'Too big to fail': why even a historic ad boycott won’t change Facebook

On the evening of 13 July 2013, a few hours after George Zimmerman was acquitted over the fatal shooting of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, Alicia Garza logged on to her Facebook account and typed a phrase that would change the world: “#blacklivesmatter”. A few minutes later, she posted again: “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.”

That Facebook played a small role in the inception of a movement that may have become the largest in US history is the kind of story that the embattled company likes to point to when it makes its case that it does more good than harm. CEO Mark Zuckerberg boasted of the hashtag’s origin on Facebook in October 2019, when he delivered a speech about his view of free expression at Georgetown University.

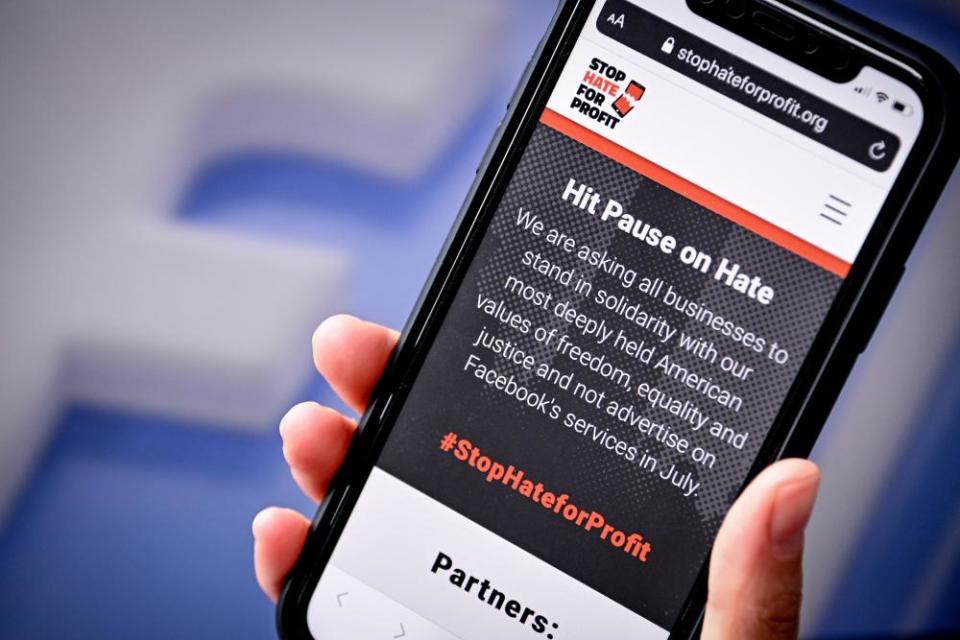

But however much credit Facebook thinks it deserves, the days of utopian thinking about the social media platform’s ability to foster positive social change are gone. On 8 July, the Black Lives Matter Global Network, an organization founded by Garza and two fellow activists, officially endorsed the Stop Hate for Profit boycott that has seen more than 1,000 companies forswear advertising on Facebook for at least the month of July in protest of its failure to combat hate speech. On the same day, a long-awaited civil rights audit excoriated Facebook for an inconsistent and often incoherent approach to protecting the bedrock values of an equal society, specifically citing that Georgetown speech as an ideological “turning point” with “devastating” effects.

The growing boycott and damning audit are just two expressions of a hardening consensus that Facebook is no agent of social progress, but rather an impediment to it. These criticisms are not just coming from leftwing activists or embittered competitors (a common dismissal of journalistic critique) but increasingly from Facebook’s own “community” of technologists, employees and former employees.

Still, despite the unprecedented nature of the ad boycott, it seems unlikely that Facebook will fundamentally change. The company has weathered seemingly existential crises in the past and managed to emerge with its leadership team, market capitalization, and business model intact. “This is not yet the straw to break the camel’s back,” said Dipanjan Chatterjee, vice-president and principal analyst for Forrester Research.

“Facebook is too big to fail.”

A company with ‘quasi-sovereign power’

In 2017, as Facebook came to grips with the fact that it was being blamed for the election of Donald Trump, the company debuted a new mission statement: to “build community and bring the world closer together”. This summer, Facebook did just that, bringing together a diverse and unprecedented coalition of non-profit organizations and massive for-profit corporations in opposition to itself.

The precipitating event for the Stop Hate for Profit campaign was Zuckerberg’s decision to allow Trump to quote a racist 1960s police chief’s threat against the hundreds of thousands of people who took to the streets to protest the alleged police murder of George Floyd: “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

Trump’s statement was widely read as having the potential to incite vigilante violence. The traditional media contextualized it with explanations of its historical resonance. Twitter hid it behind a warning label and prevented users from amplifying it. Facebook left it alone, with Zuckerberg reiterating his belief that “we should enable as much expression as possible unless it will cause imminent risk of specific harms or dangers spelled out in clear policies”. By dint of Trump’s position in government, Zuckerberg argued, the statement was not incitement but “a warning about state action”, and warnings of state action were allowed under Facebook policies, though that policy had never been “spelled out” before.

Related: Facebook decisions led to serious setbacks for civil rights – report

Zuckerberg’s reasoning was met with stunned disbelief by US civil rights leaders, as well as experts and advocates in free expression. That he would privilege the right of the most powerful person in the US to threaten violence against civilians over the right of those civilians to exercise their right to dissent remains a fundamental contradiction in Zuckerberg’s conception of free speech, one that operates in tandem with the company’s decision, announced by the company executive Nick Clegg in September 2019, to exempt the speech of politicians from its own third-party fact checking program.

This inclination to privilege Trump’s speech over others has continued with the company’s bizarre refusal to enforce its well-intentioned rules banning voter suppression against a president who is unambiguously using the platform to attempt to suppress the vote.

“Elevating free expression is a good thing, but it should apply to everyone,” the civil rights auditors wrote in reference to these policies. “When it means that powerful politicians do not have to abide by the same rules that everyone else does, a hierarchy of speech is created that privileges certain voices over less powerful voices … Mark Zuckerberg’s speech and Nick Clegg’s announcements deeply impacted our civil rights work and added new challenges to reining in voter suppression.”

The auditors also drew special attention to Facebook’s poor track record on identifying and banning hate groups. Until March 2019, Facebook argued that white separatism and white nationalism were distinct and less dangerous than white supremacy. Though Facebook reversed that policy, the auditors appeared frustrated that the company continues to define white nationalism too narrowly – and has ignored their suggestions for improvement in this area.

Facebook’s chief operating officer, Sheryl Sandberg, who led the company’s participation in the audit, said that the “two-year journey has had a profound effect on our culture and the way we think about our impact on the world”, adding: “It has helped us learn a lot about what we could do better, and we have put many recommendations from the auditors and the wider civil rights community into practice. While we won’t be making every change they call for, we will put more of their proposals into practice soon.”

Sandberg and other executives have also defended the company against criticism of its efforts on hate speech, arguing that they invest heavily in systems to remove hate and catch 89% of hate speech before it is reported. (“Ford Motor Company cannot say 89% of its fleet has seatbelts that work and still sell them,” said Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the Anti-Defamation League.)

Whether Facebook will ever hit upon a more coherent approach to protecting the free expression of the powerless as well as the powerful depends on whether it ever comes to grip with its own role as the largest censor in the history of the world.

“Facebook is governing human expression more than any government does or ever has,” said Susan Benesch, a faculty associate at Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society. “They have taken on the task of defining hate speech and other unacceptable speech, which is a quasi-sovereign power … and we the public have no opportunity to contribute to the decision-making, as would be the case if the decisions were being made by a government.”

Indeed, despite company executives’ paying lip service to the concept of democracy from time to time, Facebook is structurally monarchical, thanks to Zuckerberg’s majority control of the company’s voting shares. Asked to describe the company’s decision-making process when it comes to Trump’s posts on a recent conference call with reporters, Clegg sounded less like a former deputy prime minister and more like a royal courtier when he explained: “For the most difficult decisions, there’s one ultimate decision maker, our CEO and chair and founder, Mark Zuckerberg.”

Change from the bottom up

One of Zuckerberg’s few concessions to criticism of his power has been the establishment of an “oversight board”, which will eventually be empowered to overrule him on certain decisions related to content takedowns. But the group appears to be in no hurry to step into the debate over Facebook’s handling of Trump, at least not before the November election. On 7 July, it responded to calls for its intervention with a statement that it “won’t be operational until late Fall”.

Related: 'Disappointing' Zuckerberg meeting fails to yield results, say Facebook boycott organizers

Meanwhile, Facebook’s stock price has already recovered from the hit it took when Unilever joined the ad boycott, suggesting that despite its success in generating headlines, the campaign is unlikely to have a lasting financial impact. “For some of the marketers that have joined the boycott, it is possible they were intending to pull back anyway for pandemic-related reasons,” said Debra Aho Williamson, principal social media analyst for eMarketer. “In addition, we believe that other advertisers will actually increase their spending on Facebook in July, taking advantage of potentially lower ad prices in certain categories where advertisers have pulled out.”

Chatterjee, the Forrester analyst, concurred. “If you choose to be cynical, it is easy to see how a story about budget-crunched media cuts can easily be purpose-washed into a stand on social justice,” he said.

Chatterjee also pointed out that even as Facebook endures a “tongue-lashing in the US”, it continues to consolidate and expand its power abroad, such as through its $5.7bn deal with Jio Platforms in India, an investment that he expects will give it “unprecedented access to Indian consumers”. “#StopHateForProfit is a big deal in the context of US sentiment, but for Facebook there are also other big fish to fry,” he said.

To the University of Virginia media studies professor Siva Vaidhyanathan, campaigners against Facebook need to come to grips with the global nature of its threat.

“One of the most frustrating things about the rise of Facebook criticism in the past three years has been its relentless focus on Donald Trump and the United States of America,” he said. “The US got off easy in 2016 – the same year that Rodrigo Duterte took over the Philippines by riding Facebook to victory, and two years after Narendra Modi took over India by riding Facebook to victory. Much of the world suffers from all of the Facebook maladies much worse than the US.”

Vaidhyanathan argued that solutions to Facebook’s ills cannot be achieved with oversight from above but will require a more fundamental shift from below.

“We have the potential to imagine radical interventions, and they have to be radical – they have to get to the root of Facebook,” he said. “The root of Facebook is the fact that it is a global intrusive surveillance system that leverages all that behavioral data to target both ads and non-ad content at us.

“Go for the root. If you can sever that, you pretty much destroy Facebook. It’s just a website at that point, and that would be lovely.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance