Car-nage: 1963 Safari Rally lives on as the most brutal running of the world's toughest rally

What does it take to win the notorious Safari Rally in East Africa, the world’s toughest such event? “You need patience, you need to be rational and you need to be quick,” says Fred Gallagher. He should know. This 68-year-old rally co-driver and organiser has plied his trade alongside the crème of the sport in the World Rally Championship.

Co-driving with “Flying Finn” Juha Kankkunen, Gallagher won his first Safari in 1985, twice more with Swede Björn Waldegård and he’s been on the podium many other times.

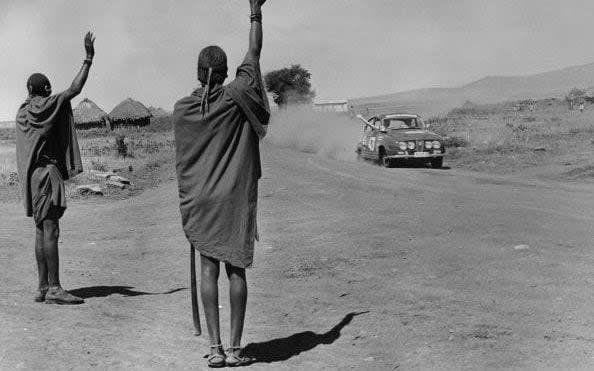

Traditionally held in spring, during the wet season, the event was inaugurated in 1953 as the East African Coronation Safari. Running through Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika, the Safari is quite simply the toughest test of crew and machine in the calendar. Apart from the mud, the floods, the lions and rhinos, the partisan crowds and unremitting dust, plus the ghastly bottomless pits of gunge to negotiate, it was so bloomin’ long.

“It was relentless,” says Gallagher, who is now rally director of Rally The Globe. “When I competed from the mid-80s to the mid-90s, [something like the UK-based] RAC Rally could have up to 50 special stages of between five and 40km long where you had to go quick, but between them you had time to see your service crew and grab something to eat.

“But the first year I did a Safari it was 5,500km, pace-noted all the way and basically going as quick as you could while trying to keep your car together.

“It was divided into three legs, so there were two halts, but how much rest you got depended on how well you were going. I remember turning up in the morning to restart a leg and we'd had eight hours of sleep, but when I got to the parc ferme there were maybe 10 cars in there and other cars were coming in; and 10 minutes later they were on their way again..."

“It always rains…”

Rauno Aaltonen, one of the original “Flying Finn” rally drivers, did his first Safari in 1962 driving a Mercedes-Benz 220SE, though he and co-driver Peter Goode were forced to retire near Mombasa. He liked the event and reckons that was down to the self-reliance it required of the crew, which suited his Finnish upbringing.

“The rally was always at Easter,” he says, “which varies according the position of the moon, but the weather in Africa remains fixed; it always rains. But I loved it; the jungle, the river crossings, getting stuck in the mud... there were no stages, it was a road race, 5,000km long.”

In later years, Aaltonen would always carry lengths of steel cable with winches and ground anchors to haul the car out of trouble. “You have to find ways of getting round,” he says describing stages around Lake Victoria and Mount Kenya, which were nothing less than an all-out drive through the rainforest.

And that mud; a treacherous black clay, which clung to the cars and crews. “It’s called black cotton, or vertisol,” says John Davenport, former Austin Rover rally chief and author of a definitive history of the Safari.

“You hear all the stories about the Safari, but it doesn’t really sink in until you actually go. My first Safari was in 1969, we were in the recce [reconnaissance] car, which we parked at the side of the road. It was in gear with the handbrake on, but we quickly realised it hadn’t stopped moving; it was sliding on that horrible mud, down the crown of the road and into the ditch.”

Davenport says the mud was so tenacious that it would pack the wheel arches of a car “until the wheels just wouldn’t go round.

“Go absolutely flat out and you’d get into trouble. And if you got into trouble, you’d have to be resourceful to get out of it,” he says, citing Joginder Singh, three times Safari winner, who was a trained mechanic, which stood him in good stead. “If the car went wrong, he’d just climb out and mend it.”

Aardvarks and Aaltonen

Aaltonen came across black cotton in 1963 which is where our story begins on the 11th running of the event, now called the East African Safari rally.

“Two things to watch out for on the Safari and they both have two As,” jokes Davenport. “Aardvarks and Aaltonen.”

Aaltonen had a contract with the British Motor Company (BMC) whose motorsport department was run by the legendary Stuart Turner. "I persuaded Stuart to enter the Safari," he says."They didn't really have a suitable car, though they'd just launched the MG 1100 [ADO16] so that's what we got. But it had 12-inch wheels, a wide track, with hydrolastic suspension and a transverse engine."

Small wheels weren't great in mud, the hydrolastic suspension tended to pitch under braking and squat under hard acceleration, the wide track restricted ground clearance and "the transverse engine restricted the length of the suspension arms so it was difficult to raise the ride height and keep the steering geometry and you needed longer dampers which we didn't have," Aaltonen pithily observes.

On the start for this 5,131km rally were 84 cars including eight factory teams. Mike Tippett, amateur Peugeot historian who scoured local sources for a history of Peugeot on the event, says there were 18 Fords, 11 Peugeot 404s and four 403s, nine Fiats, seven VWs, seven Morrises, five Saabs and, for the first time, four Nissans, with the same number of Mercedes-Benz and Rovers.

Cars and drivers tend not to win the Safari just once. A VW Beetle won the inaugural 1953 event, going on to win the event four times. A Mercedes-Benz “Pontoon” 219 won twice in a row, Peugeot’s 404 won four times and in more recent years Toyota’s Celica and Mitsubishi’s Lancer have swept the board for years at a stretch.

As for the drivers: Shekhar Mehta and Carlo Tundo have won it five times each; Waldegård, Colin McRae, Joginder Singh and Baldev Chager have won three times each, while many have won it twice.

Peugeot 404: “None of that chintzy pressed-steel garbage”

Back in 1963, the Peugeot 404, which finished in fourth place in 1961 and second in 1962, was beginning to look, according to many, like a shoo-in for its first win.

Launched in 1960, the 404 was styled by Peugeot's long-term collaborator, Pininfarina. "A very good, straightforward, new 1.6-litre car from France," said The Motor magazine test in 1961. Priced at £1,300 in the UK, the 404 was far from quick, with a 0-50mph time of 14.5sec and a top speed of just 85mph, but it was tough and reliable.

"Cars need to be strong, but lightness is often overlooked," says Gallagher about Safari suitability. "We won in a Toyota Celica twin-cam turbo, which was rear-wheel drive at a time of the 4x4 era. It was simple, it was light and it went through mud just as well as the 4x4 cars."

At 1,041kg the 404 was hardly a featherweight, but as Tippett observes: "It was simple and well designed for rough conditions, with a massive torque tube, enormous suspension travel, comfort (important for crews in endurance events) and it was also strong and robust mechanically, for example, the front suspension arms were in solid steel; none of that chintzy pressed-steel garbage..."

At the wheel was Polish-born, naturalised Kenyan, Zbigniew 'Nick' Nowicki and co-driver Paddy Cliff, both aiming at ending years of Mercedes-Benz, VW and Ford domination.

"He was a farmer I think," recalls Aaltonen. "Tough and resourceful and well used to driving in deep mud; mind you everyone in Kenya and Tanzania was good at driving in mud, even the women, in fact cars were mostly what they talked about."

"He was not miniature in any respect," says Davenport, "but utterly relaxed. You couldn't imagine him getting excited about anything at all, even an elephant in the road."

"A nice chap, Polish and a bit fat," says Gunnar Palm, a contracted Saab co driver. "And Peugeot was well organised, with good cars."

Saab 96: "A write-off, even the dashboard fell out"

Erik Carlsson and Palm, though, were equal favourites; in January they'd won the Monte Carlo Rally and were clearly at the top of their game, bringing European speed and flair in their advanced Saab 96. In the 1962 Safari, Carlsson and his then co-driver, Karl Erik Svensson, had come sixth, and his wife, Pat Moss-Carlsson, a phenomenally talented rally driver and Stirling Moss's sister, with Anne Wisdom-Riley as co driver, had come third behind the Nowicki/Cliff 404.

And what of the Saab 96? "An improved Swedish small car, which combines charm with very notable performance," concluded The Motor's testers. At £885 2s and 6d, this 800kg, 72mph, two-door saloon built by Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget, was just the thing for rough roads, so could the dream team make it to the chequered flag? Palm takes up the story…

"It took forever to get from Europe to Embakasi airport in Nairobi with four different stopovers on the way from Stockholm," he recalls, "and when I got there, well there was the heat of course and in Sweden a black man was a rare sight back then."

They were taken by the Safari rally organisers to stay at one of the best hotels in the city, The Norfolk. "We felt like kings," says Palm, "but we didn't stay there long because we had to do the recce."

Picking up a Saab 96 from the local dealer they proceeded to drive the southern rally loop to Dar es Salaam and then the northern loop.

"It took about a week to do the rally distance at sensible speeds," says Palm, "but when we got back the car was pretty much a total write-off, even the dashboard fell out. The cars had to be original and it was a real test of the best cars for these sorts of roads; a real adventure."

In those days no one thought a non-Africa local could ever win the Safari and it took Palm and Hannu Mikkola in a Ford Escort RS1600 to finally crack that hex with a win in 1972.

"Local knowledge was huge," says Tippett, "with the international superstars struggling due to their unfamiliarity with the terrain and perhaps also because of the difficult conditions."

"The thing was to drive the rally so carefully," says Palm. "You couldn't go as fast as we did and it took us a long time to work out that only if the car fell apart as you crossed the finish line, you'd done it right. Local knowledge was of such vital importance. They all spoke Swahili and they knew all sorts of tricks and things to avoid. It wasn't always fair; it was seen as a battle between the locals and invaders, us."

John Davenport illustrates the point telling a story about Bert Shankland, a Scottish-born, Tanzanian resident and Peugeot dealership workshop manager, who won the Safari in a Peugeot 404 in 1966 and 1967. "He was driving down a dead straight track near the town of Mackinnon Road, but he was weaving from side to side. When I asked Chris Rothwell, his co-driver, why he was doing that he said he was splashing through the puddles to wash the mud out of the wheel arches..."

"I hope it's going to be wet"

Carlsson was very much the star in Nairobi and his interview with the Kenyan Daily Nation before the off proved prophetic.

"I hope it’s going to be wet," he said, "as I'm in a small car and wet conditions favour these as opposed to the larger models."

It tipped down...

Publicity gimmicks abounded at the Nairobi start on April 11. Carlsson and Palm had to race Kenyan Olympic sprinter Seraphino Antao over the first 100 yards of the rally and despite wearing a suit and ordinary shoes, Antao thrashed them, but that was the last time Carlsson was bettered in the first part of the rally. Rivals crashed and rolled over in the terrible conditions and at quarter rally distance in Kampala, the Saab crew were in a comfortable lead.

Getting back to Nairobi was a mudbath, though, and they were lucky to get through at all, let alone with their lead intact.

At the half way point at Nairobi only 43 competitors remained, with local driver Beau Younghusband in a Ford Cortina in second place behind Carlsson and Palm. As Tippett reported: "At Nairobi, all the remaining competitors were compelled to have a 12-hour rest as it was predicted that the second half would prove to be the most difficult."

In their 404, Nowicki and Cliff were playing a waiting game.

"We were leading at the halfway point," says Palm, "before we started on the South Loop towards Mbulu in Tanzania."

This would have been about ¾ distance and Carlsson was going well.

"There are no myrslok in the whole of Africa"

"It was the middle of the night and Erik wasn't driving really fast," says Palm. "We were on a dirt road between high grass and this big thing just ran out and we hit it, hard. We felt it right under the floor pan."

Carlsson and Palm got out but couldn't see anything amiss so continued. It soon became clear, however, that the car was badly damaged, with the anti-roll bar smashing its way to freedom and taking other suspension parts with it, jamming the steering. They stopped and worked on the car, even replacing a wishbone. Their mechanic was at Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania. He'd even dismantled his car to cannibalise the bits he'd need to keep Carlsson and Palm in contention, but before they could get to him the battered Saab collapsed – Carlsson never did win a Safari.

"It was an aardvark, of course," says Palm, "but the Swedish papers reported next morning that we'd hit an anteater or myrslok. But there are no myrslok in the whole of Africa, so everyone said ‘They are bloody lying’! It became quite legendary in Sweden; there's a generation of people who know that myrslok means you aren't telling the truth."

Further back, in their 404, the ever-cool Nowicki and Cliff moved up a place and then another when Younghusband's Cortina holed its sump. The mud was incredible, and sportingly Nowicki and Cliff stopped to help rally leader and fellow Kenyans Peter Hughes and William Young pull their Ford Anglia out of a lake of ooze. Rauno Aaltonen had been running strongly, too, but the wheel arches of their MG filled with black cotton which brought them and all the other MGs to a halt.

"The Unsinkables" legend is born

Steady at the helm, Nowicki and Cliff stayed in the lead until the chequered flag. The mud and conditions put paid to most of the other competitors, broken down, crashed or out of time. Just seven finishers made it to Nairobi on April 15; eight per cent of the starters.

They became known as "The Unsinkables"; Hughes and Young in the Anglia came second, with Cardwell and Lead third in a Mercedes 220, followed by the great Joginder Singh and his brother Jaswant in a Fiat 2300, Lionnet and Philip in another 404, Bathurst and Jaffray in a Peugeot 403 and, almost incredibly, Brits Bill Bengry and Gordon Goby in a Rover P5 – who knew that car was so tough?

"What a Rally!" exclaimed Motor Sport magazine in May 1963. "And what a tough, useful car, the conscientiously-built Peugeot has once again proved itself."

"Sensationally destructive," is how the scribes at Motor Sport went on to describe the '63 Safari and its world-record attrition rate. Except that five years later in 1968 the rains struck again.

Paired with Swedish driver Bengt Söderström in a twin-cam Lotus Cortina, Gunnar Palm retired after being stuck in a mud pit for eight hours not far south of Nairobi.

"When it rains on the slopes of Kilimanjaro, you'd better stay at home," says Palm. "We knew it would be murder going through there but it turned out to be hell. In the end we sort-of gave up.

"And after the win in 1972, I hang [up] my hat, because that was really enough. Any rally driver of calibre will have tried the Safari; it's no shame not to have won it, but there's one big painting in my study at home, which is of the Safari in 1972. It's my only picture on the wall and it's a nice thing to see every morning."

So it was another and different set of magnificent-seven finishers in 1968, another lot of “Unsinkables”, who forded, smashed and dragged their cars all the way to the finishing ramp…

Well, all except for one crew and one car. Against all the odds, Nick Nowicki and Paddy Cliff won again in a Peugeot 404. Incredible.

Many thanks to all who generously helped with this article including Rauno Aaltonen, Gunnar Palm, John Davenport, Fred Gallagher and Mike Tippett.

John Davenport is author of Safari Rally: 50 Years of the Toughest Rally in the World.

Fred Gallagher is rally director of historic rally organiser Rally The Globe - rallytheglobe.com

For tips and advice, visit our Advice section, or sign up to our newsletter here

To talk all things motoring with the Telegraph Cars team join the Telegraph Motoring Club Facebook group here

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance