Supercar legend Henrik Fisker has designs on a cheaper electric revolution

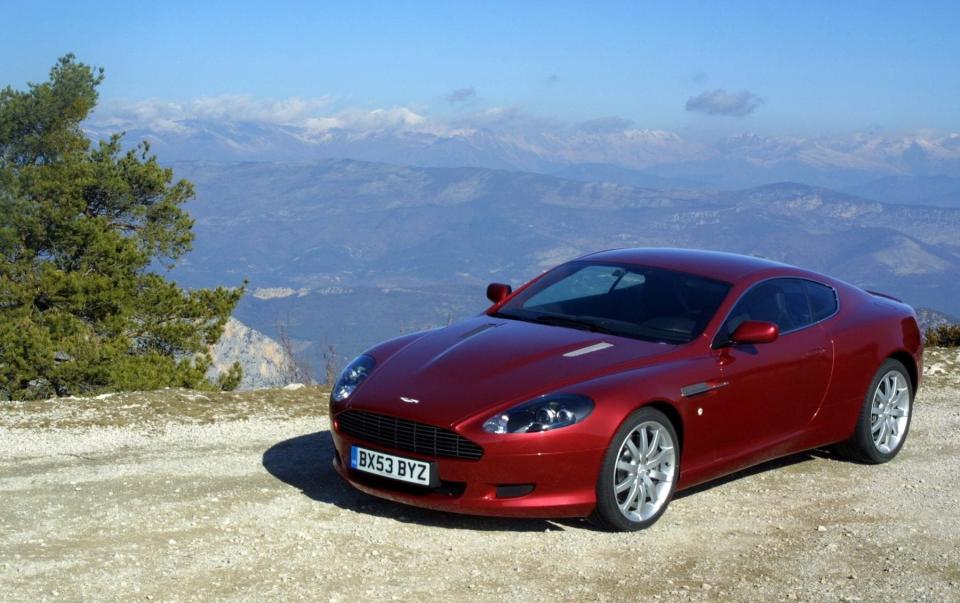

“If you look at the car, it fundamentally hasn’t changed much in the last 50 years,” says Henrik Fisker, who designed the Aston Martin DB9 alongside Ian Callum.

“It still has four doors, a trunk that you slam, it’s put on a truck and sent out to a dealer. We looked at that entire chain of events and said: ‘what if we start with a clean sheet of paper?’”

Fisker’s plan is simple: do what Apple did to the mobile phone market. The Danish-born veteran of BMW and Aston Martin came up with his business model for his synonymous automobile company after observing Apple topple Nokia as the biggest smartphone company in the world.

He watched as Apple designed its products before outsourcing the construction to other companies, in contrast to large car manufacturers that commonly own production plants, and decided to do the same.

In 2016, the entrepreneur founded California-based car maker Fisker, which aims to revolutionise the development of electric vehicles with new battery technology to meet challenges such as range and cost.

The 2023 Fisker Ocean SUV is due for deliveries in late 2022, but the chairman and chief executive plans for a lineup of four further vehicles by 2025.

Fisker will design the cars – responsible for the bodywork himself – and outsource the making of the motors to firms including Magna International, one of Canada’s largest companies, and Apple supplier Foxconn.

This will keep costs low, he argues – central to his vision. “Everybody seems to be launching super-luxurious electric vehicles, even the old or the traditional carmakers,” Fisker, 58, says from his base in Los Angeles.

He points to the recently launched Nissan Ariya electric SUV, which starts at £42,000. He compares it to Fisker’s original Ocean model, which he plans to sell for £34,990 with a range from 275 miles.

“I think the real market potential is in the high volume beyond the market of the wealthy, who have bought electric cars,” he adds.

Electric car sales in the UK have boomed this year, doubling their share to make up one in five new cars sold in Britain. But those backing a faster take-up point to the relative cost of most available cars, with electric versions being an average 25pc more expensive than combustion-drive motors.

There is concern that once the wealthy have bought their new toys, the rapid growth of electric takeup could slow.

But Fisker argues that making cheaper cars using his method could bridge the gap. In another cost-cutting measure, the company, which was co-founded by Fisker’s wife Geeta, who is also finance chief, has also shunned the dealership model.

While customers outside urban areas can go to look at the vehicle and book test drives at a much lower cost, he argues doing so in the city would spike costs.

“If we have a beautiful dealership in the middle of the city, and high real estate prices, guess who’s paying? That’s the consumer – and you are also paying for that free cup of cappuccino on that leather couch you are sitting on.”

He has also slashed options, rather than the endless customisability over the interior and exterior of some competitors. The Ocean will have three option packages. Naturally, the designer has added some unique design touches such as a rotating screen and California mode, where all windows and the sun roof open up for a semi-convertible feel.

There will also be no haggling with dealers, he says. “There’s just one price – just like with an iPhone.”

All of this is to allow him to make cars at speed, and pack in the latest technology.

“If you buy an electric car today, that technology was most likely chosen three years ago. When you buy our car next year, we’ve chosen this year,” which, Fisker says, means better batteries and longer ranges.

“I think one of the reasons it has not come up in the car industry [yet] is because it’s fundamentally an old dusty industry and they are stuck with thousands of manufacturing plants. You can’t just close them down and say we’re going to change the business model”.

This may cost household-name carmakers, with Fisker predicting new entrants like his will hold half the global car market share by 2030.

Whereas his parents’ generation would never dream of buying a car from a name outside a chosen few storied companies, now, he says “you see people running out buying vehicles that I barely even heard about”. That is, again, just like Apple, which never made phones until itdid and hoovered up the market.

In spite of his conviction, Fisker admits he has learned some tough lessons along the way. An early iteration of the company, Fisker Automotive, closed down in 2014 after seven years following the bankruptcy of its battery supplier. It was one of the world’s first producers of luxury hybrid electric vehicles.

His strategy has changed in the meantime: pick an established battery company (China’s Contemporary Amperex Tech), as opposed to a start-up, and raise all the money needed in one swoop, rather than going back to investors for seconds. “You need to raise a huge chunk of money- enough for your first vehicles,” he says.

An industry name, Fisker got his first big break working at BMW, where he designed the Z8 roadster, used as James Bond’s car in The World Is Not Enough.

“That’s really when I got noticed and people started calling me to hire me for other car companies,” leading him to a four-year stint at Aston Martin, where he oversaw the design of the DB9 and V8 Vantage, before going at it alone.

He estimates the company will need to sell about 20,000 cars per year to break even, and so has 22,000 Oceans ordered from customers.

Next on his design shopping list is the Fisker Pear, designed with big cities and a younger buyer in mind. The company aims to start pricing at £30,000. And finally, he has his eye on a sports car design, seen exclusively by The Telegraph, which will be developed in a high end division Fisker is setting up in the UK.

This is clearly where much of his passion lies: “The aim is that this should be the vehicle that could convince even the most diehard gasoline sports car enthusiasts that swear they will never drive an electric car. This car has to be so emotional, so sexy, so amazing, so attractive that you just, you just want it no matter what you think about electric cars.”

Fisker realises he has his work cut out, however. Supercar buyers want adrenaline and while the breath-taking acceleration of electric cars has surpassed that of most petrol models (the premium version of his Ocean will do 0-60mph in 3.6 second), they lack a danger buyers crave.

“That feeling that you are mastering a mechanical device that is very dangerous” is what he must recapture, he says. “That sense of achievement starts to get lost in electric cars because pretty much anybody can go in an electric car, slam the accelerator to the floor and accelerate just as fast as anybody else. And there’s really no accomplishment to that.”

He says: “When it comes to that sense of achievement, we have to find it somewhere else. What that is, we’ll keep it a secret for now, because I think that’s where part of the secret sauce is to regain that emotional connection with the driver.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance