Why India is bankrolling the UK’s high-risk OneWeb ambitions

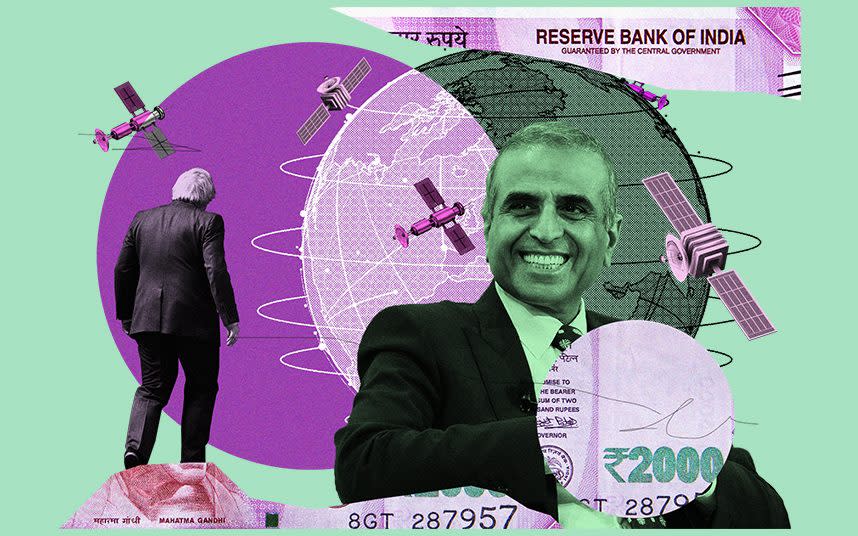

In 1976, fresh from graduating from Punjab University, Sunil Bharti Mittal borrowed $1,500 (£1,200) from his father to start his career making bicycle crankshafts.

Four decades later, he is the owner of a sprawling conglomerate spanning telecoms, financial technology and real estate, with a personal net worth of more than $11bn.

As of June, he is also the man whose hands share the tiller of Britain's latest national venture into space.

On Friday, the Telegraph revealed that a consortium comprising Mittal's Bharti Enterprises and the UK Government had outbid their rivals to take possession of OneWeb, a bankrupt satellite company headquartered in London, in one of Britain’s biggest private sector deals since the last crash.

The 11th-hour deal gives both the UK and Bharti a 45pc stake for $500m each, while the other 10pc remains with existing investors.

As well as giving both the UK and India a hand in delivering a system that could connect billions of people to high speed internet from space, the deal could also see a new common interest forged at a time when Britain is on the hunt for economic partners post-Brexit.

“I am delighted that Bharti will be leading the effort to deliver the promise of universal broadband connectivity through OneWeb, with the active support and participation of the British Government,” Mittal said.

“OneWeb’s platform will help to reduce the ‘digital divide’ by providing high speed, low latency broadband access to the poor and hard-to-reach rural areas... as one of the largest telecoms operators in India and Africa, I know what a powerful social and economic enabler this can be.”

OneWeb, along with rivals such as Elon Musk’s Starlink, believe that low-earth orbit (LEO) satellites, arranged in “constellations” between about 300 and 1,200 miles up, could bring Earth’s “last billion” internet users online by blanketing even the loneliest mountain with internet signals from space.

On that front Mittal’s interest is obvious: Bharti Airtel, his $40bn flagship company, is India’s second biggest telecommunications firm, holding about a third of its market with 320 million customers. Indeed, its shares increased by 4pc on Friday after the deal was confirmed.

Bharti was already an investor in OneWeb, which collapsed in March after its key backers pulled out. The deal helps save that investment with a major government taking a vested interest in OneWeb’s success.

But Mittal may have deeper motives too. According to Abishur Prakash, head of the Toronto-based Centre for Innovating the Future, the deal is probably driven by three letters: not LEO but Jio, the insurgent low-cost phone telecoms firm that has risen to be India’s biggest mobile operator in only four years.

“[Jio] started off as a very affordable mobile subscription company,” says Prakash, “and now it’s branched off into everything from e-commerce to even thinking about a digital currency. What Jio is doing is forcing all of these other major Indian telecommunications companies to start thinking and acting bigger. OneWeb is one way for Airtel to diversify its holdings.”

Great game for satellites

Mittal’s purse-strings may have been loosened by the news that Facebook had taken a giant $5.7bn stake in Jio’s parent company with plans to integrate the latter’s new online grocery service into the former’s popular WhatsApp.

Satellite internet would also dovetail with Airtel’s substantial footprint in Africa. According to the research firm Omdia, it is the continent’s second biggest mobile operator with more than 100 million subscribers across 14 countries. Africa’s population is predicted to more than double by 2050, yet its infrastructure remains patchy.

These factors help explain why Mittal was willing to invest so substantially in a clearly struggling company, as well as an industry that has failed to escape gravity once before back in the Nineties and still faces serious financial and logistical challenges. Prakash, however, believes there is a bigger contest afoot.

“Just like in the 20th century, when the US and a few other countries dominated information technology through underwater internet cables around the world, the next internet cables are being built in space,” he says.

“The nations that can control the internet and beam it down will have immense geopolitical power... right now everyone is worried about Huawei.”

If the model works, individual LEO corporations might find they can completely bypass existing internet censorship regimes such as China's "great firewall" or Iran's US-built SmartFilter system. That could give the likes of Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos, who are both building their own internet constellations, the power to unilaterally bring populations online.

OneWeb is therefore an important asset in the new “great game” playing out on the edge of Earth’s exosphere between competing navigation, signals and observation networks.

A rival to GPS

The company has also been touted as offering a system that could rival GPS. The UK government hopes to use OneWeb’s low orbit satellites to provide a form of back-up to satellite navigation technology. It will align the UK closely with its South Asian ally after it was booted out of the EU’s Galileo system as a result of Brexit.

In a report last year, the UK’s Foreign Affairs Select Committee called for closer ties with India to head off geopolitical threats. Tom Tugendhat MP, its chairman, said at the time: “We cannot miss the opportunity to partner with India. Trade, security, a shared commitment to the rules-based international system – these are all factors in our growing and evolving partnership.”

China, India’s regional rival, is heavily invested here, through its new Beidou positioning system as well as other private and public internet constellation projects.

Meanwhile, India and China specifically have badly fallen out, with an ongoing border dispute over the Himalayan region of Ladakh that has already killed 23 Indian soldiers. India’s government responded by banning 59 Chinese apps, indicating that it very much sees technology as an arena of global competition.

India’s champions

“India is now championing its technology firms to put India first,” says Prakash. “India does not want to be dependent on SpaceX, or anyone else for that matter, for internet... and so Indian companies may be now thinking in a far more nationalistic way than before in order to build that autonomy and independence.”

OneWeb therefore puts Mittal alongside British officials at the helm of what might just turn out to be a genuine strategic competitor to American, Chinese and European satellite constellations.

That would obviously please Dominic Cummings, intent on securing the UK's technological independence; it would also seem a good fit for Mittal, who has spoken of his hopes for India to benefit from Brexit and floated part of Airtel on the London Stock Exchange.

It is also the sort of international deal that would whet the appetites of Brexiteers, a major international collaboration with an ally far flung from Europe. Unsurprisingly, it has drawn sharp condemnation from some Europhiles who see it as an expensive gambit.

Ruth Kattumuri, co-director of the India observatory and a policy expert at the London School of Economics, says the deal gives the UK an opportunity to partner with India at a time when the nation is growing ever more ambitious in its own high-tech economy.

“India’s space mission is the cheapest in the world,” she says, “and the UK needs to have partnerships for its own space exploration. Over the last ten years the UK has been growing its science and technology projects with India, but this is really going to expand in the future.”

There are still questions over whether OneWeb will succeed. It has already collapsed once, and low-orbit satellite constellations are hugely expensive. Whatever those prospects, the UK is now bound to the ambitions of one of India’s technology superpowers.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance