The British Museum’s Burma to Myanmar explores a country famous for its isolation

The British Museum’s new Burma to Myanmar show is the first major exhibition in the UK to explore the history of a country famous for its isolation.

The guiding thread behind the exhibition is Myanmar’s diversity and complexity. It whisks us from its deep history right up to its contemporary troubles, with stops along the way to explore the period of British colonial rule.

It makes for a slightly bewildering journey, but there are a few points that stand out.

The British influence – both on Myanmar’s history and its contemporary position – is clear. Burma, the name given to Myanmar by the British, reflects the country’s dominant ethnic group, the Bamar (the military junta renamed the country in 1989).

There were misunderstandings in relations between the kings of Britain and Burma from the very beginning. One of the first pieces in the exhibition is a gold and ruby-studded letter sent by King Alaungpaya to George II in 1756. Thinking it was a gift, rather than a letter, George II did not reply, causing great offence to his regal counterpart.

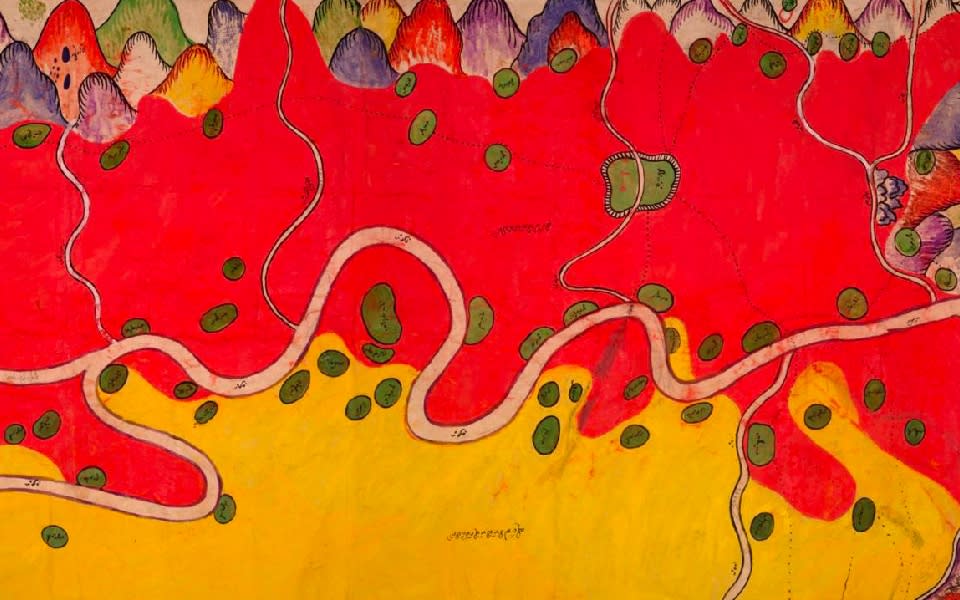

The exhibition continues with a whistle stop tour of Myanmar’s different regions and ethnic groups, taking in the influences of its neighbours and the dominant influence of Buddhism.

One poster advertising sunlight soap is adorned by General Mahabandula, leader of the Burmese army in the First Anglo-Burmese War, an intriguing mix of Burmese patriotism and western consumerism.

Since independence, Myanmar has had a chequered history. The exhibition touches on these issues but could have done more to explore them. A single photograph relates the plight of the Rohingya, who are facing genocide.

In short, covering so much in such a short space of time makes it difficult for the curators to really explain why Burma has become Myanmar – and what the consequences are.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance