Supermarket wage wars risk derailing interest rates cuts

Shop floor workers at Asda and Marks & Spencer got good news last week after both retailers announced inflation-busting wage increases for frontline staff.

Asda on Friday announced it would put £150m into higher pay, increase hourly wages by 8.4pc £13.21 in London and £12.04 outside the M25.

Days earlier Marks and Spencer had said it would boost hourly pay for its 40,000 from £10.90 to £12 in April – a 10pc rise. London staff will get an hourly increase of more than £1 to £13.15.

What will be cheered in the aisles will be less well received in Threadneedle Street.

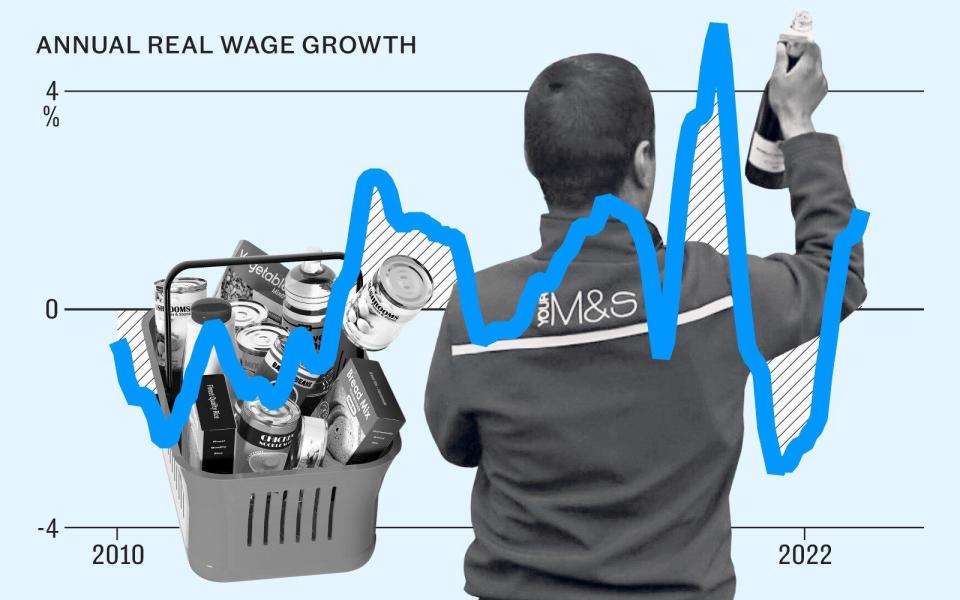

Bank of England officials are monitoring wage rises across the economy with concern. Officials have repeatedly said that continued strong pay growth is giving them pause when it comes to lowering interest rates.

“This is a key risk and a key threat to the argument that interest rates are going to be reduced in the second half of this year, or maybe even this summer,” says Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics.

Wages in the private sector rose by 6.2pc in the final three months of the year when excluding bonuses, figures from the Office for National Statistics show.

While supermarkets employ only one million of Britain’s more than 30 million workers, the sector has seen some of the fastest wage growth in recent years.

Pay in wholesaling, retailing and hospitality rose by 7.2pc in the final quarter of 2023, a whole percentage point faster than the national average.

Clive Black, of Shore Capital, says: “Most of the major players are coming out for store staff at around £12/hour, which means further inflationary pressure in the food system.

“It is not just supermarkets that face this pressure but farms, food factories and distribution centres.”

Asda and Marks & Spencer are among the last grocers to raise their pay to around £12 an hour. Executives within the industry are not clear that it will signal the end of strong pay rises within the sector.

Bumper settlements have now been going on for years: Sainsbury’s has boosted pay by 50pc in the last five years alone – more than twice the rate of inflation when including housing costs over the same time.

The implications go beyond the supermarket sector. Gary King, managing director of recruitment firm Evolve Hospitality, says: “Catering companies, restaurants, hotels have had to increase their salaries to keep in line with retail and delivery and so on.

“During the pandemic there was very little hospitality so people moved out of the sector and into other sectors. To attract them back has been tough, so wages have gone up.”

This struggle is easily visible in the “staff wanted” posters in seemingly every restaurant and pub.

While King says the pace of salary increases have slowed somewhat, the pressure to compete for workers means it is still at a fairly high rate.

Industries are still adjusting after Brexit and are having to pay more to recruit for some roles in the UK.

Julie Mordue, at recruiter Greenbean, who helps call centres find staff, says finding enough workers is a “struggle”.

“We are in competition with retail, hospitality, leisure, all of the industries that have got transferable customer service and soft skills such as empathy and listening. So we’re all fighting for the same talent.”

The ratcheting effect of minimum wage may trigger a fresh round of pay increases.

From April, the minimum wage will rise by nearly a pound to £11.44 an hour for anyone aged over 21. A similar rise the year before means the minimum wage will have risen by just over 20pc in only two years.

Neil Carberry, head of the Recruitment and Employment Confederation, says: “For supermarkets who traditionally have not paid the national minimum wage, they paid 50p, £1, £1.50 above that, they’re feeling pressure to move things up.”

Companies must adjust the pay of all workers when minimum wage increases.

Carberry says: “If you’re a small hospitality firm and you pay your bar manager £1 or £1.50 more per hour than your bar staff, then clearly if your bar staff get a 10pc rise there is pressure to deliver a similar increase and the differential above it.”

Upward pressure on pay is stretching many businesses. This, he says, is “a real challenge”.

As a result, many companies with lower-paid staff are having to find ways to recoup profits elsewhere, either by increasing prices – another inflation driver – or reducing opening hours. In areas like logistics, Carberry says companies have started investing far more in automation to cope but for many service providers this is not an option.

All this means pressure to increase pay is impacting not just wage growth but also inflation across the services sector more broadly, two key metrics Bank of England rate-setters are concerned about.

This spells trouble for the Bank of England, where policymakers are adamant they need to see salaries normalising before they can start to bring down interest rates from their 16-year-high of 5.25pc.

Traders are betting that the Bank will deliver the first cut to borrowing costs in June, but Dales warns this may prove optimistic.

“If you look at the pay settlement data for the pay rises that businesses are actually giving their existing employees, most of those are in the 5-6pc bracket, which is still too high to be consistent with the 2pc inflation target,” Dales says. “They’re expecting to continue to do that for next year as well.”

His concern is shared by Jack Kennedy, senior economist at hiring platform Indeed, who labels expectations of a June rate cut “a little ambitious”.

“Those kinds of lower paid in-person sectors are still seeing pretty strong wage growth, in many cases, still sort of running between 7pc and 10pc,” Kennedy says. “Jobseeker interest has remained quite substantially down on what it was pre-pandemic.”

One of the Bank of England’s most senior officials last week said more evidence was needed before the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) could think about lowering borrowing costs.

Dave Ramsden, who sits on the MPC, said there were still signs of inflation proving persistent.

The Bank’s chief economist, Huw Pill, also expressed caution about imminent rate cuts when he warned on Friday that policymakers risked “being lulled into a false sense of security”.

It means joy about rising wages may prove short-lived. Those enjoying a pay bump may soon find themselves paying the price as borrowing rates remain high.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance