On Swampy ground: a brief history of protest tunnelling in the UK

Protest tunnelling, back in the spotlight thanks to subterranean anti-HS2 demonstrations in London, became a national preoccupation in the 90s when environmental activists dug a complex series of tunnels in the path of an extension to the A30 in Fairmile, Devon, resisting attempts at eviction by police.

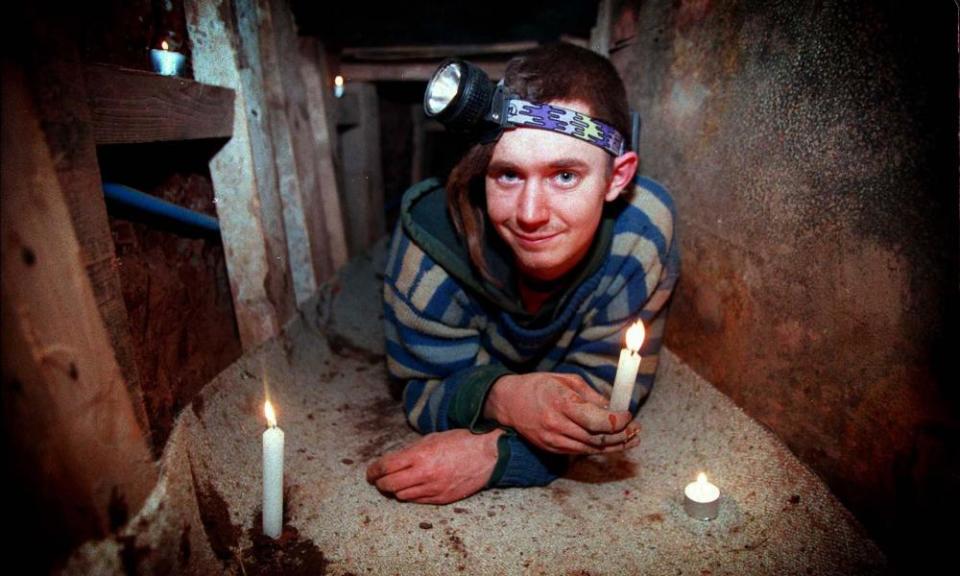

Swampy, the nickname of the well-known environmental activist Daniel Hooper, was one of a group of protesters demonstrating against rerouting the road, and spent seven days and nights in the tunnel. He was the last to emerge.

In 1996 the Newbury campaigners dug deep, and in March 1999 environmental protesters occupied a network of tunnels in protest against a planned leisure complex development in Crystal Palace. In 2013 activists again resorted to tunnelling as they tried to prevent the Bexhill-Hastings link road, which eventually opened in 2015.

Veteran activists who protested alongside Swampy in the 1990s say tunnelling is one of the most effective tactics protesters can use to thwart road or other transport building programmes, because it takes a long time to remove people from tunnels, costs a lot of money and can cause significant delays.

Related: HS2 protesters hope to occupy Euston tunnel for weeks

Ground encampments by activists are the easiest for bailiffs to clear, followed by treehouse protests. Tunnelling is the most difficult to deal with because it is skilled and delicate work to gain access to a tunnel and remove activists without causing a collapse and potentially risking lives.

According to the environmental activist tunnellers’ bible Disco Dave’s Tunnel Guide, the tactic was inspired by the Vietnam war-era tunnels at Củ Chi.

“At the end of the day it’s a money thing,” said one veteran environmental activist. “HS2 will be doing the maths and adding up the cost of police, security, delays to the building programme and the cost of specialists to remove the activists from the tunnel. There are six or seven anti-HS2 camps along the planned route of the high speed rail link. If all of those camps build tunnels the HS2 project could be in real trouble.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance