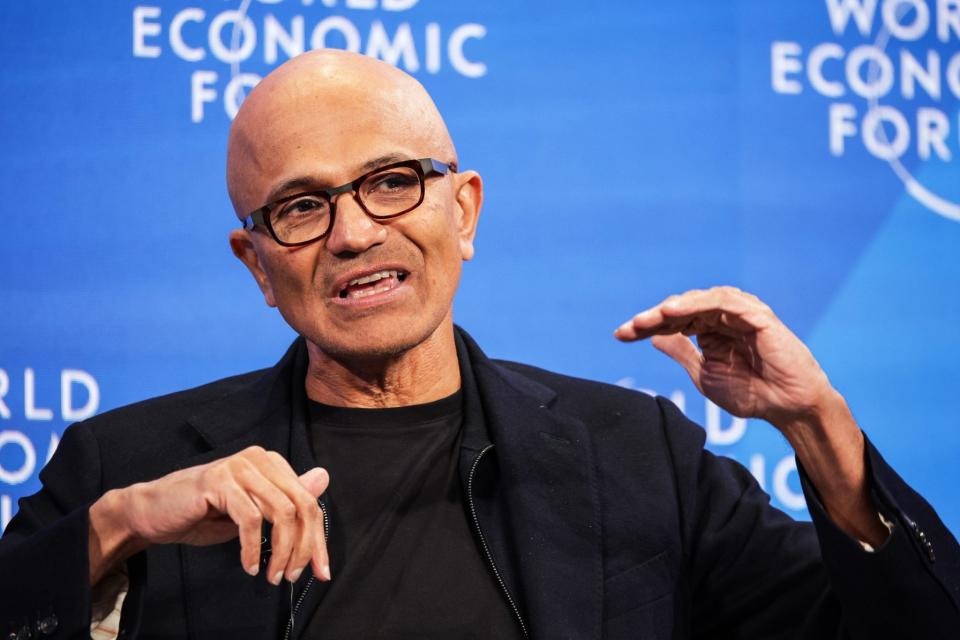

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella is an AI winner. He doesn’t like to talk about the potential losers

Hello and welcome to Eye on AI.

As everyone likes to point out, it is still early days for the generative AI revolution. But a few clear winners have emerged: Among the biggest is Microsoft, which, thanks to its partnership with OpenAI, has catapulted itself to the forefront of the AI boom. It also helps that most generative AI use cases complement Microsoft’s largely subscription-based business models rather than challenging them, as they do for Google’s ad-driven businesses. Microsoft’s stock price reflects this. Last week, the company edged past Apple to become the world’s most valuable public corporation, worth $2.875 trillion.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella will no doubt be the toast and envy of many of the CEOs and global bigwigs gathered in Davos, Switzerland, this week for the World Economic Forum, where “Artificial Intelligence as Driving Force for the Economy and Society” is one of the conference themes. En route to Davos, Nadella stopped off in the U.K. and I caught his fireside chat at London’s Chatham House yesterday. Somewhat unusually for Chatham House, the session was on the record, so I can fill you in.

Nadella is slick and polished. Much of what he said struck me as correct—but, perhaps unsurprising for a public company CEO, also only half the story. And, of course, the half Nadella presented was the bit most favorable to Microsoft. For example, he said that journalists should welcome AI tools that will help them write, never mentioning the profession’s concerns about both copyright infringement—for which the New York Times is currently suing Microsoft, along with OpenAI—and the idea that summarized news accounts produced by generative AI chatbots will rob news organizations of the revenue they need to survive.

On the topic of disinformation and the role it may play in elections this year, Nadella acknowledged that he was worried about it, but then said it should be policed at the point of “distribution”—in other words, regulators should crack down on the social media companies that allow disinformation to spread, not folks like Microsoft whose software might produce it in the first place. Comparing generative AI to word processing, he said, “It’s like anybody can write anything in a word processor. And then the only control human society has is how does that information get disseminated.” What he didn’t say is that there are plenty of other examples where society imposes restrictions on technologies at the point of production as well as at the point of distribution, like with guns and tobacco products.

When asked about fears that generative AI would kill jobs, Nadella said that one of the biggest problems that most developed economies face is lagging productivity growth. This has acted as a drag on overall economic growth. It has also made it difficult for labor to command wage increases without triggering inflation. And it has contributed to widening income inequality. Nadella said generative AI copilots such as the products (most of them branded “CoPilot”) that Microsoft is rolling out across its Office business software suite, will unleash a productivity boom. Increased labor productivity should make it easier for workers to capture a greater share of economic growth. So far, so good.

What’s more, Nadella said that some of these copilots would enable what he called “the frontline” workers in many industries to learn new skills and accomplish new tasks. He used the example of a British police officer he’d met on a previous visit to the U.K. who, although he had no coding skill, had used Microsoft’s PowerApps product to build a simple software application for his team at work. PowerApps has gotten even easier now thanks to generative AI, since users can specify the kind of application they want to build in natural language. Nadella then said “that means IT level wages can go to the frontline.” In other words, there’s a big gap between what skilled coders earn per hour and what a beat cop earns. But if the beat cop can now create apps, the cop’s wages should climb to be closer to what the programmer makes, he argues.

This also makes sense. For my forthcoming book on AI, I spoke to MIT economist David Autor and he essentially made this same point: Generative AI co-pilots might allow people who have been increasingly squeezed out of the middle class to rejoin it because it will allow them to take on some of the functions of higher-wage earners without needing the same qualifications that those professionals currently require.

But there are three big caveats here, conveniently none of which Nadella mentioned. The first is what happens to the wages of the average coder? Chances are, they will fall because now anyone can create an average software application. This is the “Uber effect”—when Uber let essentially anyone become a taxi driver, the earnings of licensed cabbies fell. For those already in highly skilled, highly paid professions, the distribution of earnings will become more barbell-shaped, with those at the very top of their field still able to command high earnings (and maybe even charge more because they will be providing a level of skill that AI copilots cannot match) while everyone else in the field sees their earnings fall as a whole crop of less skilled people competes to do those jobs with help from AI copilots.

It is even possible that AI copilots will make certain tasks accessible to so many types of workers that there will be no wage expansion at all. That’s the second caveat. This has actually happened before: Steam power was an incredible general-purpose technology that transformed economies and set off an unprecedented economic boom. Yet from 1790 until the late 1840s, workers’ wages in Britain, which was at the heart of the first Industrial Revolution, failed to budge, even as factory owners became enormously wealthy. Economic historian Richard Allen coined the term “Engel’s Pause”—named after Karl Marx’s good friend Friedrich Engels—to refer to this period of wage stagnation. Economists have debated the reasons for Engel’s Pause, but the leading theory is that early industrial factories depended on large quantities of unskilled and uneducated labor (in fact, many of these early factories employed lots of children). It was only in the second half of the 19th century when factory equipment became much more sophisticated and required more skill that workers’ wages began to rise rapidly. (Unionization and public education laws that required children to be in school also helped.) If AI copilots make it too easy for unskilled workers to replace skilled ones, it is possible wages will again stagnate.

A final point Nadella failed to mention is what happens to managers’ expectations and people’s workloads in a world of AI copilots. Past experience of office productivity software should tell us that it often eliminates a whole category of workers while making everyone else’s job just a little bit more difficult than before. A good example is what has happened in most companies with business travel. In the old days, companies would employ a travel agency to make arrangements for business trips. These days, most companies expect employees to book their own travel most of the time using online software. But this is often still a time-consuming task that employees must fit around their other work responsibilities, rather than simply handing it off to a specialist. The same may now happen with the task of building software or compiling and analyzing data—workers will now be expected to do it themselves, without any increase in pay or compensating reduction in primary responsibilities. So our jobs might just get a little bit more stressful and more miserable. Presumably, most police officers are police officers in part because they want to be police officers and not software developers. Now they will be expected to be both, whether they like it or not.

And with that, more AI news below.

Jeremy Kahn

jeremy.kahn@fortune.com

@jeremyakahn

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance