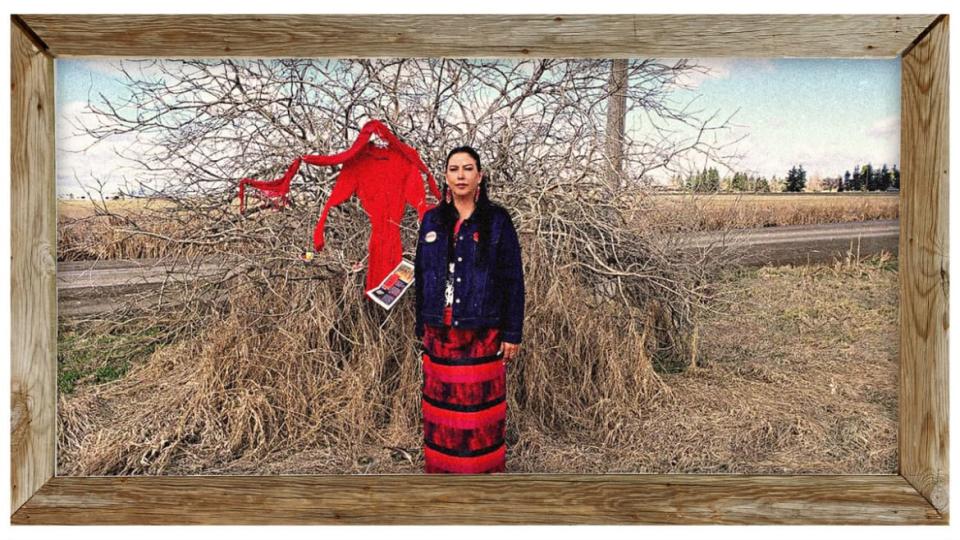

Debbie at the location where Laney was found.

Today, the family is pushing for answers and justice for Laney, who family members described as fun and fierce. They also want to raise awareness so something like this does not happen to any more Indigenous people.

“I want people to know about the ‘starlight tours’, that they happened, to believe the families when they say it happened, despite what the police or reports are saying, you know, and hold policing accountable,” said Debbie.

According to the certificate of the medical examiner and the autopsy report, Laney was found in jeans, leather snow boots, a down vest and a bomber jacket in a field near a rural road. Her only injuries were minor and appeared to be the result of crawling in the snow, the document states.

The report makes no mention of a vehicle, and instead describes foot tracks on the side of the road “for some distance.” It adds: “They then went into a field and made a wide curve finishing at the point where the body was found.”

In accordance with traditional protocols for burial, the family needed to have Laney buried within four days of her death. But she first needed to be transported about 500 miles from Calgary to Regina. This would have been a huge burden for the family, which was struggling financially, and other organizations that might have been able to help had rules at that time about transporting across provinces, according to the family. Danielle said she remembers facing huge barriers in the past when trying to bring the bodies of loved ones home.

Debbie at the location where Laney was found.

“But when we met with [police], they told her that she was already arriving, they just needed a funeral home, to know where to send her,” she said.

The family, according to Danielle, never found out who paid for the transportation nor how it was able to be done so fast.

A Calgary Police spokesperson said the agency had no involvement in the investigation of her death. A medical examiner report lists Royal Canadian Mounted Police Strathmore as the police force, but Alberta Royal Canadian Mounted Police explained that they were responsible for investigating.

Green said their brother, who has since died, told another one of their sisters that he had been out with Laney the night she disappeared and saw “the cops take her away that night.”

Danielle said one particular Calgary police officer had harassed her sister, and would pick her up regularly. But she said she didn’t know the name of the officer.

The Alberta Royal Canadian Mounted Police said it no longer had an investigation file related to Laney’s death. Since her death was ruled not suspicious, an Alberta Royal Canadian Mounted Police spokesperson said in an email the file “was subject to purging after eight years, in accordance with Canadian Federal Government information retention policies. Because of that policy, I don’t have any records to be able to confirm that the file existed in 1982.”

For years, Laney’s siblings tried to move forward from the tragedy. They would talk occasionally about it and the difficulty of not knowing what happened. But, according to Danielle, they never really expected justice.

She said: “I mean, like, we knew how police saw Indigenous people, you know, Indian people, at the time.”

She added: “It was not a good experience ever to get pulled over or to stop, or to have the police come to your door.”

In 2017, family members, including Danielle and Debbie, testified about Laney’s death as part of Canada’s National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. As part of the process, they requested Laney’s case file and autopsy. Family members said officials repeatedly told them they couldn’t find it.

Months later, after Danielle said a coroner agreed to do a similar death search around the time of Laney’s death, they finally found it. It had been filed under a different name, which, Danielle said, she had never known her sister to go by.

“I know honest mistakes happen. But it raises suspicion, because they knew who she was. They knew who her family was,” said Danielle.

This is especially evident given that on the final page of the 14-page autopsy report and accompanying documents, her legal name was included.

Danielle said the family filed a complaint with Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Calgary Police related to Laney’s death within the last few years. An Alberta Royal Canadian Mounted Police spokesperson said they don’t have any other files related to Laney’s death.

A Calgary Police Service spokesperson said in an email: “Unfortunately, we don’t have any records of any CPS interactions with Ms. EWENIN, nor do we have a record of any complaints filed by her family. Without these details and important supporting facts, we are unable to comment on these allegations.”

During one part of the national hearings that was not broadcast publicly, Debbie said her family had the opportunity to speak directly to Royal Canadian Mounted Police officials and local police officers. Family members, according to her, told them they knew law enforcement was responsible for Laney’s death.

Debbie said she remembers an official responding: “Well, unfortunately, you know, we will never know.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance