Twisted Locks of Hair: The Complicated History of Dreadlocks

Hair is not just hair, it speaks to our personalities, our communities, and our histories. In some societies hair can represent spiritual connections, whilst different styles can indicate specific rites of passage.

Last year I started the Instagram account @in.hair.itance, to celebrate the diversity of hair in non-white cultures across the globe. When I posted a photograph of a Native American man with dreadlocks, I was surprised to see the amount of attention it garnered. It quickly became my most liked post and created quite a conversation in the comments section.

“I just wish people would stop complaining about hair!” writes a white lady with electric blue locks. “It’s HAIR”, she continues, “do what you want with it no matter what race you are!”. Her comments are consistent with what is known as colour-blind racism. This ideology is based on the assertion that racial privilege does not exist. Unfortunately, not only is this simply untrue, it is also dangerous. It minimises structural racism and ignores issues of under-representation of people of colour. The comments made by this lady (who goes on to report Italian, German, and Scottish ancestry) reek of white privilege. The societal advantage that her skin colour affords means that being told that a decision that she had made could be offensive to other people, seems outrageous to her. This colour-blind, post-racial narrative attempts to erase the diversity and cultural legacy that my page is trying to highlight.

I started my page to provide a space for people of colour to celebrate who we were prior to colonisation and the cultural brainwashing that established euro-centric beauty as the standard. The response has been immense. I receive dozens of messages a day from people expressing their love for the page and thanking me for creating it. We have been written out of history, but @in.hair.itance puts us front and centre. My page provides a springboard for people of colour to engage meaningfully with their history and reflect on its impact today. Comments like those mentioned earlier are not isolated and further reinforce the role of education as a tool to dismantle racism at its base. The history of dreadlocks, understandably, is complex.

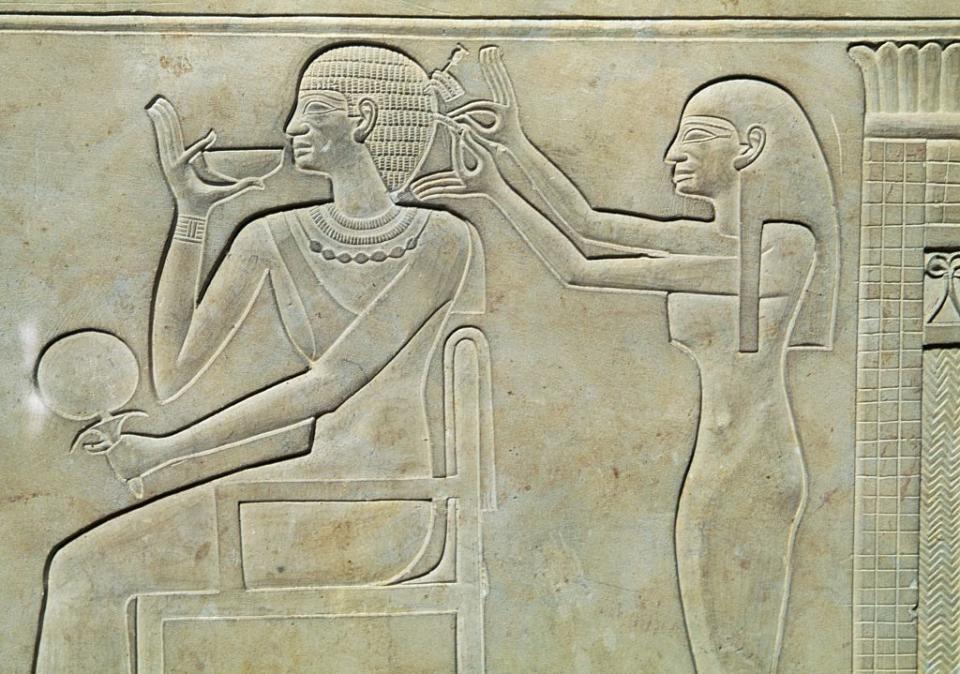

The earliest written reference of locks is found in Vedic scriptures, holy Hindu texts dating back to 1500BC, in which Lord Shiva’s hair is referred to as ‘jata’, a sanskrit word meaning “twisted locks of hair”. In almost all visual depictions of Lord Shiva, he is seen with locks of hair flowing past his shoulders or tied above his head in what is called, ‘jatamukuta’ (crown of matted hair). For devotees, Shiva’s hair is of such importance that the sacred river Ganges is believed to flow from his matted locks. The earliest archaeological evidence of locks is found in the mummified remains of Ancient Egyptians as well as from the pre-Colombian Incan civilisation in Peru.

In some cultures, especially in South Asia and the Middle East, allowing uncombed hair to form into matted locks is a symbol of the rejection of materialism and vanity. In India, these religious ascetics with locks are referred to as ‘sadhus’. In other cultures, locked hair is symbolic of a spiritual connection to a higher power. For example in Ghana, the Akan people refer to locks as ‘Mpɛsɛ’, and they are usually reserved for priests of Akomfo. Similarly, in Mexico, the Spanish recorded the fact that the Aztec priests had their hair untouched, long, and matted.

In many parts of Africa, locks are associated with strength and only worn by warriors. For example, warriors of the Fula and Wolof people of West Africa and the Maasai and Kikuyu tribes of Kenya, are all known for locked hair. Interestingly, in Nigeria, among both the Yoruba and Igbo people, locked hair is viewed with suspicion when worn by adults. Although when children are born with naturally matted hair, they are referred to as ‘Dada’' and viewed as spiritual beings. They are celebrated as bringers of wealth and only their mothers are allowed to touch their hair.

Although dreadlocks have been worn continuously by people of colour in Africa, Asia, and the Americas from ancient times until now, their popularisation in the West only occurred in the Seventies. This was due to the success of Jamaican-born reggae artist Bob Marley following his conversion to Rastafarianism.

The origin of dreadlocks within the Rastafari tradition is a topic of much debate. Leonard Howell, hailed as the first Rasta, was known to have links with Indo-Jamaican followers of Hinduism and even had a Hindu-inspired alias ‘Gong Guru Maragh’. This has led many to believe that dreadlocks and the smoking of cannabis (note: ‘ganja’ is a Hindi word) was inspired by traditions brought to Jamaica by Indian indentured labourers. Others say that Rastas were inspired by the locks worn by warriors of the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya during the Fifties.

Although Leonard Howell wore his hair short, it is said that his guardsmen at the Pinnacle Commune wore locks as a way to portray strength and instil fear. Another tradition places the origin of dreadlocks with the House of Youth Black Faith (HYBF), a group of radical young Rastas who formed in the late Forties. They grew their hair into locks as an affront to Jamaican society and to mark their separation from the mainstream. Soon, dreadlocks had become such a contentious issue that the House split into two groups, the “House of Dreadlocks” and the “House of the Combsomes”. Eventually the latter was dissolved and dreadlocks became the well known symbol of Rastafari that it is today.

One source states that original Rastas called their locks ‘zatavi’ (from the Hindi ‘jata’) as it appears the word “dreadlocks” was not coined until 1959, when a group of Rasta friends met in their yard. The word ‘fear-locks’ was apparently proposed but quickly dismissed. The reasoning for using the word is related to both a dread or fear of God, as well as the feeling that the locks would scare off potential threats. Whatever their initial origin, it is without debate that dreadlocks in the modern-day are synonymous with Rastafarianism.

However for Rastas, dreadlocks are much more than just a hairstyle. They represent a connection to Africa and a rejection of the West, which they term Babylon. Dreadlocks represent a renewed sense of pride in African physical characteristics and Blackness, which ties in with their belief about keeping things natural. There is also a deeper spiritual connection as dreadlocks are believed to connect wearers to Jah (God) and “earth-force”, his mystical power which is found throughout the universe. Some even believe that the knotting or locking of hair keeps this power in the body, preventing it from escaping through the head. This belief in dreadlocks holding physical power is attested to in the Biblical story of Samson who lost his strength when Delilah cut his seven locks. The Nazirite vow followed by Samson, in which alcohol is avoided and hair is not cut, is described in the Book of Numbers in the Bible and was adopted by Rastafarians as a central tenet of their belief system.

I cannot exclude the possibility of locked or matted hair being found in European history at some point in time. There is certainly visual evidence of Ancient Greeks with braided hair and possibly locks, however one could argue that the Greeks were much more influenced by their darker skinned Eastern and Mediterranean neighbours, than they were their Northern ones. Despite this possibility, it should be without argument that the modern-day wearing of dreadlocks by white people is unconnected to their own history and instead inspired by ours. When I have asked white people about their dreadlocks, I have had responses which vary from, “My hair would do this naturally if I didn’t comb it”, to “Vikings had dreadlocks”. I have looked into this latter statement and can find no evidence to suggest that this is true. There is a Roman reference, credited to Julius Caesar, in which the Celts are described as having “hair like snakes”. However it seems nonsensical to suggest this constitutes evidence of the existence of dreadlocks in the early part of the first millennium, let alone using this as the reason why you may wear dreadlocks today.

This erasure of the cultural impact of reggae music, Bob Marley, and Rastafarianism is what makes this cultural appropriation. In the simplest language, cultural appropriation happens when a dominant culture takes something from an oppressed culture without any acknowledgment of where it has come from. This can be problematic for a number of reasons. Firstly, it ignores the inequalities that exist in society, leaving it up to people of colour to “call out” what we see as injustices. In the process we are labelled as oversensitive, while centuries of our history are erased before our eyes. It feeds into Euro-centric beauty standards.

Hair that is viewed as unprofessional on a Black person becomes fashionable when worn by a white counterpart. Once again the dominant culture is benefitting while minorities are further marginalised. A perfect example of this is Justin Bieber. He has made a career out of the cultural appropriation of Black music. It was therefore not surprising when he attended an awards show a few years ago with faux locks. Despite this he is still one of the world’s best-selling music artists. By contrast, mixed race actress and singer Zendaya (of former Disney fame) was glowing when she wore dreadlocks to the Oscars, only to be torn down by TV host Giuliana Rancic, who commented that she looked like she “smells like patchouli oil and weed”.

When people say “hair is just hair” they are overlooking the existence of systemic inequalities. Only last year the State of California brought about a law, known as the Crown Act, to ban workplace or school discrimination based on one’s natural hair. This month marks a year since the act was signed, and whilst the Covid-19 pandemic and social distancing have impacted on celebrations, virtual events are ongoing and there are plans to commemorate the event annually to bring greater attention to the subject. Hair is intimately linked to our history and our identities today. This shouldn’t be difficult for people to understand. Just look at the predominantly white US protests over the inability to get professional haircuts during lockdown.

Hair discrimination is as much of an issue for people of colour in this country. In the Fifties and Sixties, when immigrants came to the UK from former colonies in the Caribbean, Africa and Asia, they faced discrimination not just because of the colour of their skin. Hair was a hot topic. Afro hair was untidy and unprofessional, while dreadlocks were labelled as unclean. Sikh men were unable to find work unless they removed their turbans and cut their hair. These issues have not disappeared. There have been multiple cases of Black students being sent home from school for haircuts deemed as “extreme” or against uniform policy. One 12-year-old boy, Chikayzea Flanders, who was brought up in a family of Rastafarians, was even told that he would be suspended from school unless he cut off his dreadlocks.

This cultural brainwashing, which is very much a British export, has even resulted in a case reported last month in which Jamaica's Supreme Court ruled that a school was justified in banning a child with dreadlocks for reasons of "hygiene". Irish-Nigerian academic, Emma Dabiri, wrote a book just last year called “Don’t Touch My Hair” in which she details the issues she faced growing up in Dublin and learning to love and accept her own hair. She recently created a petition (with more than 50,000 supporters) asking the British Government to amend the Equality Act to include hair as a protected characteristic.

With the Black Lives Matter movement continuing to gain momentum, people are beginning to look at their own internal prejudices as well as the systems which allow racism to continue. People are highlighting the importance of being actively anti-racist and addressing inequalities. This should include accountability for actions which disadvantage and disempower already marginalised groups. The cultural appropriation of hairstyles which have a complex and meaningful history is integral to this. Being ignorant to these issues, when we live in an age of information at our fingertips, is not acceptable. We need to ensure that differences between cultural groups are not only celebrated but also respected.

Kyle Ring is a London-based doctor and the founder of @in.hair.itance, who is currently studying for a masters in postcolonial studies.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance