Why it’s not worth working hard in Tory Britain

On paper, Jack Drury is just the sort of high-achiever the Tories should be bending over backwards to help.

By the time he was in his mid-20s, Mr Drury, a “church-going grammar school boy from Birmingham”, was already earning more than £100,000 from a flourishing career in tech.

“When I was growing up, we didn’t have loads of money,” he says. “£100,000 was what you earned if you won The Apprentice.”

An exceptional academic record and five years of hard graft seemed to have paid off. But the reality of life as a high-earner came as a shock: he calculated that for every extra £1 he was earning, the taxman was taking 71p.

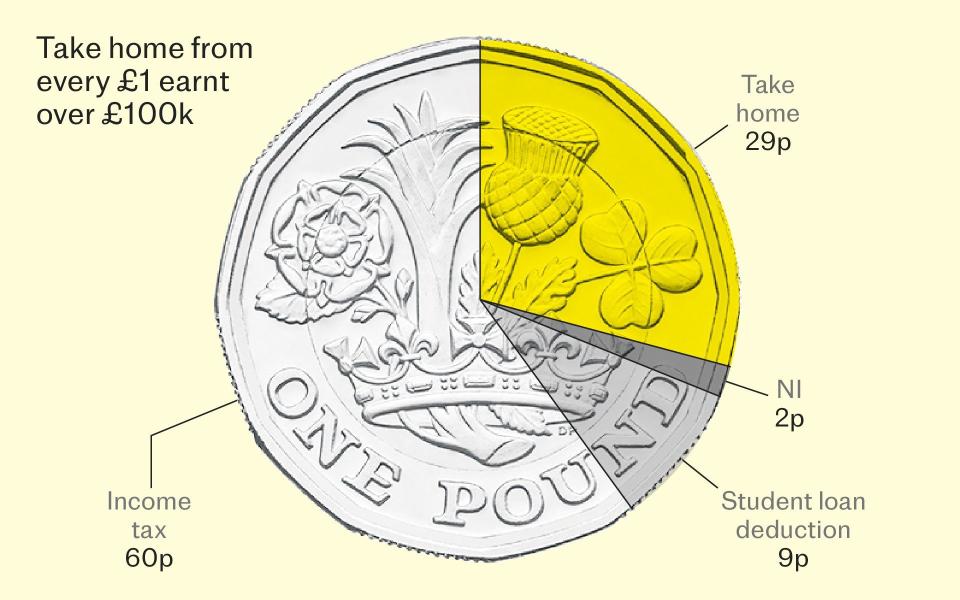

“I didn’t appreciate that you could earn that much but still not feel that rich, and that when I crossed that magic line [of £100,000] I was only getting 29p in the pound. It was extremely depressing.”

Mr Drury had tipped into the £100,000 tax trap, when the 40pc higher income tax rate combines with the tapered loss of the personal allowance – the amount you can earn tax-free. Coupled with student loan repayments clawing back 9p of every extra £1, and National Insurance (NI) contributions shaving off another 2p, Mr Drury saw his earnings evaporate.

The experience has dented his drive to get on to the next rung of the ladder.

“My friends and I actively talk about gaming our incomes through pensions or charitable giving.

“Loads of people I know have chosen to settle in the high £90,000s. They are choosing to earn less. It’s brutal.

“I don’t feel flush. All the money I could earn above £100,000 I don’t care about earning – it doesn’t make me feel any better off or more secure.”

Now aged 28, he has bought a home in rural Hertfordshire with his fiancée, Anna, and earns £128,000 working in HR at a venture capital-backed software company, pushing him into the 45p additional rate tax bracket.

He has chosen to funnel all his income over £100,000 into his pension to avoid being hit with high tax rates. But he wonders how this is benefiting the British economy, as 95pc of his pension pot is invested abroad.

“I’m in a situation where I’m choosing not to earn this money so the taxman can’t take loads of it, so I’m putting it in my pension. But it’s going to Japan [in stocks], despite the big hoo-ha in the Budget about investing in Britain. It’s just mad.”

Why work?

Mr Drury isn’t alone. Graduates, parents, high-earners and benefits claimants are all caught in a tax system that skews incentives and discourages hard work.

Income tax thresholds have been frozen since 2021, dragging millions of workers into higher brackets. By the end of this Parliament, Britain’s middle- and high-income households will have experienced the largest setback to living standards since records began in 1961, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has warned.

Punishing tax rates mean ambitious workers may decide that there’s no point getting ahead. If enough taxpayers reach that conclusion, the consequences for the economy will be severe.

Britain is already grappling with an alarming rise in economic inactivity. Nearly 3 million under-25s are neither employed nor looking for a job, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), while 9.3 million people of working age are now economically inactive – 700,000 more than before the pandemic.

Bill Dodwell, of Deloitte, and formerly the head of the now disbanded Office for Tax Simplification, believes tax traps and cliff edges inevitably dampen growth.

“People who could work more and would like to work more are being prevented from doing so by these barriers,” he says. “It’s certain that some people are turning down promotions or cutting down their hours.”

Others are leaving the workforce altogether.

Nigel Elliot, 67, chose to retire when he worked out that drawing his pension would leave him better off than earning a salary.

He had worked for Exxon Mobil for 35 years, rising through the ranks to become a senior fuels adviser for Europe. The job was well-paid but gruelling.

“I was out most weeks,” he says. “Either in Brussels or globe-trotting around the world. I would take calls 24/7 if something went wrong anywhere in the world. I’ve been called on Christmas Day before.”

His plan had always been to retire at 60. But after tipping into the £100,000 tax trap he decided to call it quits four years early.

“I loved my job and would have continued. But in my last year of working, my gross salary was £118,000 and I paid £45,000 in income tax and NI. It’s ridiculous. It disincentivises hard work.

“There’s absolutely no reason to keep busting a gut if that’s going to happen. Many of my colleagues made the same calculations. We said ‘this is crazy, we’re being punished every which way’.”

By the time he was 56, he was taking home £4,943 a month.

“I looked at my pension prediction, which was £3,000 a month. I was paying the mortgage at £1,850 a month, with not much left to pay off.

“So I decided if I pay off the last £40,000 with part of my lump sum when I retire, in terms of cash to spend I’m going to be about equal – and don’t have to work.”

He is now happily retired, spending his time “hill-climbing”, a form of motor racing in which cars compete on an uphill course. He helps out the Federation of Historic Vehicles with any fuel queries, and enjoys doing DIY around the house.

But if Mr Elliot is viewed purely as a cog in Britain’s economic machine, his decision to retire early is bad news – one more highly-skilled worker out of the workforce.

“The taxman lost four years of £45,000 a year,” he says. “This year they’re only going to get £12,000 off me.”

It’s not just high earners being put off working. A recent report by the Tax Law Review Committee (TLRC) shows that some of Britain’s lowest earners are also facing tax rates of almost 70p on every extra £1 of income earned, keeping many stuck in part-time jobs.

One reason is Universal Credit (UC), a benefit that varies depending on age, number of children, disability, savings and how much a claimant works.

The TLRC’s report uses the example of “Deirdre”, who is employed part-time and earns £12,570 a year, meaning she pays no income tax or NI. She claims £800 a year in UC.

If Deirdre were to increase her hours to earn an extra £1,000 a year, £200 would be taken in income tax, £120 in National Insurance, and she would lose £374 of her UC.

It means her decision to work more would leave her with just £306 out of the additional £1,000 a year.

Mr Dodwell, who co-authored the report, says: “There are all sorts of examples of Universal Credit being withdrawn as you go over certain income levels – that’s definitely a disincentive to work for lots of people.”

‘It feels like the tax man is breathing down your neck from cradle to grave’

The seeds of today’s punitive tax regime can be traced back to the last Labour government.

In the wake of the financial crisis, then-chancellor Alistair Darling introduced a new 50p income tax band for those earning over £150,000, later cut to 45p by George Osborne in 2012.

Mr Darling also hit higher earners with a personal allowance taper, meaning that once someone’s salary hits £100,000 they start to lose their £12,570 of tax-free income at a rate of £1 for every £2 earned, until it disappears at £125,140.

Between 1997-98 and 2010-11, when Labour was in power, the tax paid on earnings of the average household rose by between £600 and £1,895 in real terms, according to estimates by the House of Commons Library and the IFS. This was in part due to rising incomes during the period.

But Britain’s tax burden has been turbo-charged under the Tories. When Boris Johnson came to power in 2019, Britain could still consider itself a low-tax economy, relative to other developed countries. Its tax rate is now above the OECD average.

Over the last Parliament, tax revenues as a percentage of GDP will have grown from 33pc to 37pc – the highest level since the 1940s. The rise has been fuelled by a stealth tax raid which has dragged millions of taxpayers into higher tax brackets as inflation pushes up wages.

Income tax thresholds will remain frozen until 2027-28. Jeremy Hunt went one step further in April last year and cut the additional rate threshold from £150,000 to £125,140.

The result is that modest earners are now being taxed “as if they were rich”, according to the TaxPayers’ Alliance campaign group. Just 3.5pc of British adults paid the 40p rate in 1991, IFS figures show. This is set to climb to 14pc by 2027.

In 2023-24, 18pc of income taxpayers are projected to pay either the higher or additional rate, up from 10.4pc in 2010, according to Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) data.

Many Conservative MPs are unhappy with the country’s punishing tax regime. John Redwood MP, a member of the Conservative Growth Group, says the demotivating effect of higher taxes is being underestimated.

“High taxes penalise work and enterprise. The very rich just leave the country taking their incomes and investments with them. People who have worked hard and get promoted get caught in the higher tax traps, losing too much of the extra money they could earn.

“The OBR and Treasury never allow enough in their models for the energising effects of lower tax rates and the deep damage done by higher rates sapping effort, undermining enterprise and putting people off doing more.”

Ranil Jayawardena MP, a former cabinet minister and chairman of the group, thinks the current tax regime goes against the grain of Conservatism. “It feels like the tax man is breathing down your neck from cradle to grave. As Conservatives, I believe we should reward people who are trying to do the right thing.

“It’s time for tax reform for every stage in people’s lives – for first-time buyers, for homeowners, for couples and working-age parents with children, for entrepreneurs – and for those that have worked their whole lives to hand something down to their loved ones.”

The argument that higher taxes distort incentives is nothing new. But the interaction of taxes, regulations and benefits – built-up like layers of sediment over decades – makes Britain’s tax system particularly dysfunctional.

Sam Ray-Chaudhuri, an economist at the IFS, believes elements of the country’s tax system often work against each other. “Any tax is going to have a disincentive effect,” he says. “Taxes introduce distortions. But it’s much worse and more obviously perverse to have very high marginal tax rates.

“It’s why simplification seems a better goal than raising taxes or introducing new ones, and something more obviously desirable – to arrive at a system without these irregularities in it.”

Punishing parents

One of the biggest distortions occurs once a parent earns more than £100,000.

At this point they lose their entitlement to free childcare, worth up to £14,500 a year for someone with two children. They also hit the 60pc marginal rate because of the personal allowance taper and 40pc higher tax rate. This creates a strange incentive for parents earning £99,000 to turn down a pay rise so they can hold on to the government benefit.

A parent paying average London rates for 50 hours of childcare a week would be worse off earning £144,000 than a parent in the same position earning £99,000, the IFS found. By working fewer days, parents not only dodge the tax trap but also cut their childcare costs, which currently average at £285 per week full-time, or £13,695 a year.

The TLRC has warned that parents face “insurmountable barriers” to work once they earn more than £100,000, forcing them to cut back working hours to keep hold of childcare perks.

“John”, who preferred to remain anonymous, decided to drop down to three-and-a-half days a week to avoid the childcare cliff-edge.

As the sole earner in his household, and with three children under six, he felt he had no other choice but to reduce his hours.

He says: “I’m an additional rate taxpayer but I’ve made sure to cut my income down to £95,000. No other option makes sense, as we live in London and childcare costs are through the roof.

“I should be encouraged to make money, pay a fair rate of tax and contribute to the economy. Instead I’m being painted into a corner by this ludicrous cliff-edge. All that’s going to happen is that skilled workers are going to cut down their hours or flee abroad.”

Experts have warned that the cliff-edge is holding back Britain’s economy by encouraging parents to shun work.

Ian Cook, a wealth adviser at wealth manager Quilter, says: “It’s causing confusion with a lot of parents. It’s damaging productivity and almost certainly holding back the economy.

“A parent on £100,000 is being punished three times – no free childcare, the removal of the personal allowance and 40p income tax on top. It’s only at quite a lot above £125,000 when there’s more of an incentive to push on. Those who can earn more are reluctant to do so.”

Squeezing education

The childcare trap is weighing on Mr Drury’s mind.

“If I had children I’d game my income, no question,” he says. “I might drop down to four days [a week].

“I have friends doing this already. One of them with two kids was earning £130,000 said it wasn’t worth it. He’s now dropped down below £100,000 so he can get free childcare. It’s ludicrous, but that’s what he’s done.”

Yet despite his £128,000 salary, Mr Drury is unsure about whether he can support a bigger family.

“I’m not sure I can afford children. Dexter, my dog, is expensive enough.”

He believes the “absurd” student loan system has a lot to answer for.

Graduates saddled with debt are one of the groups with the highest marginal tax rate in Britain. Those with “Plan 2” student loans – who started university between 2012 and 2023 – must pay their debt at a rate of 9pc on everything they earn over £27,295.

It means graduates with an income between £27,295 and £50,270 face a marginal tax rate of 55pc – once income tax, NI contributions, student loan repayments and pension contributions were factored in.

Those who did a master’s degree, and took out a student loan to pay for that too, must pay 6pc of all income over £21,000 – meaning many middle-earners are sending 60p of every additional pound they earn to the taxman.

For higher earners it can be far worse. An extreme example is of a graduate with student loans earning £124,150 who receives a £1,000 pay rise, who would keep only £6.50 – an effective tax rate of 99pc.

This is due to the loss of the personal allowance as well and the 45pc tax rate, and also assumes they have £500 in savings which is then taxed at the 45pc rate.

Stuart Adam, of the IFS, says: “For those who are not going to pay off their student loan, it effectively acts as a tax.

“It’s a much smaller effect than the withdrawal of means-tested benefits or the £100,000 cliff-edge. But to the extent it acts like a higher income tax […] it discourages promotion, overtime, higher paid jobs and you could make the case it encourages tax planning and avoidance.”

For younger graduates, hit with harsher terms to pay back their student debt under “Plan 5”, the sting of this loan that behaves like a tax will be even sharper.

Mr Drury says: “In the strict terms of this game, you could argue the winners are the ones who earn under £27,000 who get their education for free.

“The runners up are people like me who earn too much too soon – it means I will have paid it off before compound interest really gets going.

“But everyone else will pay that 9pc for the full 30 years, or the vast majority. If there’s any gap in which you don’t earn a lot at the start of your career – like doctors and nurses in training – the interest just compounds. It’s absurd.”

The threat of Labour

If a Labour government is elected this year, it looks unlikely that rebalancing the scales in favour of aspiration will be a priority.

Last year, Jeremy Hunt scrapped the lifetime allowance (LTA) – the £1.073m cap on how much someone can save in total in their pension without incurring a tax charge of up to 55pc.

The aim was to stop highly paid doctors from retiring as the NHS grapples with a recruitment and retention crisis. The number of hospital doctors retiring early rose from 178 in 2008 to 557 in 2023, while the number of GPs doing so rose from 198 to 867 over the same period, British Medical Journal data shows.

But Labour has vowed to reintroduce the LTA if elected, and backtracked on plans to exempt certain public sector pension schemes from the cap.

On education, too, Labour appears to be planning to undermine incentives to aim high. One of its flagship policies is removing the VAT exemption from independent schools, meaning most will be forced to pass on a 20pc fee rise to parents.

According to the Independent Schools Council, the proposed tax raid risks forcing out a fifth of pupils – 40,000 – after a survey of parents found 20pc would “definitely” withdraw their children, piling pressure on the state sector.

Headmasters have warned that private schools will be forced to cut scholarships and bursaries for the poorest as a direct result of the plans.

Silas Edmonds, headmaster of Ewell Castle School in Surrey, says: “It is those families who can just about afford [the fees] – aspirational working-class and lower-middle-class backgrounds – who will leave and seek out state school places.”

Mr Cook, whose son attends a “modestly priced” private school in Hampshire, says Labour’s plans would price him out.

“I wouldn’t have chosen to send him to private school if I had known VAT would have gone up by 20pc. It’s one of the most horrible taxes.”

As a single parent from a working class background, he wanted to give his son better opportunities than he had had.

“Winchester [College] always gets dragged into the conversation. For these parents, paying 20pc more won’t make a difference. There aren’t Lamborghinis and Ferraris parked outside my son’s school.

“But for the truly aspirational parents, those right at the edge of being able to afford to give their kids better odds than they did, it’ll be absolutely devastating.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance