Why the remote Wakhan Corridor is your travel bucket list destination for 2024

This sliver of land between Tajikistan and Pakistan is unlike anywhere else on earth. Sophie Ibbotson sets out to explore beyond ‘The Roof of the World’, which should be on your travel bucket list for 2024

Drive across the Roof of the World and you have to end up somewhere. That “somewhere” is the point at which the high altitude desert of the Pamir falls away into a valley before rising again, this time shrouded in snow, in the mountains of the Hindu Kush.

On a map, the valley is the narrowest finger of territory, a sliver created by imperial cartographers to keep the British and Russian Empires from touching. Its name appears time and again in the accounts of Great Game explorers, geographers, and spies: it is the Wakhan Corridor.

In the 21st century, the Wakhan is all but forgotten by the outside world. Its southern side is one of the remotest parts of Afghanistan; and on the northern side of the river demarcating the border is Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO), the most sparsely populated part of Tajikistan. There is a road of sorts, but each spring more and more sections of it are reclaimed by rockfalls and streams, and once the villages peter out, wild camels are more numerous than cars. Every now and then someone says that the Chinese will build a highway through the Wakhan as part of their One Belt, One Road programme, but for now it still feels like the end of the world.

Getting to the Wakhan is the first part of the adventure. Turkish Airlines has two reasonable connections from London to Dushanbe (Tajikistan’s capital) via Istanbul each week, but since Tajik Air went bankrupt, there are no scheduled domestic flights within the country. I lucked out and hitched a ride on the Aga Khan’s helicopter to Khorog, the largest town in GBAO, but otherwise it is a two day drive to get here, and then another half day to Ishkashim, the gateway to the Wakhan.

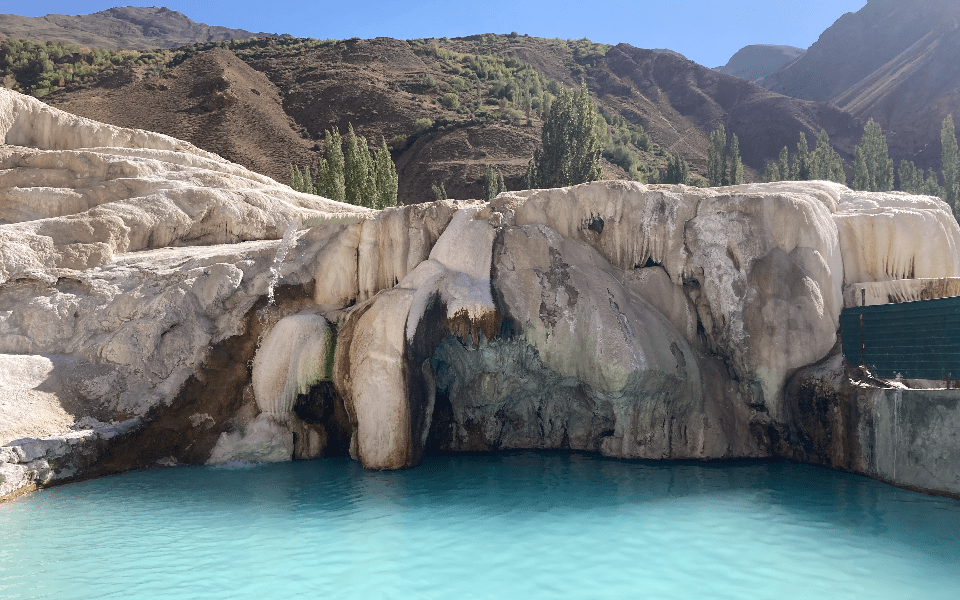

The landscape is dry and harsh, the road clinging to a brittle cliff high above the River Panj, the Oxus of antiquity. Stops along the way — Castle Karon, Vamar Fortress, the sulphur baths at Garm Chashma — are welcome breaks from driving, but also reminders that in spite of its accessibility, this territory has not only been inhabited but also been strategically important for thousands of years.

I’d visited Ishkashim half a dozen times before, but never stayed the night on the Tajik side. The town is split in two — one part in Tajikistan, the other in Afghanistan — and on each previous occasion I’d been in a hurry to cross the river. Now I had time to wander, to chat, and to see clearly the historic and cultural ties linking a single community divided between two nation states.

Tajik and Dari are, to all intents and purposes, the same language. The Pamiri people share strong familial ties regardless of what it says on their passports, and are predominantly Ismailis (followers of the Aga Khan), which sets them apart from orthodox Muslim groups. When the cross border markets in Khorog and Ishkashim reopened after prolonged closures due to security concerns, it was a cause for celebration. Not only do they boost trade, but trans-border relationships, personal and professional, can be maintained.

The Wakhan’s treasures lie to the east of Ishkashim, so after a night of feasting on plov — Tajikistan’s national dish, the local variant of pilau or biryani — watermelon, cherries, apricots, and other fruits from the town’s prolific orchards, I got back in the 4×4. For me, the draw of this area has always been the awe inspiring scale and ruggedness of the landscapes, but this time I wanted to better appreciate how and where ancient travellers made their marks. You don’t have to drive too far.

Shoira has her guesthouse at Namagut; there’s only a handful of houses in the village, so it is easy enough to find. She grows vegetables, raises goats and cows, and until recently had a puppy, but one night it was snatched by wolves. The shady orchard makes an idyllic campsite, but the best bit is the view: across the river you see Afghanistan, and right next door — less than two minutes’ walk away — is the Kah Kaha Fortress.

It is said that there were once seven fortresses in the valley, a fairly impregnable line of defence along the Wakhan. They protected the Silk Road caravans passing through from China and the Indian Subcontinent on their way to Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran. The location of Kah Kaha was so well chosen, and its height so substantial, that the Tajik Army still has a sentry post on top. The guards are friendly enough, however, and probably grateful for the company. Visitors are few and far between.

Yamchun Fortress, further on, is larger still, though only a fraction of it has thus far been excavated. Local legend has it that it was built to resist the Arab invasion led by Ali (son in law of the Prophet Muhammad), but there’s no historical evidence that Ali ever came to the Wakhan, and the oldest parts of the fort probably date as far back as the 3rd century BC.

The upper walls and tower of Yamchun are fairly intact, and when you scramble down into a gully and then up the ramparts to the top, you’ll undoubtedly be breathless but have commanding views in both directions along the Wakhan. Yamchun is already on UNESCO’s tentative list for recognition as a World Heritage Site, and The World Bank has identified it as one of the most culturally important structures in Tajikistan. The Bank has committed funding to preserve and develop the site, in partnership with international universities. It is hoped that the archeological team will come for the 2020 season, enabling us to better understand its significance.

Fortresses demonstrate wealth and power; but ordinary people have contributed just as much to the Wakhan’s heritage. At Langar, high above the confluence of the Panj and Wakhan Rivers, is the largest petroglyph site in the Pamir. Since the Stone Age, artists have created some 6,000 artworks here, depicting everything from ibex and men on horseback, to stickmen and religious symbols. There were sun and fire worshippers in the Wakhan long before the arrival of Islam, and this is attested by some of the rock art.

Pre-Islamic beliefs are often interwoven with Ismailism in the Wakhan.

At Namagut and elsewhere, I saw the horns of ibex and Marco Polo sheep above doorways; they offer protection to the household. Bibi Fatima Spring is named after the daughter of the Prophet, but it is linked to much older, pagan practices. Bathing in the warm waters is believed to boost fertility, and local women still come here to pray for a child.

A day on the road in the Wakhan isn’t easy; it’s uncomfortable, and at times it would be faster to walk. But there are few places in the world which are accessible by 4×4 yet still feel so wild, where you’re so cut off from the modern world that 500, or even 1,500, year old traditions can still be part of everyday life. A true bucket list destination for 2024.

Visit the Wakhan Corridor yourself

Paramount Journey (paramountjourney.com) offers a nine day 4×4 tour of the Wakhan Corridor, starting and finishing in Dushanbe, from £1,374 per person.

Read more: Dine in underground tunnels in this French city easily reachable by Eurostar

Read more: The Divine Madman of Bhutan and his legacy of many penises

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance