Big tech has distracted world from existential risk of AI, says top scientist

Big tech has succeeded in distracting the world from the existential risk to humanity that artificial intelligence still poses, a leading scientist and AI campaigner has warned.

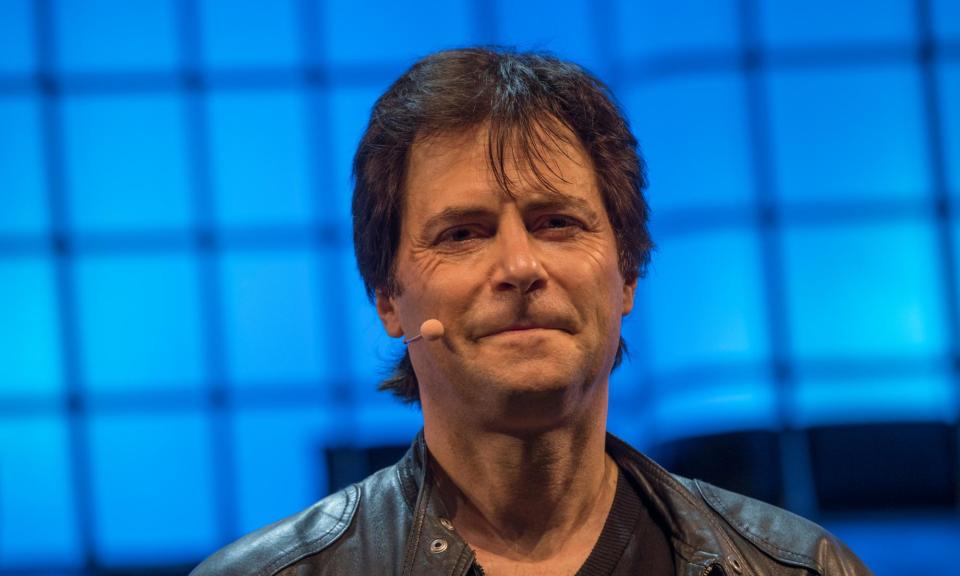

Speaking with the Guardian at the AI Summit in Seoul, South Korea, Max Tegmark said the shift in focus from the extinction of life to a broader conception of safety of artificial intelligence risked an unacceptable delay in imposing strict regulation on the creators of the most powerful programs.

“In 1942, Enrico Fermi built the first ever reactor with a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction under a Chicago football field,” Tegmark, who trained as a physicist, said. “When the top physicists at the time found out about that, they really freaked out, because they realised that the single biggest hurdle remaining to building a nuclear bomb had just been overcome. They realised that it was just a few years away – and in fact, it was three years, with the Trinity test in 1945.

“AI models that can pass the Turing test [where someone cannot tell in conversation that they are not speaking to another human] are the same warning for the kind of AI that you can lose control over. That’s why you get people like Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio – and even a lot of tech CEOs, at least in private – freaking out now.”

Tegmark’s non-profit Future of Life Institute led the call last year for a six-month “pause” in advanced AI research on the back of those fears. The launch of OpenAI’s GPT-4 model in March that year was the canary in the coalmine, he said, and proved that the risk was unacceptably close.

Despite thousands of signatures, from experts including Hinton and Bengio, two of the three “godfathers” of AI who pioneered the approach to machine learning that underpins the field today, no pause was agreed.

Instead, the AI summits, of which Seoul is the second following Bletchley Park in the UK last November, have led the fledgling field of AI regulation. “We wanted that letter to legitimise the conversation, and are quite delighted with how that worked out. Once people saw that people like Bengio are worried, they thought, ‘It’s OK for me to worry about it.’ Even the guy in my gas station said to me, after that, that he’s worried about AI replacing us.

“But now, we need to move from just talking the talk to walking the walk.”

Since the initial announcement of what became the Bletchley Park summit, however, the focus of international AI regulation has shifted away from existential risk.

In Seoul, only one of the three “high-level” groups addressed safety directly, and it looked at the “full spectrum” of risks, “from privacy breaches to job market disruptions and potential catastrophic outcomes”. Tegmark argues that the playing-down of the most severe risks is not healthy – and is not accidental.

“That’s exactly what I predicted would happen from industry lobbying,” he said. “In 1955, the first journal articles came out saying smoking causes lung cancer, and you’d think that pretty quickly there would be some regulation. But no, it took until 1980, because there was this huge push to by industry to distract. I feel that’s what’s happening now.

“Of course AI causes current harms as well: there’s bias, it harms marginalised groups … But like [the UK science and technology secretary] Michelle Donelan herself said, it’s not like we can’t deal with both. It’s a bit like saying, ‘Let’s not pay any attention to climate change because there’s going to be a hurricane this year, so we should just focus on the hurricane.’”

Tegmark’s critics have made the same argument of his own claims: that the industry wants everyone to speak about hypothetical risks in the future to distract from concrete harms in the present, an accusation that he dismisses. “Even if you think about it on its own merits, it’s pretty galaxy-brained: it would be quite 4D chess for someone like [OpenAI boss] Sam Altman, in order to avoid regulation, to tell everybody that it could be lights out for everyone and then try to persuade people like us to sound the alarm.”

Instead, he argues, the muted support from some tech leaders is because “I think they all feel that they’re stuck in an impossible situation where, even if they want to stop, they can’t. If a CEO of a tobacco company wakes up one morning and feels what they’re doing is not right, what’s going to happen? They’re going to replace the CEO. So the only way you can get safety first is if the government puts in place safety standards for everybody.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance