Calls for 'shock and awe' spending to avert global recession

Pressure is growing on governments and central banks to spend hundreds of billions of dollars to stop the global economy spiralling into recession.

Gita Gopinath, chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), on Monday urged policymakers to put in place “substantial targeted fiscal, monetary, and financial market measures” to counter the negative economic effects of coronavirus.

“The goal is to prevent a temporary crisis from permanently harming people and firms through job losses and bankruptcies,” she wrote in a blog.

Separately, Deutsche Bank strategist George Saravelos said governments and central banks should organise “a coordinated fiscal response on the order of magnitude of the Lehman crisis, above 1% of global GDP.” That would equate to somewhere around $850bn (£647.5bn).

‘Pricing a global recession’

The calls for what JP Morgan dubbed “shock and awe” spending came as stock markets and oil prices went into free fall, extending a global panic among investors that has roiled markets.

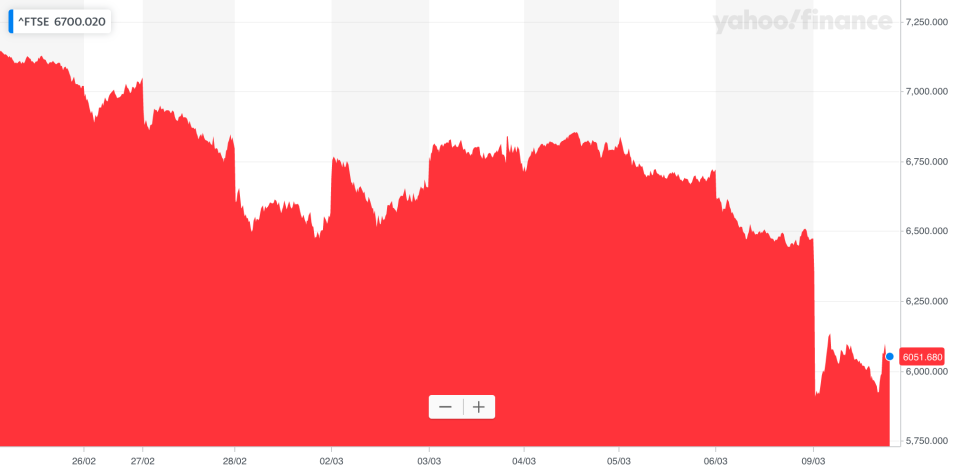

The FTSE 100 (^FTSE) suffered its fourth biggest fall on record on Monday and trading in the US was temporarily halted after steep losses triggers ‘circuit breakers’ in stock markets.

The immediate spur was the beginning of an oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, which sent shockwaves rippling through global markets. The surprise dispute risks sparking a wave of bankruptcies in the US shale industry.

However, global markets had already been under pressure amid fears about the economic fallout from coronavirus. The FTSE 100 index is down more than 20% since mid-February and other major indexes around the world have seen falls of similar magnitude.

“The market is in the process of pricing a global recession,” Deutsche Bank’s Saravelos wrote in a note on Monday.

‘Unique responses’

Analysts and investors are now looking to governments and central banks to take action, calling for the type of coordinated response not seen since the 2008 financial crisis.

“This virus requires a unique set of policy responses across the public health, monetary and fiscal spheres,” JP Morgan analysts wrote in a note on Monday.

Fears about the economic fallout from coronavirus first emerged in late February. Factories and shops were shut across China to limit the spread of COVID-19, prompting downgraded growth forecasts for the country’s economy.

Investors and economists began to worry about similar slowdowns outside of China as the virus spread to places like Italy, South Korea, and the United States. Airlines and other tourism-linked industries also began to report slumping demand as consumers put off travel. UK regional airline Flybe last week went bust and blamed a coronavirus-linked slowdown.

JP Morgan analysts said Monday they were starting to see “signs of emerging credit and funding stress” sparked by the coronavirus outbreak. If banks pull back from lending, that could create problems for businesses so far untouched by the coronavirus driven slowdown.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) warned last week the economic impact of coronavirus is the biggest threat to global growth since the 2008 financial crisis.

Policymakers have already begun to react. The US Federal Reserve unexpectedly cut interest rates by 50 basis points last week, Australia announced a billion dollar stimulus package over the weekend, and Germany has signed off on €12.4bn (£10.7bn, $14.1bn) of spending to boost the economy.

Last week, the IMF also announced it would make $50bn available to fight COVID-19 and the World Bank pledged $12bn in emergency funding.

The actions have so far done little to reassure the market. The S&P 500 closed 3% lower on the day of the Fed rate cut and the German DAX (^GDAXI) was down 8% on Monday. Deutsche Bank’s Saravelos said policy announcements so far had been “underwhelming.”

G7 finance ministers and central bankers said last week they “stand ready to cooperate further on timely and effective measures” but did not provided any detail.

UK budget, ECB in focus

More action is expected this week. UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak will deliver his first budget on Wednesday, with a coronavirus response likely.

“We expect COVID-19 to influence the budget announcement next week and currently see fiscal policy being the weapon of choice in the fight against the virus,” Barclays’s economist Christian Keller wrote in a note.

Then, on Thursday, the European Central Bank (ECB) will publish its latest monetary policy decision. The central bank’s headline deposit rate stands at -0.5% and the main refinancing rate is 0%, leaving little space to meaningfully cut interest rates.

Instead, analysts expect a more targeted response, including an extension to its bond buying programme in a bid to keep credit flowing to businesses.

“The only effective measures the ECB could take would be credit-enhancing measures, like more purchases of corporate bonds, (temporary) changes to the collateral rules, targeted liquidity injections to support extensions of bank loans to companies with financial problems due to COVID-19, or a general liquidity injection,” wrote Carsten Brzeski, chief eurozone economist and global head of macro at ING.

Next Monday Andrew Bailey will also succeed Mark Carney as governor of the Bank of England. Bailey said last week special measures to support UK small businesses may be needed and details of proposals could come shortly after his appointment.

Speculation is also growing about a possible rate cut on 26 March, when the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee makes its next announcement.

‘Out of ammunition’

However, unlike the global financial crisis, experts say central banks have limited ability to tackle the current crisis. Most have limited room to lower interest rates and even then it is not clear that cutting rates would have much effect.

“The ECB’s dilemma is not only that it has basically run out of ammunition but also the fact that there is very little the ECB can actually do to cushion the economic impact from the unprecedented mix of supply-side and demand-side shock,” ING’s Brzeski wrote. “Even cheaper money alone will not do the trick.”

ING called for government spending programmes including “state guarantees, bridging loans, (temporary) tax relief, subsidised short-work schemes or even tax forbearance.”

“Central banks are bit players in the current crisis,” Bank of America analysts said on Monday. “The virus is a supply shock: health policy and targeted fiscal policy are much more important than monetary policy.”

Deutsche Bank’s Saravelos said the ECB should this week “tell governments it is time to step up.”

Italy’s prime minister Giuseppe Conte on Monday promised “massive shock therapy” in an interview with newspaper La Repubblica and the country’s economic ministry separately said they were planning a “vigorous” response. Around 16 million people in Italy’s industrial north are currently under lockdown.

While targeted government support could help businesses survive the shocks from the oil price war and coronavirus, stock markets could take longer to settle down.

“The catalysts for a market turn are more likely to be some combination of peak infection rates, underweight positioning and very cheap markets,” JP Morgan analysts wrote.

Watch the latest videos from Yahoo UK

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance