10 accidental inventions that made billions

Serendipitous innovations that will amaze you

Tutatamafilm/Shutterstock

Believe it or not, some of the most lucrative products of all time were discovered by mistake.

From Nutella to Teflon, we reveal the stories behind 10 accidental inventions that made billions and changed the world.

All dollar amounts in US dollars.

Corn flakes

SEGNER & CONDIT, publisher, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Today's breakfast staple was invented by chance one afternoon in 1894. Michigan sanitarium director Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (pictured) and his brother Will Keith Kellogg were attempting to make granola when they absent-mindedly left the wheat to dry out.

They pressed the stale grains anyway and produced the first ever batch of crispy cereal flakes.

Corn flakes

Kellogg Company, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

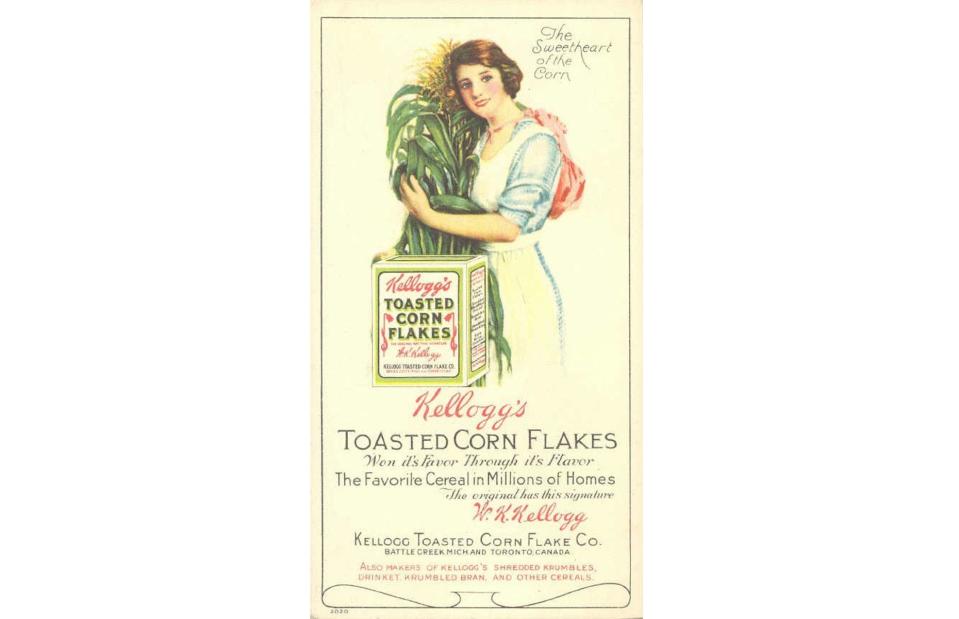

A religious family, the Kelloggs were convinced a grain-based vegetarian diet would suppress carnal passions and "unhealthy" urges. Having obtained a patent, Will Keith Kellogg decided to mass-market the creation in 1906.

He swapped corn for wheat and added malt sugar to make the flakes more palatable, causing him to fall out with his anti-sugar brother in the process.

Corn flakes

Kellogg Company, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Marketed as a healthy breakfast cereal, corn flakes were a big hit with the American public from the get-go.

By 1910, Will Keith Kellogg's Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, the precursor to The Kellogg Company, was turning over $1 million a year, and corn flakes have gone on to net the firm billions of dollars over the years.

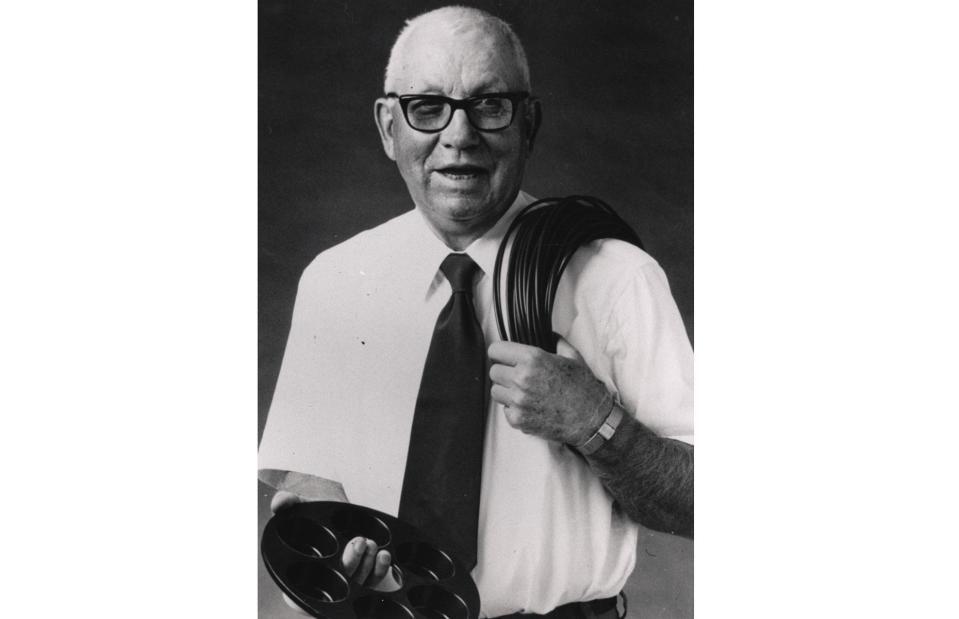

Super Glue

Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty

In 1942, Eastman Kodak scientist Harry Coover Jr. (pictured) was looking for a suitable material to create clear plastic gunsights for the war effort, and stumbled across cyanoacrylate.

Frustrating Coover no end, the substance was ridiculously sticky, bonding to almost anything. Needless to say, it was rejected as unsuitable for the project.

Super Glue

Courtesy Science/Amazon

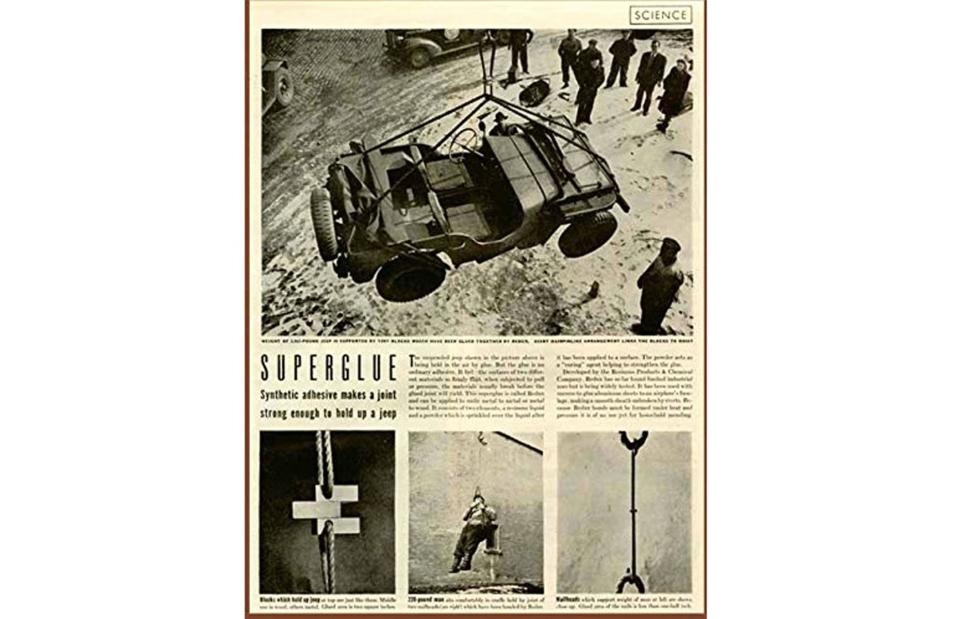

Several years later, Coover was working with his Eastman Kodak colleague Fred Joyner on heat-resistant jet plane canopies.

Joyner discovered Coover's work on cyanoacrylate and the pair re-tested its properties, finally waking up to the substance's incredible commercial potential as an ultra-strong, fast-acting adhesive.

Super Glue

TY Lim/Shutterstock

The adhesive was launched in 1958 as the rather prosaic Eastman #910, and gained its Super Glue moniker in the 1970s, along with bona fide household name status.

Tubes of the stuff flew off the shelves. By the late 1980s, sales of ultra-strong instant glues had hit $100 million a year.

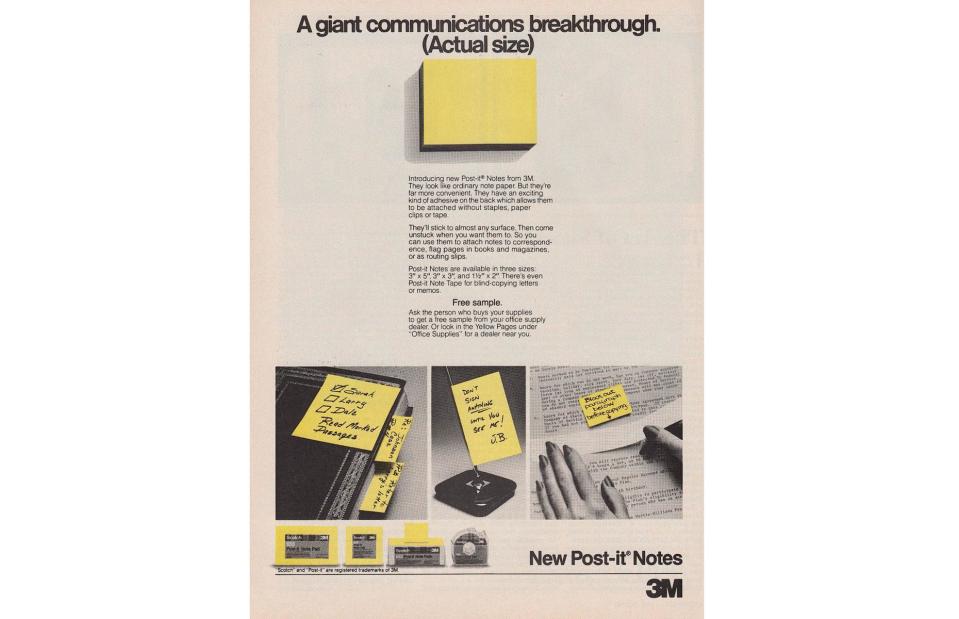

Post-it notes

Courtesy 3M

Unlike Harry Coover Jr., in 1968, scientist Dr Spencer Silver was looking to develop an ultra-strong adhesive for 3M (formerly the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company).

But the chemistry ace ended up inventing a low-tack, reusable, pressure-sensitive glue instead. Silver struggled to promote the adhesive and find a suitable application until 1974, when his 3M colleague Art Fry suggested it could be used to create stickable, reusable bookmarks.

Post-it notes

Courtesy 3M

The bookmarks' yellow hue came about as the team working on the project could only get hold of yellow scrap paper, and decided to stick with the colour.

The product was launched by 3M in 1977 as the Press 'n Peel bookmark but, following lacklustre sales, 3M opted to re-market it as a stickable, reusable note.

Post-it notes

Lesterman/Shutterstock

Relaunched as Post-its in 1979, the tacky notes were an overnight success in the US. Post-its debuted in Canada and Europe in 1981 and have since conquered the world.

Every year, 3M, which holds the trademark for the name and distinctive yellow colour, sells 50 billion of the things.

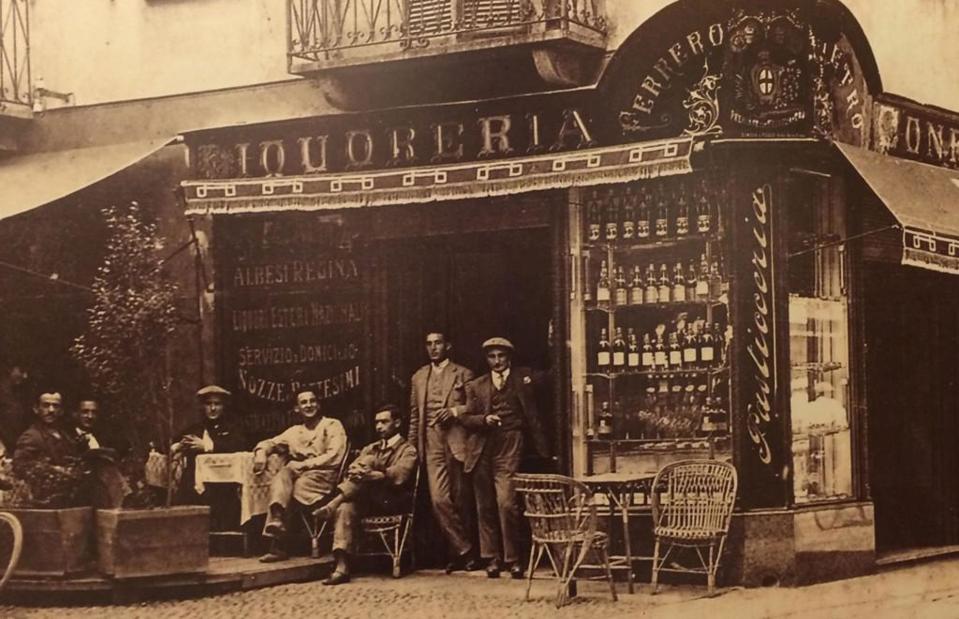

Nutella

Courtesy nutella.com

Back in 1946, Pietro Ferrero, a pastry chef from Alba in Piedmont, Italy wanted to create an affordable chocolate confection. The only catch? Cocoa beans were astronomically expensive and in seriously short supply in post-war Italy.

To get around this, Ferrero bulked out the sweet treat with hazelnuts, which were cheap and plentiful.

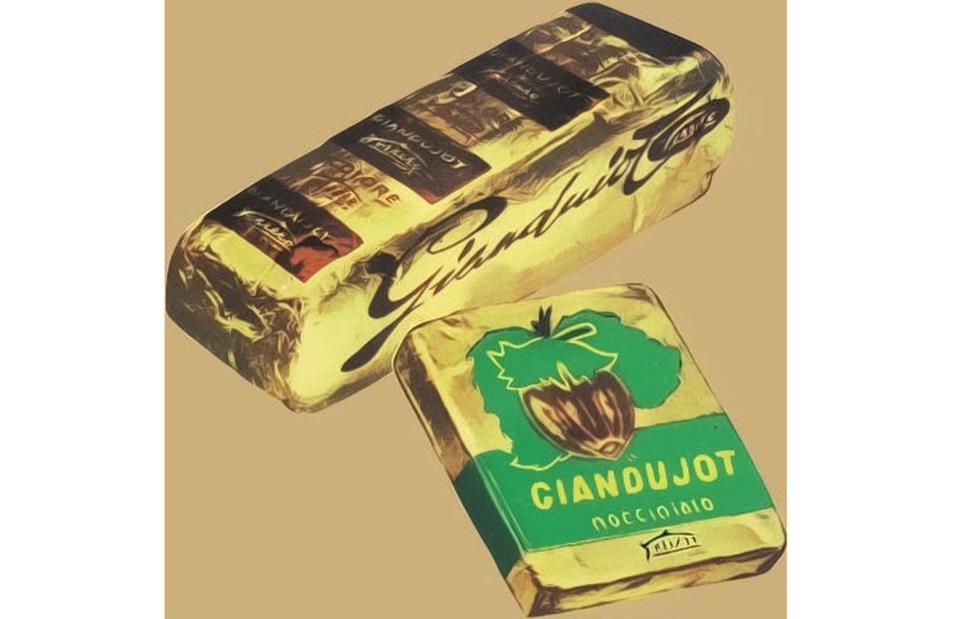

Nutella

Courtesy nutella.com

That same year, Pietro Ferrero launched Giandujot, a hard hazelnut and chocolate confection that had to be cut with a knife. The budget-friendly confection sold well but it wasn't until the scorching hot summer of 1949 that things really began to take off for the Ferrero family business.

On one particularly sizzling afternoon, a batch of Giandujot completely melted, making it creamier and more delicious.

Nutella

Tutatamafilm/Shutterstock

Pietro's son Michele Ferrero added vegetable oil and bottled the concoction, calling the spread Supercrema. In 1964, he tweaked the formula, renamed it Nutella, and marketed the product throughout Europe.

Sales exploded and Nutella became a global phenomenon, making billions for the Ferreros. These days, a jar of the sweet spread is sold every 2.5 seconds.

Botox

Courtesy Carruthers & Humphrey

Botulinum toxin, or Botox as it's commonly known, was first used to treat eye muscle disorders in 1977. Vancouver-based eye specialist Dr Jean Carruthers (pictured) started treating her patients with the toxin during the mid-1980s and began to notice a very curious side-effect.

When injected in the forehead and eye area, the toxin smoothed fine lines and evened-out deeper wrinkles.

Botox

Courtesy Carruthers & Humphrey

In 1987, a patient who had been successfully treated for eye muscle spasms became upset when she was told she no longer required Botox injections, having become accustomed to a wrinkle-free visage.

Dr Jean Carruthers told her dermatologist husband, Dr Alastair Carruthers (pictured), about the patient's reaction, and they realised they'd discovered a near-miraculous anti-ageing treatment.

Botox

Lidarina/Shutterstock

Receptionist Cathy Swann volunteered to be a guinea pig and was delighted with the results. The Carruthers published a scientific paper in 1991 that won over colleagues concerned about the toxin's safety, and Botox was eventually granted FDA approval for cosmetic use in 2002.

Since then, millions of people worldwide have been treated, and the Botox industry is forecast to be worth a staggering $13.5 billion (£10.6m) by 2035.

Slinky

Courtesy James Industries

In 1943, Philadelphia shipyard naval engineer Richard James was working on a tension spring system that could stabilise objects on ships during stormy weather.

One day, he clumsily dropped a spring and watched in amazement as it manoeuvred across a desk, some books, and onto the floor.

Slinky

Retro AdArchives / Alamy Stock Photo

Certain the contraption would make a fun children's toy, James spent a year perfecting it, settling on a design made from 98 coils of high-grade steel.

James' wife Betty came up with the Slinky name and a classic toy was born. The couple then borrowed $500 and had 400 units produced.

Slinky

Roger McLassus, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Persuading retailers to stock the plain-looking plaything was a challenge, but the couple was finally given a chance to promote Slinky in 1945 at Philadelphia's Gimbals department store.

All 400 units sold within 90 minutes, and the couple never looked back. To date, more than 350 million Slinkys have been sold worldwide.

Scotchgard

US Department of Commerce, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Another accidental discovery by a 3M scientist, Scotchgard stain and water repellent was invented by mistake by chemist Patsy Sherman in 1952 at the company lab in Minnesota.

Sherman was attempting to develop a type of fluorochemical rubber that wouldn't deteriorate if exposed to jet fuel.

Scotchgard

Courtesy 3M

During one of her experiments, the chemist split some of the liquid rubber on an assistant's tennis shoe. Try as they might, nobody in the lab could remove the spillage as it seemed to repel anything it came into contact with.

This led Sherman to believe the liquid could make an effective stain and water repellent.

Scotchgard

Courtesy 3M

Along with her colleague Samuel Smith, Sherman refined the repellent, which 3M launched as Scotchgard in 1956.

The product sold like hot cakes and still does, though the formula was changed in 2000 following concerns over the toxicity of its main ingredient, perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS).

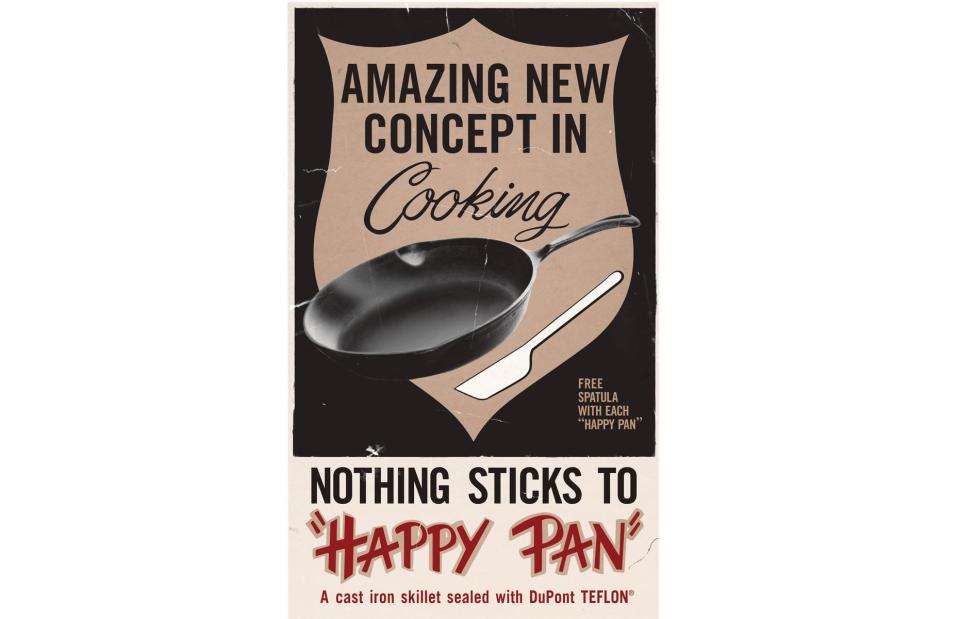

Teflon

Courtesy Hagley Museum and Library

In 1938, Roy J. Plunkett, a chemist at DuPont in New Jersey was attempting to create a new refrigerant using tetrafluoroethylene gas (TFE) when he noticed something odd.

After chlorinating the gas in a cylinder with dry ice, Plunkett opened the valve to release the gas. Nothing came out, but the cylinder's weight remained the same.

Teflon

Courtesy Hagley Museum and Library

Seriously puzzled, Plunkett cut open the cylinder and discovered a remarkably slippery white powder. The gas had solidified into a polymer called polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which had amazing anti-friction, heat-resistant, and anti-corrosive properties.

DuPont patented the polymer in 1941 and trademarked the name Teflon in 1945.

Teflon

trozzolo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By 1948, DuPont was producing 900 tonnes of the wonder polymer annually. A significant money-spinner for the chemicals giant over the years, versatile Teflon has since been used in everything from non-stick cookware and nail polish to windscreen wipers and wiring for computers.

Splenda

Oxfordian Kissuth, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

In 1975, Shashikant Phadnis, a young Indian graduate student at Queen Elizabeth College (now part of King's College London), was researching compounds that could be used as insecticides.

Phadnis and his tutor, Leslie Hough, were particularly interested in a compound they synthesised by adding toxic sulfuryl chloride to sugar.

Splenda

Iryna Imago/Shutterstock

Hough asked Phadnis to "test" the chemical, but the student misheard the instruction and thought his tutor requested that he taste it instead. Phadnis duly obliged, disregarding the potential dangers, and found the compound to be extremely sweet and safe for human consumption.

The student reported his findings to Hough, who realised the compound had strong potential as a sugar substitute.

Splenda

michael going / Alamy Stock Photo

Hough and Phadnis teamed up with British sugar firm Tate & Lyle to develop the compound, which they named sucralose.

The substance was marketed as Splenda following FDA approval in 1998. By 2006, it had become the number one artificial sweetener in the US with a 62% market share and annual sales of $212 million (£167m).

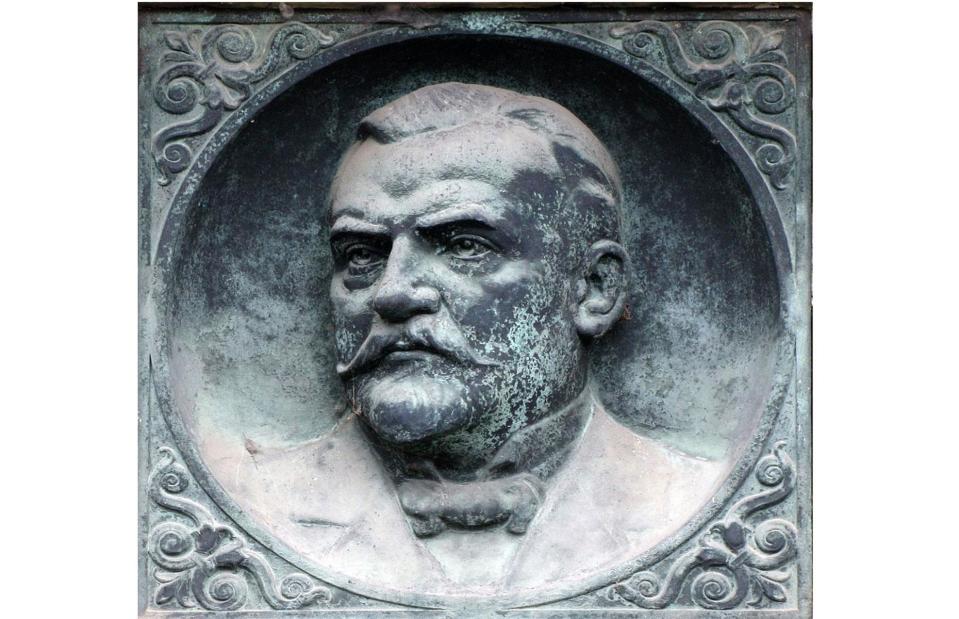

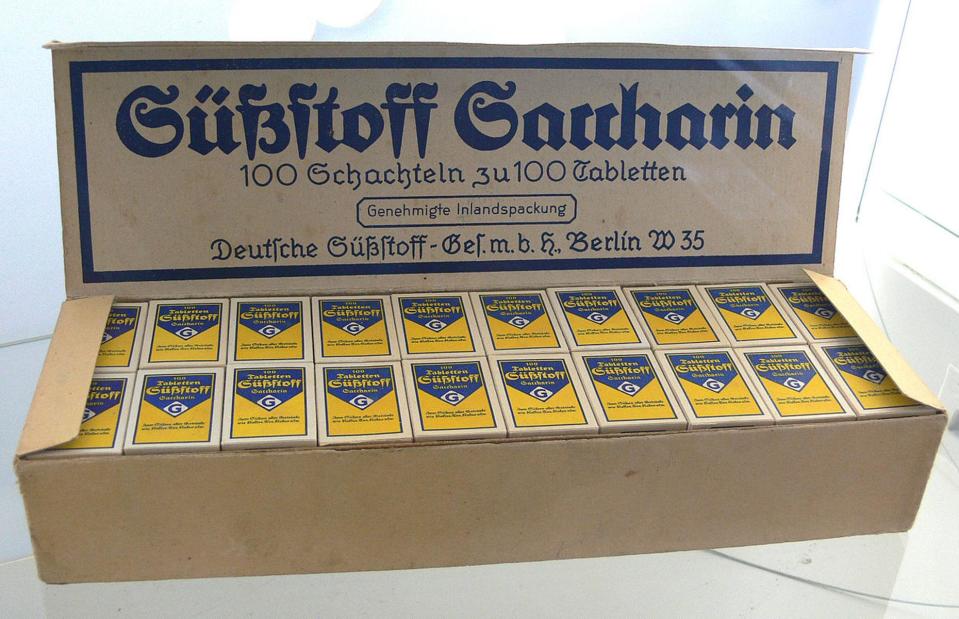

Saccharin

Klewic, CC BY 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Almost a century before Phadnis made his accidental find, chemist Constantin Fahlberg discovered the sweetener saccharin purely by chance.

In 1879, Fahlerg was experimenting with different coal tar derivatives at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Not one for OTT hygiene, the sloppy scientist forgot to wash his hands one evening after a long day in the lab.

Saccharin

Photo: User:FA2010, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At home later that evening he ate a slice of bread and noted it tasted very sweet. Fahlberg put two and two together and worked out that the sugary taste had come from the compound benzoic sulfimide he'd been working on.

The chemist published his findings and obtained a patent for the discovery, which he named saccharin.

Saccharin

Elbud/Shutterstock

Fahlberg began production of the new sugar substitute in Germany in 1886 and made a fortune from it, becoming a very rich man in his time. The zero-calorie saccharin eventually achieved global popularity in the 1960s and 1970s, when it became the go-to sweetener for dieters worldwide.

Now discover 15 genius inventions that were ridiculed but are now everyday products

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance