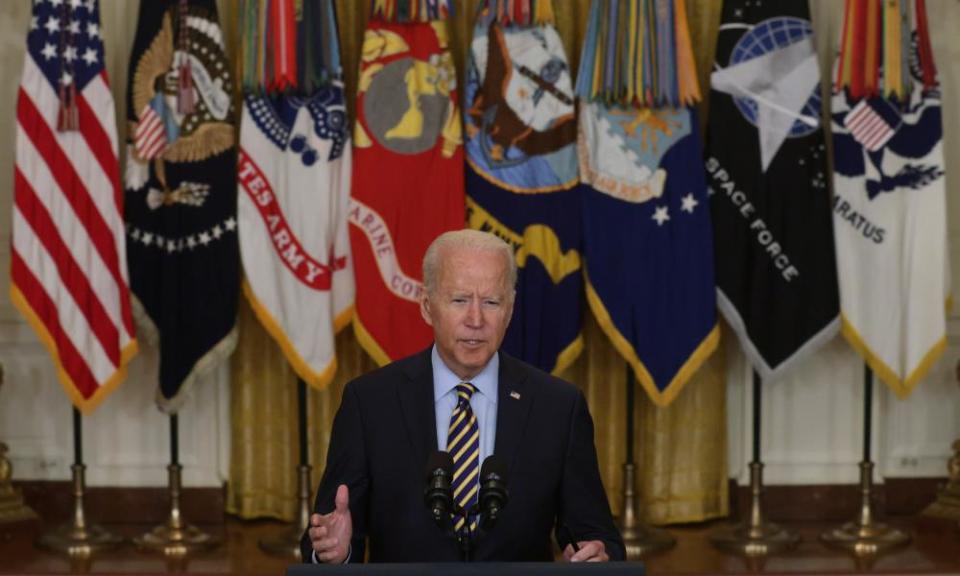

As US troops leave Afghanistan, what will future policy look like?

As the US nears completion of its military withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Pentagon is supposed to switch to “over-the-horizon” counter-terrorist operations in the country. But it is far from clear yet what those will look like in practice.

The Biden administration has made it clear that after the end of August it will not provide air support for Afghan forces intended to bolster the Kabul government, though it is possible that will be reappraised if provincial capitals fall to the Taliban. However, Gen Kenneth McKenzie, head of the US Army Central Command, said on Sunday that the US would continue airstrikes in support of Afghan forces “in the coming weeks, if the Taliban continue their attacks”.

The stated objective of future operations is to pursue the original war aims of 2001: to stop Afghanistan being a training ground and launching pad for attacks on the US by al-Qaida. After 20 years of fighting, al-Qaida still has a presence in the country, alongside another threat, Islamic State.

The US says it will continue to target those groups if and when they strengthen their foothold in the growing share of territory under Taliban control, but it will do so from bases outside the country.

Among the questions that have not been answered, at least not publicly, is the extent of future US involvement. Will it seek to have a constant “unblinking eye” in the skies above Afghanistan, or make periodic forays? What level of al-Qaida or Isis presence would trigger an attack? Would the Taliban be targeted on suspicion of cooperating with terrorist groups? And what bases would the US be able to use? How far away is the horizon going to be?

All these issues were debated more than a decade ago when Barack Obama was considering withdrawal from Afghanistan, as advocated by then Vice-President Biden. But Obama was ultimately persuaded to conduct a troop surge instead and so no conclusions were reached.

“There was a lot of effort put into casting about for what the over-the-horizon options might look like. The fact that they were all suboptimal was one of the factors that contributed to perpetuating the American military presence in Afghanistan,” said Laurel Miller, a former acting special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan, now Asia programme director at the International Crisis Group.

Related: Taliban claim to hold 85% of Afghanistan after taking key border crossing

The horizon US aircraft will be flying over could be very distant indeed. The Biden administration has been holding talks with central Asian states in recent days in which the subject of possible bases is very likely to be on the top of the agenda. A delegation is heading to Uzbekistan this week, but there is no sign of progress so far.

“I’m sceptical that the central Asian options are going to work out,” Miller said. “At a minimum, I don’t see how you pull that together very quickly.”

David Petraeus, who served as head of US Central Command, commander of US and allied forces in Afghanistan and director of the CIA, said there would be no straightforward way of continuing military operations after withdrawal.

“‘Over the horizon’ in Afghanistan will be enormously challenging, vastly more so than most other countries,” Petraeus told the Guardian. “Obviously it is landlocked and a considerable distance from our closest bases in the Gulf states.

Related: Inside Afghanistan’s looted Bagram airbase after US departure – in pictures

“It seems pretty clear that we’re not going to keep anything in-country, and we will probably not have a base in a neighbouring country, so unless an aircraft carrier is parked off southern Pakistan, any drones, close air support and other aircraft will have to fly a substantial distance going to and from Afghanistan, with very limited time on-station for drones that are not air-refuellable, and with many aerial tankers required to keep on-station aircraft that can be refuelled in flight.”

Maintaining an aircraft carrier in the Arabian Sea as a base for Afghan operations would be prohibitively expensive as it would have to be constantly supplied and its crew rotated, using far more resources and troops than the 3,5000-strong military presence that has just been withdrawn from Afghanistan.

US commanders may also be restricted by host governments in the Gulf on the use of bases to launch Afghan air operations.

“All of this is just enormously challenging and difficult. And the truth is, it didn’t have to happen. We could have easily maintained a sustainable, in terms of blood and treasure, commitment, which I think the history of the last 20 years tells us is necessary,” Petraeus said.

“If you actually take your eye off al-Qaida and the Islamic State, if you don’t keep pressure on them, if you stop disrupting them, then at a certain point you’re going to end up having to re-engage, and it is always more difficult when you have, as in Iraq, given up your bases and infrastructure and reduced your intelligence presence.”

Jason Dempsey, a former infantry officer who served in Afghanistan, argued that the logistical difficulties were not that different from those in other parts of the world where the US flies counter-terrorist operations, and the obstacles could have the benefit of focusing minds on non-military means to meet US objectives in Afghanistan.

“America has to get beyond the idea that the only way it can influence other nations is with the military,” Dempsey, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, said.

“We have to find out how to use the levers that we do have to keep things in check,” he added. “The Taliban doesn’t want to be a pariah state, so that’s one of the levers we have. So long as we’re willing to commit to supporting Afghanistan, I think we can continue to have leverage.”

However, Dempsey said there appears to have been surprisingly little urgency in putting non-military measures in place.

“One of the head-scratchers is the fact that we still don’t have an ambassador in Afghanistan,” he said. “So if that indicates our level of seriousness, that’s pretty embarrassing.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance