Whisper it, but private equity returns might just be too good to be true

A new paper has suggested private equity houses have been adjusting fund performance figures to smooth returns and increase their appeal to investors.

A research paper written by Maria Borysoff and Gregory Brown has claimed private equity funds regularly shift reported losses and profits in funds to smooth overall returns.

The traditional metric used by private equity houses to measure returns is multiples of invested capital (MOICs), and the paper analysed over 1,000 buyout funds and their MOICs over time.

It found that there was an unusually low frequency of multiples just below one in MOICs, which would suggest a loss, compared to an unusually high frequency of payouts equal to or just above one.

“This behaviour is consistent with funds attempting to minimise loss ratios which are commonly used to assess the riskiness of funds by outside investors and consultants,” explained the paper.

More experienced private equity partners appear more likely to use this ‘loss avoidance’ technique, especially while fundraising for their next fund. If the technique is used, the partners “raise significantly larger subsequent funds relative to their peers,” the paper said.

However, while this may benefit the private equity partners, loss avoidance “is negatively associated with the final fund returns that investors receive,” it warned.

Last week, the Financial Times reported that data compiled by Preqin revealed that private capital firms had taken more money from investors than they had distributed back to them in gains for six years in a row.

Over the last 14 years, private capital funds have bought in $821bn more than they have distributed, or $1.6 trillion over the last six years, as money brought in has remained locked in funds that aren’t distributing any returns.

Despite this, the seven largest listed North American private capital companies have earned over $100bn in labour and stock-based compensation costs over the last five years.

Private equity bosses have consistently argued they’re better at running businesses, which would explain why the paper found a lower-than-expected level of losses in portfolios.

However, that doesn’t explain why funds have sucked in so much capital over the past 14 years with minimal distributions to investors.

The one-way flow of capital suggests funds have struggled to realise portfolio company uplifts.

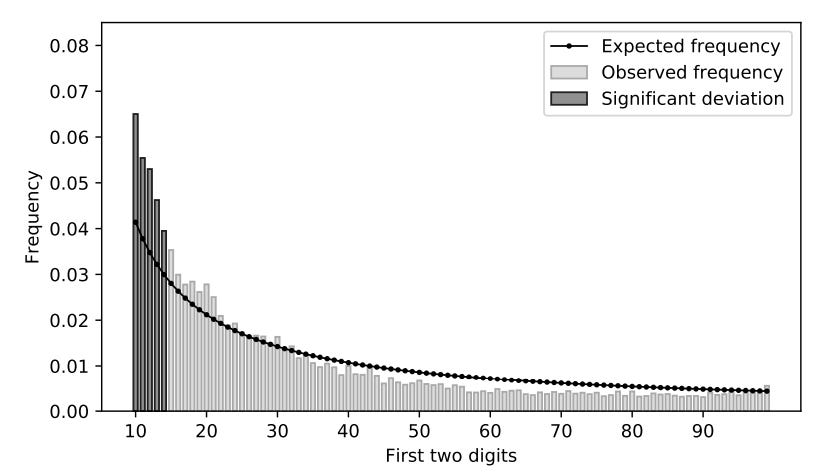

Another analysis the paper did involved Benford’s Law, which states that numbers starting with the digit ‘1’ should appear more frequently than numbers starting with ‘2’, which are then more frequent than ‘3’ and so on.

This distribution is often used when analysing data that may have been prone to tampering, such as election fraud, as those editing the underlying figures will not take into account the expected statistical distribution.

When the first two digits of reported MOICs are analysed across all private equity funds, the values do not match Benford’s Law, clearly signally data manipulation.

This effect is especially large when a fund is raising money, but once a fund is closed for investment, the effect vanishes.

“While our analysis provides no evidence of improper or fraudulent behaviour by funds, it does suggest that funds may potentially reallocate resources to get small losers to the break-even point,” the paper concluded.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance