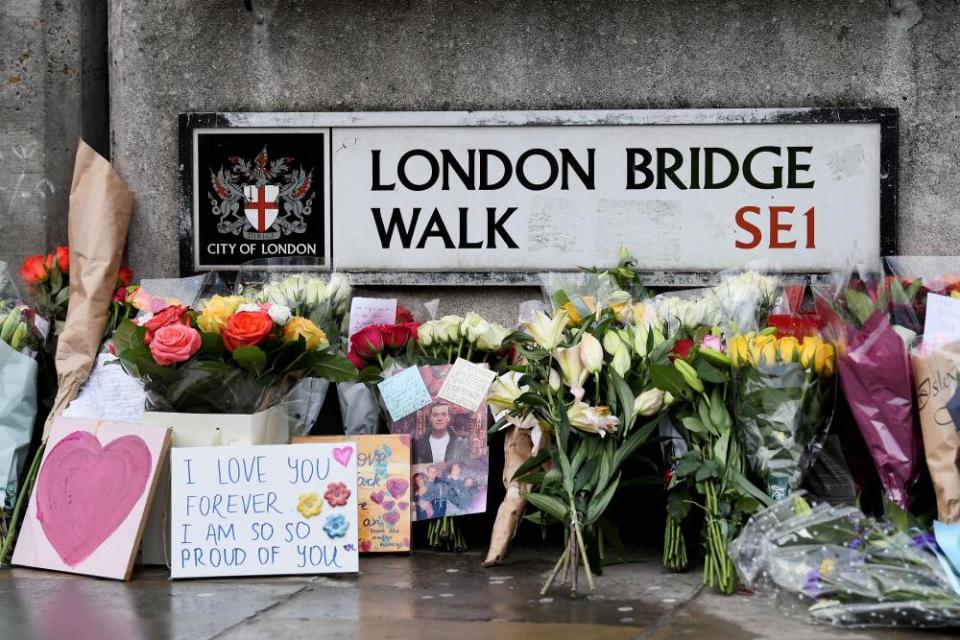

London Bridge attack, one year on: ‘Jack's story jolted people – we have to keep that going'

Dave and Anne Merritt weren’t sure how to mark today’s anniversary of the murder of their beloved son Jack. Milestone days are always the hardest. Unlike the day that would have been his 26th birthday, at the beginning of October, when they and their younger son Joe and Jack’s girlfriend, Leanne O’Brien, went for a long walk at one of his favourite places on the Suffolk coast, there are no good memories associated with 29 November. But still, Dave told me a week ago, with typical resolve: “We do want to try to somehow confront it.”

Jack, he says, was always making stuff: music, art, food. So they are inviting people to join in today with “Creating with Jack Merritt”, “whether that’s painting a picture or making up a new cocktail or doing a bit of creative writing”. The plan is to share the collective results on Instagram. “We don’t want to just spend the day thinking about the day,” Dave says. “I’m sure it will be very upsetting. But it’ll be as good a day as we can make it.”

The bar for that creativity has been set by Rosca Onya, one of the many friends Jack met through his inspiring work as course co-ordinator at the Cambridge University prison initiative Learning Together. Onya was supposed to have been at event at Fishmongers’ Hall by London Bridge, to mark the five-year anniversary of Learning Together, at which Jack and Saskia Jones, 23, a Cambridge graduate volunteer on the programme, were both fatally stabbed by 28-year-old convicted terrorist Usman Khan, who was among the ex-offenders who were attending that day.

Onya last week released a video of the rap he has written in Jack’s memory. His own traumatic story is typical of the lives that Jack and Saskia touched and helped to save. Onya grew up in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; displaced by war, from the age of four he spent most of his childhood in refugee camps, separated from his parents. He witnessed the death of his brother and lost his sister. When he came to London, unable to speak English, he was bullied at school, sought belonging in a gang and was convicted aged 18 on a firearms possession charge and given an indeterminate sentence, an IPP (imprisonment for public protection). Learning Together, the pioneering programme on which Cambridge criminology MA students were taught one day a week on equal terms alongside inmates at the “therapeutic” HMP Grendon, was the crucial step in his learning how to talk about his experiences.

He credits Jack with guiding him toward that life-saving openness. Jack was a big physical presence, Onya says, but also had a vulnerability that he wasn’t afraid to show. To begin with, he and Jack bonded over their shared love of music. “We were always planning music in which I could talk about my experiences, but tried to help spread joy at the same time,” Onya says. “To reinforce that mindset that says, just because your life took you to various difficult directions, that doesn’t have to be the end of your story.” Onya’s tale is not over. He is out of prison, but the terms of his IPP sentence prevent him from working to help care for his son. He has a criminology qualification from Cambridge, and is planning a degree course, but there are moves to have him deported back to the DRC, where he has not been since he was four.

Without his “brother” Jack, he has become close to the Merritt family (Dave appears in a dialogue in the music video, addressed as Dad). “Knowing Dave and Anne, you see how Jack became who he was,” Onya says. “Any time that he invited me to go to Cambridge to chill with him or if we did public speaking together, that’s all he ever instilled in me: he just wanted me to be the best version of myself.”

Onya’s heartbreaking track also surfaces the hardest questions that attended the tragic killings a year ago. Particularly those raised by that worldwide front-page tableau that showed Khan, apparently wearing a suicide vest, courageously confronted on London Bridge by a small group of men – one armed with a narwhal tusk taken from the wall of Fishmongers’ Hall – before he was shot and killed by the police.

To begin with, those images were presented as a fight between good and evil, terrorist versus have-a-go heroes. As more details of those who confronted Khan emerged however – the fact that nearly all of those who risked their lives to save others were also ex-offenders, two of them murderers – that story became more complex. In retrospect, that surreal scene looks a lot like battle between one idea of human nature – the belief that people who do terrible things can be redeemed with the right support – and another that says no, there can be no redemption. There have been far too many terrorist killings, but never one that required each of us to confront our fundamental ideas of humanity quite so starkly.

Laura Suggitt has thought a lot about what that scene meant. She met Jack on the first day of the Cambridge University criminology MA and after that, she and Jack and her boyfriend, Lewis Taylor, became an inseparable trio. They all were part of the Learning Together course and when Jack stayed on to work on it, she and Taylor went on to jobs at the Ministry of Justice. “Believe it or not,” she says, “even though they know that you’ve experienced this loss, people still say directly to me, ‘Well it was inevitable, wasn’t it?’ or, ‘It was always going to end like that’”, implying that any efforts to rehabilitate violent criminals were naive and doomed to failure.

“And you know, I strongly, strongly dispute all of it,” Suggitt insists. “Because, as Jack would say, any life in which you don’t believe in second chances is no life at all.”

For the three of them, working alongside the prisoners at Grendon was a truly transformative experience. “I certainly didn’t think of myself as somebody that had preconceptions,” Suggitt says. “And then I turned up and realised I definitely did.” What struck her, and everyone else I’ve spoken to about the course, the aim of which was strictly education, not rehabilitation, was that “even when people had come from these totally different backgrounds, you really felt this commonality. It was incredible.”

In her current job at the MoJ Suggitt works a lot with prison statistics. She sees the stats on incarceration and those on reoffending and knows that in the UK both are stubbornly the highest in Europe. She knows that programmes such as Learning Together aren’t a simple solution to that, but that they point towards a different way. The stats bear it out. “I look at that room [at Fishmongers’ Hall] and I think, well, there are hundreds of people that have gone through that programme, now across the country, who have battled to get a second chance. And many of them are the kindest, most supportive people that I have ever met. And there is one person who did this terrible thing. Hundreds against one. So I think, even in that sense, the numbers don’t lie.”

The process of making that argument – that the murders of Jack Merritt and Saskia Jones should shine a light much more on hope of redemption than on the despair of terrorism – began the day after the tragic events on the bridge. Dave Merritt has the bravery to look back on that day a year ago in all its details. How he and Anne were called down to London first without knowledge of what had happened and then had to wait at the hospital for several hours while there was a drawn-out process of identification, before driving back to Cambridge to tell Joe, home for Christmas from his last year of an engineering degree at Bristol.

The last thing the police family liaison officer told them that night was “don’t go on social media, don’t put Jack’s name out there. Because if you do, the media will just descend on you.”

There is, as Dave knows only too well, no single model for grief. Saskia Jones, a young woman with no less fierce promise and humanity than Jack, was also killed that day. Her family and friends mostly followed that police advice, advice that 99% of us might have stuck with, and defended their right to grieve in private. Dave went to bed thinking he would do that too.

“I woke up quite early,” he recalls, of the following morning. “I get up early anyway” – he’s the estate manager at the sixth-form college in Cambridge that Jack and Joe both attended – “and I looked at my phone.” On Twitter he saw the narrative that was starting to take shape. It was the week before that most fevered of general elections and Tory voices were already using the terror attack to argue for more draconian policing and sentencing.

Reading that, Dave says: “I just thought I can’t sit here and say nothing, because all that was so opposed to what Jack believed in. And so I did a couple of tweets, just to say, don’t use this in an opportunistic way.”

Inevitably, by the following morning, Boris Johnson had done just that, writing an article in the Mail on Sunday headlined “Give me a majority and I’ll keep you safe from terror”, arguing that not only terrorists, but all violent offenders should be kept in jail far longer in an end to the automatic early release system.

“Of course,” Dave says, “Johnson couldn’t believe that this gift had fallen into his lap, with a leader of the opposition who he could label as soft on terrorism.” It still angers him that the prime minister shamelessly used his son’s death in that electioneering without even having the grace to contact the family, then or since. “Never a letter or an email or a phone call.”

That first morning, Dave went back to bed and Anne asked: “You’ve not been tweeting, have you?” The police were right, the media did descend on them for a while. “But if you ask Anne now she is really glad that I did it,” Dave says, “because it started to pull things back in the right direction.”

That sentiment, that determination that Jack’s work not be taken in vain by politicians, was shared by another of Jack’s closest friends, Laura Suggitt’s boyfriend, Lewis Taylor. From the moment he first saw Jack – hungover, two loop earings, white T-shirt in a sea of earnest Cambridge corduroy – he knew they were destined to be mates. That friendship was characterised not only by Learning Together but also by long after-club nights drinking whisky, taking turns with the playlist and putting the criminal justice system in order.

Taylor happened to be away in Budapest when he heard the news about Jack at six o’clock in the morning. He got a flight home “just crying all the way”. One of his immediate thoughts was that he knew “exactly what was going to happen politically with this”. The next day, he and Laura sat at the breakfast table and wrote the bones of an article that imagined what Jack would have thought of it all and took it over to Dave and Anne’s where they all worked on it some more. “Jack loved the Guardian, so we thought we should send it there.”

In the article, printed on the front page, which quickly became among the most widely shared pieces in the paper’s history, they wrote: “Jack would be seething at his death, and his life, being used to perpetuate an agenda of hate that he gave his everything fighting against… What Jack would want from this is for all of us to walk through the door he has booted down, in his black Doc Martens.” It continued: “That door opens up a world where we do not give indeterminate sentences… Where we do not slash prison budgets and where we focus on rehabilitation, not revenge. Jack believed in the inherent goodness of humanity and felt a deep social responsibility to protect that. Through us all, Jack marches on.”

The article ended with a crowdfunded appeal for a proper celebration of Jack’s life. Taylor took a month off work to organise that memorial service. He persuaded ancient Great St Mary’s church in Cambridge to stage the funeral – the only other one held there in modern times had been for Stephen Hawking – allowing a thousand people to come with many more outside. It was Laura’s idea to ask Nick Cave, always the Merritts’ “family favourite”, to play at the service. Cave had also lost a son. As soon as she managed to get an email to him he was on her mobile phone saying he was going to come from Australia to do it. She has lots of memories of that day, but the one she treasures most was seeing Cave and his wife sit with Anne and Dave before the funeral at the church.

Dave sent me one of the memorial booklets that they had produced for the ceremony. Jack’s big grin smiles out from every page – among tributes from lawyer friends from Manchester University (from where he gained an effortless first) and shared memories and funny stories from school mates and housemates, as well as eulogies from colleagues. The rapper Dave, whose brother had been on the Learning Together programme in Grendon, not only dedicated his Brit award to Jack but performed a set at the memorial party alongside Onya. “For a funeral,” Dave says, “it couldn’t have been any better. Jack’s friends just wrapped us up and supported us.”

Of course, after that, complicated life returned. Plans for events and campaigns that might have built on those stories of Jack’s work were partly put on hold by Covid. Before the killings, 600 people were on Learning Together programmes across the country – 300 from university and 300 from prisons – but that was paused for a while, to reflect on what had happened. By the spring, and the planned restart, the country was in lockdown, so most of that effort has obviously been online

Dr Amy Ludlow and Dr Ruth Armstrong, who created Learning Together, have agreed not to comment at all on what happened at Fishmongers’ Hall until next year’s inquest. In June, they published an academic article that examined the evolution of the programme itself, without reference to the events of last year. The piece gave an insight into the way that Learning Together developed the idea, that “as an ‘us’ we had potential”.

That “us” implied a move away from “individualised notions of responsibility for past failures and future successes”, the double bind of the criminal justice system and higher education. “In place of scholarly detachment and distance, we found that PAR (participatory action research) dragged us into reciprocal relationships of solidarity, towards what our colleague Max Harris has called ‘a politics of love’.”

There are plenty of success stories to which those politics can refer. One is Steve Gallant, the man who wielded the narwhal tusk on the bridge, whose life sentence for murder was reduced in a rare Queen’s pardon in September, a decision welcomed even by the family of the man Gallant was convicced of killing 15 years ago. Another is Marc Conway, who had been due to deliver to deliver a speech that afternoon at Fishmongers’ Hall and who was among those who chased the killer up on to the bridge and alerted the police.

Conway grew up nearly opposite Belmarsh prison and, having dropped out of school aged 13 was in and out of it and other institutions for 20 years. Just past his 30th birthday he was given an IPP sentence of five years. “You hear of people on them who are sentenced to 28 days and are still in prison 12 years later,” he says. “I thought my life was over.”

Before Learning Together, he imagines that the only other time he had come into contact with people from Cambridge University was when he was in the dock. “I thought they would pull up with chauffeur-driven cars, but within five minutes that was dispelled.” He describes the course as “giving him for the first time in my life a way of articulating what I had never been able to articulate – I can’t begin to tell you how that felt. It brought this little ray of hope into an environment where there wasn’t a lot of hope.”

Conway became a mentor and then a facilitator for one of the groups, a role usually done by a PhD student. Now 38, five years on, he is well into an Open University degree in criminology and psychology and, out of prison, working full time as a policy officer at the Prison Reform Trust, sometimes sitting in meetings alongside government ministers and senior civil servants.

Jack Merritt was instrumental in all of that, he says. “The thing was, we all knew Jack could have walked into some big job somewhere, he had a masters from Cambridge, and he had this great warmth, but he chose to work with us. He always, always made time for you.” Jack looked out for Conway when he was first released and experienced the terror of “being alone in silence for the first time in years”; he wrote him a reference for the Prison Reform Trust job, “and then the first day I went into work he rang me in the morning just to say good luck and that he was there if I needed to talk. He believed in it all so much.”

Though IPPs were abolished in 2012 Conway, along with thousands of others, remains on a 99-year licence under its terms. He was “over the moon” when he heard about Gallant’s pardon. “It reminds people that though people may have been offenders that does not mean that is who they are for the rest of their life.”

It is of course one thing to believe in rehabilitation in the abstract, but quite another to hold on to that faith when you have witnessed the absolute worst that people can do.

For Lewis Taylor, at the sharp end of policy, that is not only an emotional faith but a pragmatic one. “We know that in almost all cases something terrible has happened to [violent offenders] as children and the only real way to combat that is to care more. Whichever way you look at it, if you just lock those people up they are going to come out worse.”

When he thinks back a year, the day “boils down to just disbelief really. It is like biblical. These people have been given up by everyone. And suddenly, Jack, this shining light, comes into their lives. And it is that person who gets killed. You can’t write how sad that is.” The thing that helps to keep him believing is that it was “uniting energy” that was released by the tragedy, not the opposite. Jack’s story “jolted people’s consciousness – we have to keep that going”.

Dave Merritt wasn’t certain that he would maintain his faith in that uniting energy, but that is how it has turned out. He talked a lot with Jack about the ethics and efficacy of indeterminate and whole-life sentences and was mostly persuaded of his son’s view that “they were never effective and almost never justified”. He makes an exception for terrorist offences, “which are clearly a different category”, but in spite of all this year has thrown at him maintains the belief set out in his Guardian article.

That is not to say that he in any way excuses his son’s killer. On Thursday of last week the Merritt family launched a legal case against the government aimed to ensure that the relevant authorities take full responsibility for any failures in managing Usman Khan after his early release from prison on license in 2018. The legal case is designed to reinforce the efforts of next year’s inquest in answering the critical question of how Khan came to be cleared to attend the Learning Together event at Fishmonger’s Hall. Speaking to Dave Merritt about the inquest, I wonder if it is possible for him not to be filled with anger toward Khan.

“No, I do feel angry,” he says, “though it’s hard to feel angry with someone who is dead. I just think it’s a complete and utter waste. Of his life, but also to take the lives of two exceptional people who were doing good. You know, that’s the thing about Jack – and Saskia – they were the definition of ‘do-gooders’. That’s one of the things that made them special.”

Artwork and writing in memory of Jack will be on Instagram: #creatingwithJackMerritt. To download Rosca Onya’s track “Jack” go to roscasworld.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance