For those who have lost a loved one, Christmas is a time of grief as well as joy

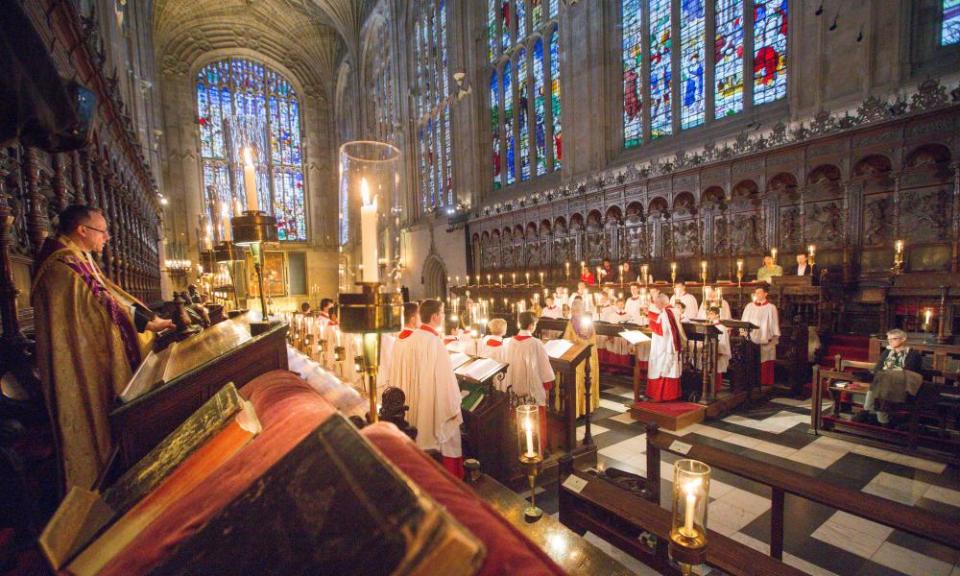

Every year on Christmas Eve, Carols from King’s is broadcast live on BBC Two at 5.30 in the afternoon. And every year, it begins in exactly the same way. Alone in the cavernous silence, the voice of the chosen choirboy, high and clear, climbs the three ascending notes that begin the first verse of Once in Royal David’s City. The sound echoes around the chapel and into homes all over the country, before the rest of the choir and the organ swallow up the soloist for the second verse. For many people, these three notes signify the start of Christmas proper, and the beginning of 48 hours of continuous and fanatical eating. For me, it signifies something else, too.

My primary school had a carol service at Christmas. Every year, someone from the year 6 leaving class would be picked to sing the solo in Once in Royal David’s City, which would open the service just as it does on television. There were only 20 children in my primary school class, of whom there were perhaps five who could sing, a number which included me and one of my best friends.

My friend and I had both watched older girls perform this sacred office in years gone by, felt their relief at coming through it without running out of breath or having their voice founder on the high notes, and we had heard the praise lavished on them afterwards. And so, naturally, we both wanted very badly to sing the solo ourselves when our year came around.

I knew, really, that it would be her; she was the better singer. But I still hoped that it would somehow be me. And so when she was chosen, I was happy for her, but also sulky and envious, like any precocious 10-year-old with the prospect of glory dangled in front of them.

When the evening came, she triumphed. In my mind, I see her walking down the aisle of the church. I can’t say now for a fact whether she sang while she walked or whether she sang before walking, but in my memory it’s happening at the same time. The only light is from candles, each child clutching one. All the heads of the people seated are turned towards her. I can only see her back from where I’m standing, itching with childish envy and trying not to drip wax on to my shoes. But I am happy, too, because my friend is singing beautifully and because, after all, it’s Christmas.

I would return to this church in 10 years’ time. It wouldn’t be Christmas, but the seasons’ other pole at the height of a hot summer, and I would walk down that same aisle to take my seat. The air would be still, but with a different stillness, and candles would be burning again. This time it would be my own small voice filling the church, thick with effort as I held the edges of the lectern. She would be there, too, and I would come into the church alone later to lay a hand on the box that held her, and to say what little could be said.

How can one suburban church be large enough to contain these two scenes, not to mention countless others of lesser importance that we shared? She and I trying to whip off each other’s clip-on pirate earrings backstage before a school play. My carrier bag of tins for the autumn harvest festival splitting, and us scrabbling for them between the pews. This is not just a problem with the inadequacies of this particular church, though. It’s a problem with my memories of her in general. How can I range across the joy of knowing her and the pain of her having died? How can I hope to reconcile these two extremes of feeling into something accessible?

It means so much to grow up with another person. After the solo verse, as Once in Royal David’s City goes on, it describes Jesus as being our “childhood’s pattern”. I never knew what that meant, and still don’t, really. But that phrase is attached for me now to her: she is woven inseparably into the pattern and fabric of those early years. Day by day like me she grew.

And it means so much to continue to grow up without someone. Happy places become sad ones, lives end, the years pass. I think that once you’ve lost someone you love, grief presses in at the window of all annual events. But there is something particular about Christmas. It’s a time to take stock. What is different, and what isn’t? Who is still here, and who is not? In this year of loss and separation, this will be more true than it has ever been. As well as for the celebration of new life, of love and of joy in togetherness, Christmas has always been a time for ghosts.

Each year I try to avoid Once in Royal David’s City. People understand if you cry about terrible things, but they’d prefer if it didn’t happen at Christmas and put everyone off their pudding. Or rather, I avoid Once in Royal David’s City in other people’s company. I do listen to it on my own. I thought that eventually it would lose its power, but so far it has not. And although it hurts to hear it, I am glad at the same time. Glad that there is music that has the power to evoke the memory of her so strongly. Glad that Christmas can be a time to remember her in. Glad that she was the one who got to sing the solo all those years ago, and that I got to watch her do it.

Imogen West-Knights writes for the Guardian, Vice and the New Statesman

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance