Why Nigel Farage is targeting the Bank of England to raise billions

Nigel Farage has proposed a £40bn raid on banks to plug holes in the Government’s finances.

The leader of the Reform UK party wants to cease interest payments to commercial banks on the reserves they hold at the Bank of England.

His policy, which partly echoes the workings of the European Central Bank, promises to save the Treasury billions each year at a critical moment for the indebted nation.

It also comes at a critical time politically: with an election just weeks away, both Labour and the Tories are keen to convince voters they are the safest pair of hands to look after the economy.

But whoever walks into Number 10 Downing Street come July 5 will find themselves severely constrained by an unusual force: the Bank of England.

Jeremy Hunt had to send more than £44bn to the central bank last year.

That is bigger than the entire budgets for some government departments. Defence is getting just under £33bn for 2024 to 2025, for instance.

Hunt – or Rachel Reeves, should Labour win – can expect to sign another cheque to the Bank for £34.5bn this financial year.

It will go, with £20bn or so flowing from Whitehall to Threadneedle Street every year for the foreseeable future.

The reason? The Bank of England’s crisis-era money-printing spree and the somewhat unusual way it was set up.

Threadneedle Street created hundreds of billions of pounds to buy bonds during the financial crisis and the pandemic, staving off a financial crunch and pushing down borrowing costs in the wider economy.

Buying bonds creates financial risk. Successive chancellors offered the Bank of England an indemnity against any losses. They did so because the idea of losing money seemed a far off threat.

This bond buying spree – known as the quantitative easing (QE) – made the Bank a profit when interest rates were low, which was passed to the Treasury.

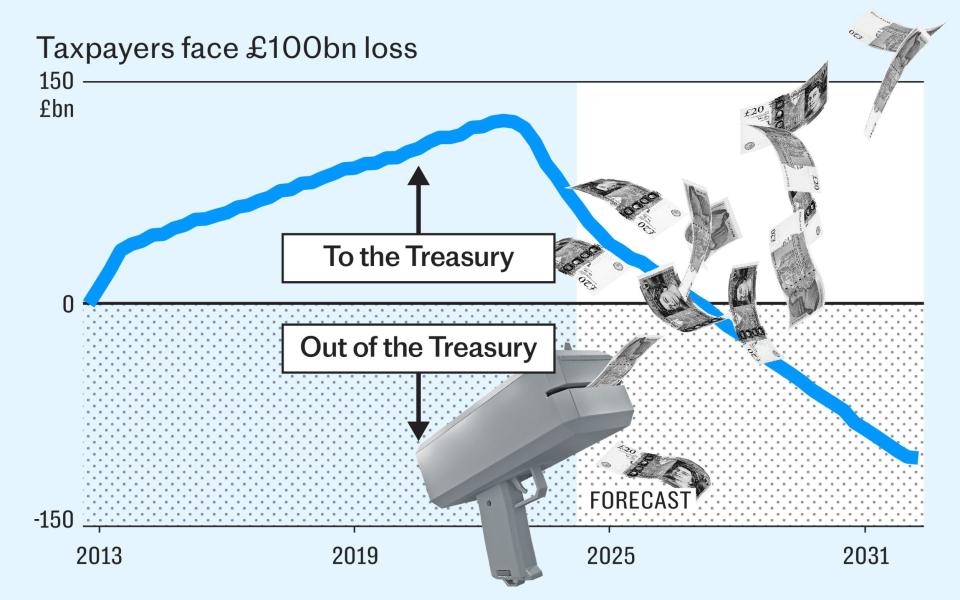

Up until 2022, the Treasury had made £124bn from the arrangement.

Now borrowing costs are high, the Asset Purchase Facility (APF), as the Bank calls the setup, is losing money hand over fist. And it is taxpayers who are on the hook to make up the losses.

The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that quantitative tightening (QT) – the process by which the Bank slims down its bond holdings – will cost taxpayers more than £106bn by 2032.

The bill is so large it has effectively made the Bank of England a critical player in the Government’s fiscal policy – the matter of taxation, spending and borrowing.

“The Bank’s asset sales are constraining the Government’s spending, with its current fiscal rules,” says Rob Wood at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

Public finances are already tight. The Government only meets its target to have debt falling as a share of GDP in five years’ time by a margin of less than £9bn.

With little headroom, key government policies are approved or delayed because of the finest financial margins in the forecasts.

Even worse, the cost of QT to the Treasury is highly unpredictable.

In July of last year, the OBR predicted a net loss from the scheme of £63bn. By November, that projected black hole had doubled to £126bn. Then by March of this year it had dropped back a little to £106bn.

The total cost depends both on policies set by Bank of England officials and on interest rates, which appear to be staying higher for longer.

It is up to the Bank of England to decide the timing of QT and interest rates – its operational independence is considered sacrosanct.

But the fiscal straitjacket this arrangement is placing on the Government has led to outcry in some quarters.

“Nobody challenges the independence of the Bank of England to set the short-term interest rate and to forecast inflation,” says John Redwood, a veteran Conservative MP and former cabinet minister.

“But nor should anyone challenge the right of Government and parliament to set fiscal policy. If the Bank persists in selling bonds at big losses, it preempts crucial money needed for other purposes.”

Does it have to be this way? The short answer is: no.

“QE and QT is not a Bank of England independent policy – it is a joint policy with the Treasury,” says Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg, a former business secretary.

“No other central bank is doing it in this way, so it could be done differently at lower cost.”

The Federal Reserve has taken a very different approach. The US central bank effectively registers a loss and promises to pay it off over time, rather than charging it immediately to the taxpayer.

The Fed can do this because it has more income streams than the Bank.

Most notably, it keeps the income from seigniorage – the profit made from printing banknotes. Andrew Bailey last week pointed out that Britain does not have the same setup.

“This option is not available to us here in the United Kingdom. Courtesy of the 1844 Bank Charter Act, and following the Currency and Banknotes Act of 1928, all seigniorage income generated by the Bank’s Issue Department is paid directly to HM Treasury,” the Governor said.

“At the current rate, this is around £4bn per year. So neither have we retained the positive cash balances in the APF as they accumulated when Bank Rate was low, nor do we have access to a future income stream, against which we could off-set negative cashflows in the future in the way that other central banks are approaching it.”

Of course, Parliament can change the laws that the Governor references. It could let the Bank keep the £4bn a year from printing banknotes to pay off the losses on QE.

The process would be slow – it would take more than quarter of a century to cover the net loss of £106bn.

But at least it would represent a predictable loss of income for the Treasury, rather than risk the large and unpredictable costs of the current regime.

If following the Fed is not an option, Britain could copy the European Central Bank (ECB).

The ECB holds on to the bonds it purchased until they mature, meaning it receives the full face value of the bonds.

By contrast, the Bank of England is actively selling some of its bonds. When interest rates rise, the market price of bonds falls.

The Bank bought when rates were low and is now selling at a loss.

Another difference is how the Bank and the ECB treat the new money they created to buy those bonds.

The ECB pays less interest to commercial banks on the reserves they hold at the central bank.

It pays nothing on the portion of reserves lenders are compelled to hold by regulations, only giving them a return on the money which they hold over and above that minimum level, in a process known as tiering.

By contrast the Bank of England pays its base rate – 5.25pc – on all reserves, which is more than it receives in income on the bonds in its QE portfolio.

Reform, the party headed by Nigel Farage, wants to scrap these payments to commercial banks.

The party’s draft manifesto says that in the first 100 days of the next government, the “Bank of England must stop paying interest to commercial banks on QE reserves”.

“Other central banks are not doing this. Senior economists and a former deputy governor of the Bank of England agree. This saves £30-40bn per year,” Reform says.

Redwood argues that since the Bank only started paying interest on reserves at all in 2006, it should not be unimaginable to reverse that decision, at least in part.

“The Bank of England should study carefully how the European Central Bank is controlling the losses much better. There is no need to sell bonds into the market on big losses,” he says.

“And you can manage the rate of interest you pay on deposits, as the ECB has done and as the Bank of England used to do.”

Bailey has argued the ECB’s regulations work differently. But politicians are growing increasingly impatient.

Ultimately the costs of QE – which successive chancellors, both Labour and Conservative, promised to pay – cannot be magicked away. Someone must pay.

Cutting payments to banks effectively represents a new tax on the City. Letting the Bank of England keep seigniorage income is a loss of a long-established income stream to the Treasury.

However, moving to a Fed or ECB-style system would loosen the fiscal straitjacket on the Government and potentially free up billions.

The Conservatives have so far shown little inclination to change the rules, and it is understood Labour has no such plan either.

It might prove easier to change the borrowing rules to lessen the immediate strain, though so far Reeves has promised only to toughen them up.

On current form, Threadneedle Street will be a drain on the public purse in the years ahead.

This article was first published on May 30. It was updated on June 10 to reflect proposals made by Reform UK

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance