Thousands of vulnerable people missed out on support at start of pandemic

As many as 800,000 clinically extremely vulnerable people may have missed out on government support at the start of the Covid pandemic, with some elderly and blind people struggling to access food, parliament’s spending watchdog has found.

The Public Accounts Committee said “poor data” meant that it took too long to identify more than a third of the 2.2 million people who should have been shielding at a time of urgent need.

Of those who slipped through the net, almost half – 375,000 – could not be contacted due to missing or incorrect telephone numbers in their NHS records.

In a report released today, MPs also found that the selective application of “at risk” criteria meant some elderly and vision-impaired people were not advised to shield, leaving them struggling to get enough to eat.

Meg Hillier, the committee’s chair, said that while the plans were eventually “sensibly” devolved to local authorities, it raised questions about the balance between central decision-making and local knowledge.

“The shielding response in the Covid pandemic has particularly exposed the high human cost of the lack of planning for shielding in pandemic-planning scenarios. It also highlights the perennial issue of poor data and joined-up policy systems,” she said.

“People were instructed to isolate, to protect themselves and others – but the cost of this protection was reduced access to living essentials like food, and an untold toll on the mental health and wellbeing of the already most vulnerable.”

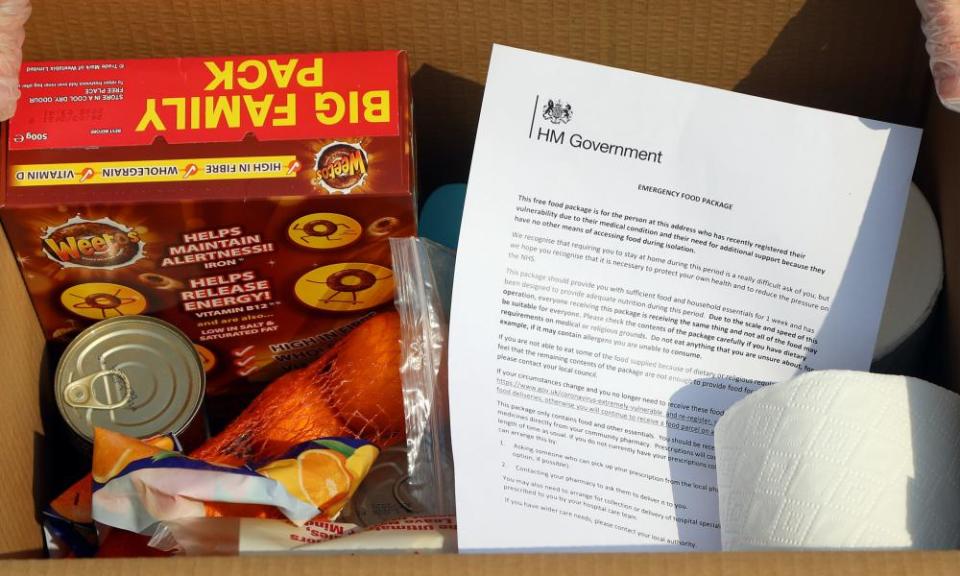

In March last year, the government asked those in England considered the most vulnerable to “shield” and drew up a £308m programme to support them with food, medicines and basic care.

Those defined as “clinically extremely vulnerable” included people in treatment for cancer, transplant recipients, those suffering from severe respiratory and kidney conditions, and people with Down’s syndrome.

Initially, NHS Digital drew up a list of 1.3 million people who would be eligible for support while they were required to isolate at home but that rose to 2.2m over the next six weeks.

Related: A year inside: what shielding has meant for the most vulnerable - podcast

The committee said the process became a “postcode lottery” after local GPs and hospital doctors were invited to review the list and use clinical judgment to add or remove people.

The resulting increase in the numbers ranged from between 15% and 352% depending on the local authority area, with the list more than doubling in 33 authorities. The committee said that this represented an “unacceptable level of variation”.

An £18.4m central contact centre set up to trace people who did not respond to an initial letter advising them to shield failed to reach 800,000 people. Officials from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) told the committee they had tried to engage with those affected – by post, email and phone.

After failing to make contact with clinically extremely vulnerable people, it took the government a month for the central contact centre to pass details to local authorities, according to the report.

The committee said the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government still did not know whether these people had been contacted by their local authorities.

“The programme suffered from the problems of poor data and a lack of joined-up systems that we see all too often in government programmes,” it said. “As a result, government took too long to identify some clinically vulnerable people at a time when their need was urgent.”

Some groups who were not initially advised to shield were made more vulnerable as a result, the committee found.

“Charities have told us how the over-70s and the blind and partially sighted, who were not advised to shield, and therefore not eligible for support through the programme, struggled to access food,” MPs said. They added that the Royal National Institute of Blind People had said that the “government’s ‘one size fits all’ approach left many blind and partially sighted people behind”.

DHSC has since developed a new risk assessment tool, QCovid, to identify vulnerable people based on wider factors that make them at more risk from Covid. “These risk factors include ethnicity, BMI, postcode and age. DHSC used this tool to identify an additional 1.7m clinically extremely vulnerable people in February 2021,” the report said.

The government called the report’s findings “disappointing and misjudged” saying the initial shielding guidance had been agreed by the four UK chief medical officers on the basis of the latest available evidence. “Since then we have learned more about the virus and adapted our approach, which has enabled us to protect those most vulnerable by providing them with shielding guidance and prioritising them for vaccination,” a government spokesperson said.

“During this globally unprecedented emergency, we worked across multiple government departments to build and deliver an urgent national scheme in record time, identifying 1.8 million clinically extremely vulnerable people and providing them with vital food and medicine to help them shield effectively.

“We made significant efforts to contact people by letter, text and telephone and worked closely with councils to ensure we reached them. Many people chose not to take up the offer of government support as they felt they didn’t need it.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance