London’s disastrous road and the world’s most expensive megaproject fails

The most ill-fated construction ventures of all time

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Megaprojects are mind-bogglingly complex undertakings that are typically vulnerable to skyrocketing costs and endless delays. However, for many of these projects, running over schedule or blowing budgets were the least of the worries of those charged with delivering them.

Read on to discover the large-scale ventures worth billions, including London's Ringways road system, that went horribly wrong.

All dollar amounts in US dollars unless otherwise stated.

Hallandsås Rail Tunnel, Sweden

Skanska

Construction of the 5.4 mile-long (8.6km) Hallandsås Rail Tunnel (also known as Scanlink) in southwestern Sweden began in 1992 and was expected to have been fully completed by 1995. But almost from the beginning, groundwater began seeping into the tunnel excavation, presenting massive problems for the tunnel boring machine. The contractor switched to a more conventional drill and blast method, but after mining only 1.8 miles (3km) of tunnel, they abandoned the project.

Hallandsås Rail Tunnel, Sweden

Skanska

Construction titan Skansa took over in 1996 but faced the same problem with water seepage, and opted to use a substance called Rhoca-Gil to seal cracks in the rock. The solution proved not only to be ineffective but also toxic, with the sealant poisoning fish and cattle in the vicinity. Work was halted in 1997 and didn't resume again until 2005 after thorough decontamination. The tunnel was completed in 2015, 23 years behind schedule and hugely over budget, costing a total of $1.3 billion, around $1.7 billion (£1.4bn) in today's money.

Superconducting Supercollider, USA

www.indico.cern.ch

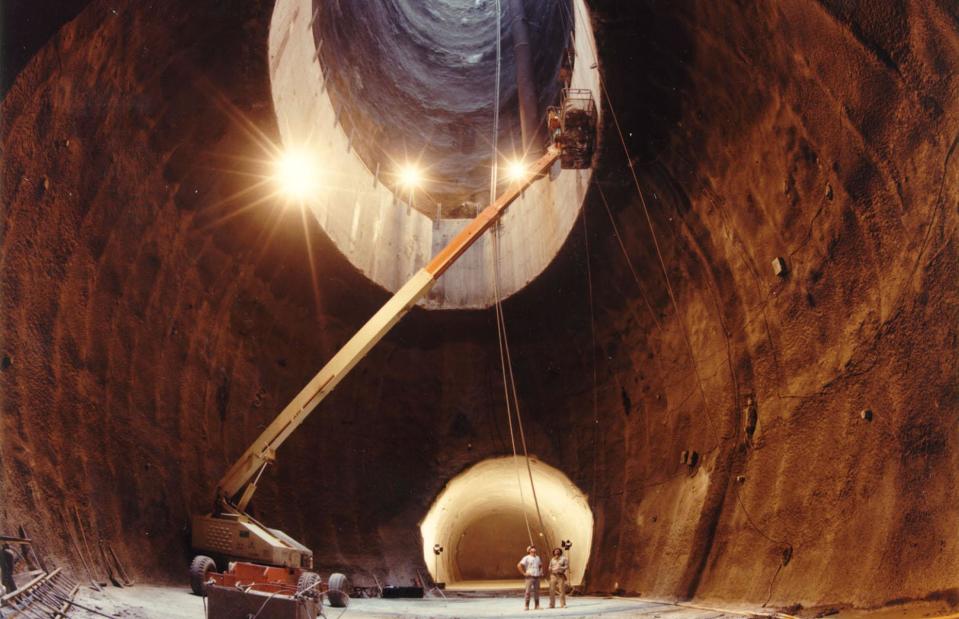

Nicknamed “the Desertron”, the Superconducting Supercollider (SSC) was a proposed particle accelerator complex in Texas that would have been the most powerful in the world and America's answer to the famous Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland, which was eventually completed in 2008. Preliminary work on the SSC began in the late 1980s, and by the early 1990s around 15 miles (24km) of tunnels were bored, and 17 shafts sunk on the site.

Superconducting Supercollider, USA

Magnus Manske, via Wikimedia Commons

However, facing surging costs and a failure to secure international funding, US Congress finally pulled the plug on the project in October 1993. The budget had ballooned from $4.4 billion to more than $11 billion, a staggering $23bn (£19bn) in today's money, with US taxpayers footing a significant proportion of the bill. Unsurprisingly the megaproject was deemed to have been grossly mismanaged.

A chemical company eventually purchased the abandoned facility, reopening it for operations in 2013 after a year-long renovation.

World Islands, Dubai

AFP/Getty

Dubbed “Dubai's ultimate folly” by Guardian journalist Oliver Wainwright, plans for the World Islands, an artificial archipelago, were unveiled to much fanfare in May 2003. Work began that same year on the 300 artificial islands off the coast of the Emirate but came grinding to a halt in 2008 due to the global financial crisis and the collapse of the Dubai property market. Investors found themselves seriously out of pocket on the $14 billion project, a hefty $20 billion (£16.5bn) in 2023 money.

World Islands, Dubai

ABACA/PA

The owner of the Great Britain Island was jailed for fraud, while Ireland's proprietor took his own life. In 2009, reports suggested several islands were sinking into the sea. Lebanon was the only developed island until construction began in 2020 on the $5 billion (£4.1bn) Heart of Europe, a six-island development connected by bridges and helicopter routes. Developers had expected the first hotels to open in 2023, with a final completion date set for 2026. Yet most islands remain untouched, and doubts persist over whether the entire megaproject will ever be completed.

American Dream Meadowlands Mall, USA

![<p>NHRHS2010 [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/i08szLFoKPrsGaIV5DCxPQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/75e1d170c4ae99b8c9eaab96b1b7c8bf)

NHRHS2010 [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

The World Islands wasn't the only major development to run aground during the global financial crisis of 2008. First proposed back in 2002, the American Dream Meadowlands Mall in New Jersey (formerly known as the Xanadu project) has turned into an American nightmare. Beset by everything from investor bankruptcies and legal challenges to ballooning costs and construction delays, the sprawling retail and entertainment complex ended up costing $6 billion (£4.9bn) in today's money. It was initially slated to open in 2007, with an estimated construction price tag of $1.2 billion.

American Dream Meadowlands Mall, USA

![<p>Brad Miller Millertime83 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/Ns0PDfqR3ABJS19V_Ztt3w--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/56ec5b158586e6b4e7d8b297ece38653)

Brad Miller Millertime83 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

Construction of the New Jersey mall began in March 2005, but the opening date was pushed back and the mall's parent company went bust in 2007. A slew of poorly executed hand-offs, bankruptcies, litigation, and countless other issues, including the partial collapse of the roof, further delayed the megaproject. It finally opened its doors in 2019, just months before the pandemic hit, and a shocking 13 years behind schedule.

Now fully open, the American Dream Mall isn't doing well. In 2022, its losses quadrupled to $245 million (£200m) as it struggled to attract tenants and customer traffic declined.

Berlin Brandenburg Airport, Germany

Ralf Hirschberger/AFP/Getty

Planning for a new airport for Berlin started in 1989 following the city's reunification, but the megaproject wasn't approved until 2006. Construction began that same year, and the airport was poised to open in October 2011. It was expected to cost €2.4 billion ($2.6bn/£2bn), but the budget and scheduled completion date proved to be very wishful thinking. By 2010, one of the main contractors had gone bust, and the opening date was pushed back to June 2012.

Berlin Brandenburg Airport, Germany

peter jesche/Shutterstock

A mere six months before this anticipated grand opening, it was revealed that the airport's unconventional fire system had failed. The deadline moved again, and an embarrassing catalogue of errors followed, including incorrectly sized escalators and monitors that burned out after years of displaying info despite the airport's lack of passengers.

Not surprisingly, the errors and delays blew the budget to more than €7 billion ($7.5bn/£6.8bn) by the time the airport opened in October 2020, a painful $8.9 billion (£7.4m) in today's money. In the years since many have criticised the failures of an airport designed nearly 20 years ago to meet the needs of today's travellers.

Ciudad Real Central Airport, Spain

Oli Scarff/Getty

A monument to the hubris that characterised Spain's pre-financial crisis spending spree, Ciudad Real Central Airport was marred by poor planning from the outset. Originally envisaged as an overflow airport for Madrid, the so-called 'central' airport was ironically built in the middle of nowhere, 141 miles (225km) away from the Spanish capital. By the time it opened in 2009 it was estimated to have cost €1 billion, that's around $1.9 billion (£1.5bn) today.

Ciudad Real Central Airport, Spain

Oli Scarff/Getty

It was hoped that the airport would handle up to 10 million passengers a year, but it attracted just two low-cost airlines and several thousand travellers in the first 12 months. In 2012, the airport's owner went bust and all operations ceased. The site was eventually sold in 2015 to a Chinese-led consortium of investors for a measly €10,000, 100,000 times less than it cost to build.

Three years later, it was sold for €56.2 million to Ciudad Real International Airport SL. After a failed rebranding as 'Madrid Airport South', it became known as a ghost airport. However, many airlines took advantage of the white elephant as a space to store jets out of service during the pandemic.

Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Generating Station Units 2 and 3, USA

DJSlawSlaw / Wikimedia Commons

A similar story of abandonment has unfolded in South Carolina, USA. In 2008, local utility companies partnered with the Westinghouse Electric Company to build two AP1000 nuclear reactors at South Carolina's Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Generating Station. Construction on the reactors began in 2013, with a view to having them operational by 2018.

Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Generating Station Units 2 and 3, USA

Dennis Corporation

Fabrication delays put back the megaproject's completion date to 2020, and costs soared. As a consequence, Westinghouse filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in March 2017, and the megaproject was eventually abandoned. However, documents later released to the public showed mismanagement of the project long before 2017.

In total, $9 billion was wasted on the reactors that will never run, a jaw-dropping $11.3 billion (£9.4bn) in today's money.

San Francisco Shipyard, USA

Courtesy Lennar Corp/Five Point

The largest redevelopment project in the city since the 1906 earthquake, the San Francisco Shipyard revamp is set to boast 12,000 relatively affordable homes and an array of shops, offices, restaurants, and green spaces. Scheduled for completion sometime during the early 2030s, the waterfront development is set to cost $8 billion (£6.5bn). Construction started in 2013 for phase one of the community, and buyers are already moving into some of the completed homes.

San Francisco Shipyard, USA

Google Earth

However, in 2018, several national lenders refused to provide mortgages on Shipyard properties due to uncertainty over contamination levels. One part of the development is next to land previously used as a covert nuclear testing facility by the US military and has shown dangerous levels of contamination. The company in charge of the clean-up is alleged to have faked the soil tests that deemed the site toxin-free, while the US Navy has been accused of a cover-up. Both are battling lawsuits related to the site.

Property developer Lennar is still selling homes at the Shipyard development with prices as high as $1.2 million (£992k) for a three-bedroom townhouse.

Muskrat Falls/Lower Churchill Project, Canada

Nalcor Energy

One of Canada's most controversial megaprojects, this enormous hydroelectricity venture in Labrador and Newfoundland has been nothing but trouble since construction began in 2013. Billed as an affordable and environmentally friendly way to meet the energy needs of the two provinces, the megaproject has proven to be a disaster. Poor planning, botched engineering, and other issues have pushed the scheme well over time and budget.

Muskrat Falls/Lower Churchill Project, Canada

Nalcor Energy

One of the project's biggest mishaps came from its largest bid package. Under a CAD$1 billion contract, the company tasked with building the facility’s powerhouse and other concrete structures in late 2013 had little experience working in the region. Hoping to work through the harsh winter conditions, the firm attempted to build a heated dome enclosing the worksite, allowing it to pour concrete year-round. The dome idea was abandoned halfway through its construction and dismantled, and the contractor was removed from the project.

The project finally reached completion in 2021, almost CAD$6 billion over budget, with a final price tag of around CAD$13.4 billion. That's approximately $10.8 billion (£8.8bn) in today's money.

Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement tunnel, USA

![<p>Seattle City Council from Seattle [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/f920en_xf3Grb6eX96xpVw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/lovemoney_uk_264/e3d4f88640d25be9a676a6d5efefbc16)

Seattle City Council from Seattle [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Construction of Seattle's Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement tunnel began in July 2013, and planners were confident the vast project would be done and dusted by December 2015. If only. In December 2013, the colossal tunnel boring machine Big Bertha, at the time the largest in the world, came to a grinding halt.

Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement tunnel, USA

Brierly Associates

Tunnelling for the megaproject stalled for two years so a shaft could be excavated to allow for repairs to the machine's main bearing. The tunnel finally opened to traffic in February 2019, three years and two months behind schedule and close to $1 billion over budget. Its final price tag was estimated to be $3.3 billion, around $4.1 billion (£3.4bn) in today's money.

Unfortunately, financial models released this spring predict the tunnel will not be able to sustain itself, with up to 30% reductions in expected revenue over the long term.

Ottawa Light Rail, Canada

Chris Roussakis/AFP via Getty Images

An unexpected hole in the ground scuppered another North American tunnel project, this time in Ontario, Canada. In 2013, construction started on Ottawa’s 18-mile-long (27km) light rail line, including tunnels through the city’s downtown area. Over the last decade, the megaproject has faced seemingly endless problems. The biggest debacle happened in June 2016 when a large portion of Rideau Street caved in during tunnel construction, causing a massive sinkhole that knocked out power to the majority of the downtown area, caused a gas leak, and forced the evacuation of all nearby businesses. Unfortunately, that wasn't the last disaster to plague the project.

Ottawa Light Rail, Canada

Transportation Safety Board of Canada

The line went into operation in 2019, only a year behind schedule, but passengers endured long delays and mechanical issues in its first year of service. But the worst was yet to come. In August and September 2021, two separate trains derailed while in service. Investigations found issues with the trains' wheels and reports earlier this year suggest the design still poses a risk.

The project is estimated to have cost CAD$9 billion, around $7.6 billion (£6.3bn) in today's money.

Ryugyong Hotel, North Korea

Annaj77/Shutterstock

It was meant to be a symbol of prosperity, but has ended up as anything but. Looming ominously over the North Korean capital, Pyongyang's pyramid-shaped Ryugyong Hotel remains unfinished and unoccupied. Construction of the 105-storey skyscraper, which stands 1,080ft (330m) tall, began way back in 1987 but ceased in 1992 when funds dried up during the period of economic crisis that followed the breakdown of the Soviet Union.

Ryugyong Hotel, North Korea

Ed Jones/AFP/Getty

Work resumed on the billion-dollar “Hotel of Doom” in 2008 but only the exterior glasswork was finished. Construction halted yet again with some commentators suggesting that North Korea lacked the raw materials and expertise to complete the structure, but access roads were built in 2017 and LED displays were added to the building. Nevertheless, the hotel remains empty and it appears it will stay that way for the foreseeable future. Estimates peg the total construction costs of the hotel to date at around the $2 billion ($1.6bn) mark.

London Ringways

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

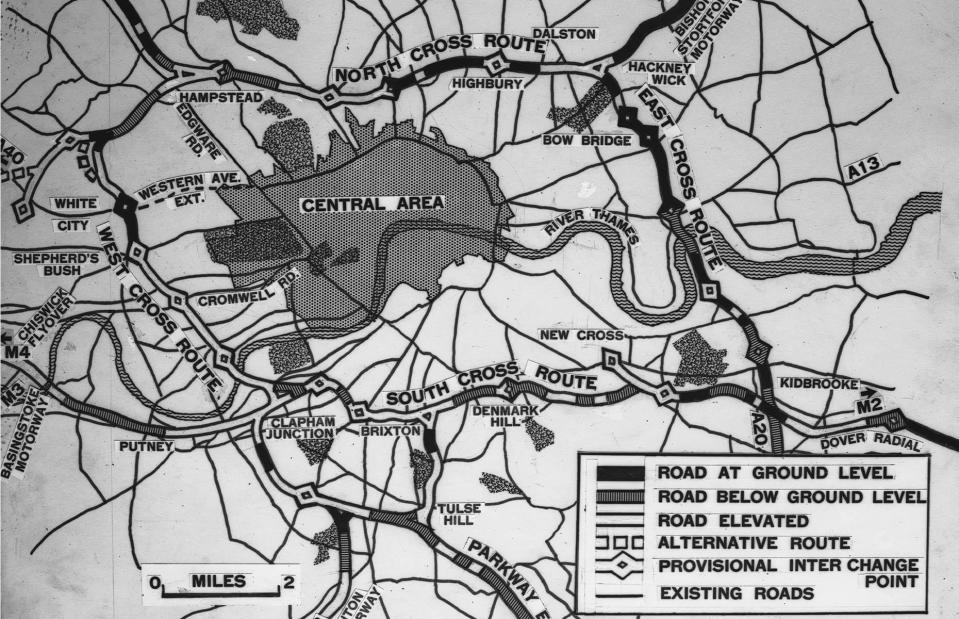

Plans for post-war London included building a network of roadways around the city and out into the suburbs. With the 1965 formation of the Greater London Council (GLC) the project evolved into the London Ringways, with the design scheduled for finalisation in 1969. Officially the project expected 20,000 households would be displaced by the new roads. However, opposition groups put the number closer to 100,000.

London Ringways

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 1970, the city opened the Westway elevated highway (pictured), to the protest of nearby residents. Not originally part of the Ringways, the new road caught the public’s imagination, and not in a good way. Adding to the troubles, the cost had grown to what would be an estimated £24 billion ($30bn) in today’s money. The Ringways project was abandoned in 1973, and the GLC was abolished little more than a decade later.

Now discover the over-budget and delayed megaprojects under construction around the world today

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance