Reviving a Queen’s Heritage Brand in M&A Scene

MILAN — There’s one person who isn’t surprised by Schiaparelli’s upward trajectory and current heat: Arnaud de Lummen.

The curtain just fell over the brand’s fall couture show in Paris earlier this week, attracting the likes of Selma Blair, Doja Cat, Maria Sharapova and Kylie Jenner, and the founder of private investment company Luvanis pays tribute to Schiaparelli’s owner, Diego Della Valle, for abiding by one of the main requirements in bringing back a heritage brand: patience.

More from WWD

Dior's Peter Philips Prefers to Create Trends, Not Chase Them

'Fancy Dance' Newcomer Isabel Deroy-Olson on the Importance of Indigenous Storytelling

Behind the Scenes With 'The Fire Inside' Star Ryan Destiny Before the Dior Couture Show

De Lummen should know. He is himself a brand reviver, for example reintroducing Vionnet’s ready-to-wear in 2006 and then selling the label to Matteo Marzotto and Gianni Castiglioni three years later. Likewise, he revived the prestigious 19th-century trunk-maker Moynat and sold it to Groupe Arnault in 2010.

Acquiring heritage brands is a journey with potential pitfalls. Key steps necessary to avoid failure are “a long-term view that can span over decades, lots of research into trademarks, intellectual property, possible licenses and copyrights,” de Lummen said in a joint interview with Marco Consonni, partner at Milan-based legal studio Orsingher Ortu, which has worked with Luvanis for years to tackle these issues.

“You need experience, reviving a brand is a very long and complicated process and I would not encourage somebody to do it from scratch,” Consonni opined.

The current slower M&A scene may also discourage potential buyers. “I would not say there is a reluctance on the prices, but many acquisition projects are delayed or deferred,” de Lummen said. “But it’s not a general trend, the luxury industry is global and there are always some parts of the planet where things are slowing down and some parts of the planet where things are going well.

“We used to have a lot of requests and interest from Asia, which is still the case. But we see that potential buyers are more cautious about the assets, the quality of the brands, whether dormant, revived or already operating well. But we also speak regularly to institutions, distributors, investors based in the Middle East, and right now the activity that’s heavily around Dubai is very, very strong. Notably in the beauty industry, everything around perfumes, for instance,” de Lummen said.

The Middle East and Dubai, in particular, has become a home for Russians fleeing their country after the start of the war in Ukraine, leading to brisk business in the area, with stores brimming with customers and new restaurants opening, attracting investments, which may have otherwise been channeled into M&As, he continued. Wars and inflation impact activities and he added that “big conglomerates in Asia are now focusing on what they usually have in the basket. And they are a little bit more cautious about any new addition.”

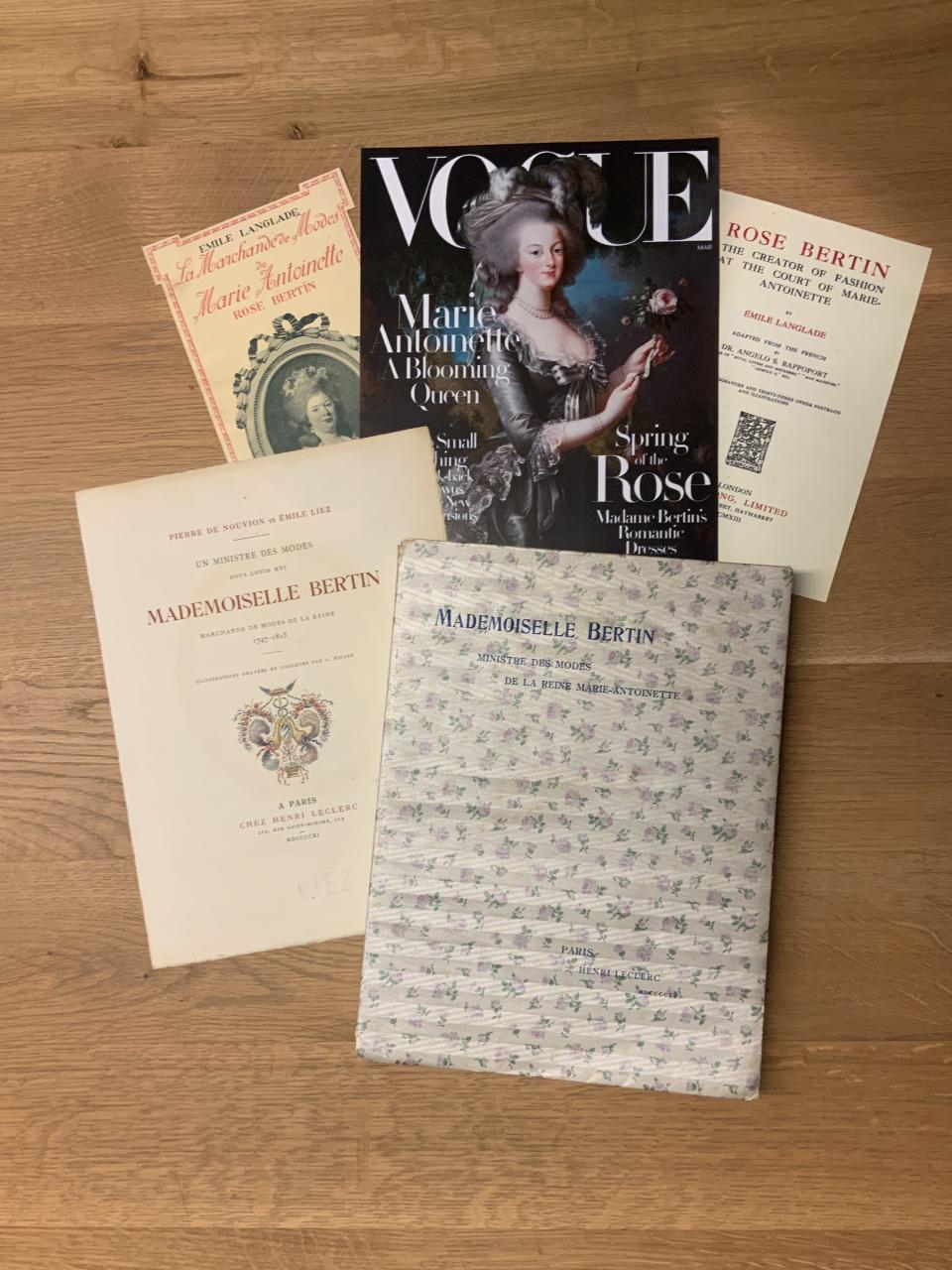

De Lummen revealed he is reviving a brand that has been in Luvanis’ portfolio for more than 10 years: Rose Bertin. The French designer and merchant was the favorite dressmaker of Queen Marie Antoinette for about 15 years and had a boutique in Paris, which was the “ancestor” of Colette, he explained. “She was the most well-known and celebrated fashion designer in Paris at the time, so much so that she was called the minister of fashion and she’s in all the history books.” Incidentally, he said a manga cartoon in her name was launched a few years ago and as the Rose Bertin mission in the game franchise “Assassin’s Creed Unity.”

“She chose the fragrances for the queen’s clothes, as dresses were perfumed at the time, so this is something we are launching within about a year,” he said, together with makeup products, while not disclosing the name of the partner in this new venture. Bertin also dressed the queens of Spain, Sweden and Portugal; Grand-Duchess Maria-Fedorovna of Russia, European aristocrats and celebrities of the time.

A “game changer” is taking place, and investors are looking at heritage brands also in the beauty world, as he sees a move from prestige brands to niche and ultra-high luxury, citing Creed, which dates back to 1760 and was acquired last year by Kering Beauté, as an example.

There is basically no marketing or advertising involved in communicating niche fragrances, conversely to prestige brands, he continued. “In perfumery, we’ve seen retail prices multiply by around three to five times and, of course, when you sell something at a higher price with less marketing, if you can tell a story about your brand, it’s better,” said de Lummen, adding that consumers have also been changing, “switching perfumes more often, and even when very young, they are willing to spend, so this sector is very dynamic.”

De Lummen said Shinsegae International, the South Korean fashion and luxury conglomerate that bought Paul Poiret, has legitimacy in focusing on the brand’s beauty, makeup and skin care, as the late Poiret was the first fashion designer to venture into perfumes.

While private equity funds are also eyeing the beauty industry, they are generally more cautious than in the past, said Consonni, and less interested in looking at heritage or luxury fashion brands, as their five- or six-year time frame of ownership will not be enough to revive storied labels.

“In the case of heritage brands, there are a number of intangible assets,” de Lummen said. Turning heritage brands into a business “is like giving a value to a painting or a work of art. Private equity funds or billionaires coming from outside the fashion world will value the numbers. You need to have faith, believe in the brands and have a long-term vision, looking into the future but also backward. I am sure that Rose Bertin will still be in the history books in 50 years and we will still talk about her.”

Reviving “sleeping beauties” can take 10 or more years, “if planets are aligned, which is why usually it’s really the industry leaders with a long-term view that are successful in nurturing the brands and in taking the time,” he opined.

“When Bernard Arnault bought Moynat, he acquired it for his grandchildren. With a heritage brand, established 50 or 100 or 200 years ago, you have a different approach to timing, to momentum, to longevity.” At LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, most of its portfolio is made up of heritage brands, and a few of their misfires were not, such as Fenty, he said.

Also, mistakes are easier to cushion with a heritage brand, he contended. “Perhaps the designer is not the right fit, but the brand will survive and you have a story to tell. A heritage brand can survive the death of the founding designer. If you invest in a celebrity brand, or one that relies on new trends, or in new technology, you have a momentum to catch, meaning that probably you will invest more into marketing and brand awareness.

“When you have a strong brand with a strong heritage that is exhibited in museums, it has credibility and it’s part of the culture. Look at the number of exhibitions on Dior, Chanel, Balenciaga. People buying pieces of Chanel or Dior, they feel they are also buying a piece of culture.” Also, designers are often more inspired by the archives, “they know where to start and make it their own, reinventing the legacy, adapting the style,” rather than working with a white page, de Lummen said.

Fashion is more erratic than shoes or leather goods, jewelry or perfumery. “Big leaders like Chanel and Gucci can go through the bad times because they also have a large business in other categories. If you are a newcomer, and you hit a low moment, you are more fragile. If you have a hot collection selling very well, it might be for one season, maybe two. And when you have a lot of money coming in suddenly, usually you make your business plan based on that success.” Generally, “it’s those booming brands that interest private equity funds,” but that moment may be fleeting.

Best of WWD

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance