From Tide Pods to Coach bags, how Fortune 500 companies use museums of their hits and misses to drive success

It took five decades of failure to turn Tide Pods into an overnight success.

The “unit-dose” detergent pods became one of the biggest-ever hits for consumer products giant Procter & Gamble not long after their 2012 debut. But P&G had launched an earlier attempt in the 1960s, called Redi-Paks, to utter indifference from consumers. Other iterations in the following decades, such as Rapid Tabs in the 1990s, also fizzled; the company just couldn’t quite master the formula for optimal release of the detergent. That is, until it did; now Tide Pods are a top seller in a $3 billion market.

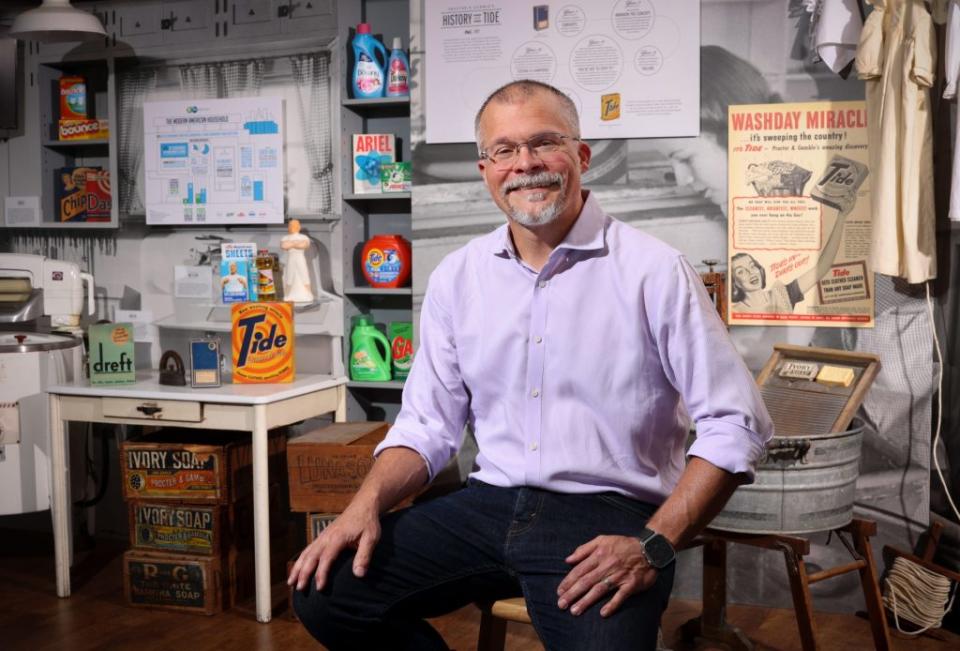

Today, the Tide Pods’ failed forebears have a place of honor in the “Wall of Failures” exhibit at P&G’s Heritage Center and Archives in Cincinnati—an internal museum at headquarters aimed at helping P&G’s product-development teams find the next big thing. The Heritage Center isn’t open to the public, but guests are welcome to visit, and staff are urged to do so. Over the years, the company has kept meticulous records of its misfires, seeing them as a valuable resource. “Failure cases are a critical learning area,” says Shane Meeker, P&G’s historian and corporate storyteller. “If you’re not failing, you’re not innovating.”

P&G is hardly alone among big corporations in running an in-house museum. Countless others meticulously maintain storehouses of records, prototypes, board meeting minutes, discontinued gadgets, old press releases, marketing materials, and all manner of paraphernalia. In Billund, Denmark, Lego has five miles’ worth of shelves in climate-controlled facilities where it stores nearly every “brick set” it has ever produced. At the Atlanta airport, Delta Air Lines has two entire hangars that showcase ephemera ranging from old propeller-driven planes to bar carts from aviation’s glamorous age.

Many companies go a step further, employing trained historians and organizing their archives into exhibits that tell stories and impart important lessons. These collections open stunning windows into the business world’s history. But for the companies, they transcend nostalgia and marketing: They serve a practical purpose, guiding product development, C-suite decision-making, and culture-building. Some are open to the public, but for most that’s not the main point: For the archivists, their coworkers are the ideal visitors.

“We’re more than just a location to look at the past,” says Alan Dranow, senior director of program management at Walmart. The mega-retailer operates a museum housed in an old five-and-dime-store in the center of Bentonville, Ark., with exhibits such as recreations of founder Sam Walton’s office and of his pickup truck, which attract many visitors. The Walmart museum is undergoing a major renovation and is set to reopen this fall.

The unifying principle among these disparate collections is that in an economy full of young disrupter companies, older brands have a huge intangible asset in their rich and long histories—resources that can help them build and fine-tune products for the future.

Tapestry’s Coach subsidiary, founded in 1941, keeps a model of almost every handbag it has ever made, held in secure shelves at its New York headquarters. (Coach also displays nearly 200 vintage bags to the public in a huge vitrine at the entrance to its Manhattan offices.) The idea is to inspire new creations from executive creative director Stuart Vevers and his teams.

Coach’s designers have emulated the brand’s iconic Bucket bag, for example, in their current hot-selling version—finding new success by playfully echoing a design that customers found appealing more than 50 years ago. “Traditional European luxury companies do this,” says Coach’s archivist Ryan Bollwerk, who recently gave Fortune a tour. “But we are the only ones who have this at scale in North America.” Coach’s holdings include the first handbags created by pioneering designer Bonnie Cashin; staff and visitors can trace how the “turnlock” and “kisslock” clasps Cashin favored in the 1960s became Coach signatures over the next several decades.

Outside of the world of fashion, Reckitt—the maker of Lysol but also of healthcare focused products such as Dettol antiseptic—has archives to help guide new product development. Reckitt, which was primarily focused on health products when it started near London in the 1840’s, plays up its history so that employees feel they are making products that help the greater good. And the developers often find they can still borrow from Reckitt’s old ideas.

“I have R&D people who’ll come in and look at old formulations and see what’s changed with the product and inspire them,” says Dr Grace Chapman, Reckitt’s heritage advisor and the holder of a Ph.D. in medical history.

At Lego, the archives and museum detail the toy brand’s evolution since its founding in 1932, when the first toys were wooden horses. The famous plastic bricks with studs that we know today were introduced in the late 1950’s. Visitors learn, for instance, that Lego is a mash up of the Danish words “Leg” and “Godt” which mean “play well.”

There are also nerd-friendly exhibits of product lines like the Star Wars sets in the late 1990s. Those sets represented a big turning point in Lego’s history, launching it into a new Golden Age fueled by franchise-themed sets. Lego has spent years recreating its collection by amassing two sets of each toy it has made since 1958—one set for workers and visitors to Lego’s home office, and the other stored in a secure, Fort Knox-style facility near Billund.

Museums and archives also help companies, particularly those of a certain age, foster a feeling of belonging to an entity with a history and a greater purpose, without the “here today, gone tomorrow” vibe that characterizes tech unicorns. That sense of purpose is especially important among new hires.

“If you’re not careful and not making sure that those employees are introduced to the history and values, you will end up being just like any other company,” says Lego historian Signe Wiese, who gave Fortune a tour of Lego’s massive archives.

Over at Walmart, CEO Doug McMillon as long been a big advocate of the museum, recognizing its role in rallying the troops around modernization efforts while not losing sight of what Walmart a massive success to start with. “Doug is Mr. Culture,” says Dranow.

Of course, a little bit of nostalgia doesn’t hurt to achieve such goals, especially for a company like Delta that can tap people’s fascination with the most glamorous times in commercial aviation. The Delta Flight Museum displays kitschy items such as Champagne bottles in the shape of a king (Delta’s Sky Club lounges used to be called “Crown Rooms”). But among the most in-demand materials are its collection of all its flight attendant uniforms through the years (including the groovy, highly colorful ones from the 1960s, when most flight attendants were “stewardesses”). Delta trots out the uniforms at corporate events, but they’re also key in the onboarding of new employees. Delta’s director of archives, Marie Force, says the displays often evoke intense emotional reactions: “There’s something about seeing these uniforms being worn, and keeping them alive,” she says.

At some companies, C-suite leaders are avid users of these resources. At Coca-Cola, the archives and open-to-the-public museum hold artifacts like handwritten order forms for the ingredients of its top-secret formula, or the original drawings for its iconic bottle shape. But the beverage maker’s top leaders have also tapped the archives for guidance in crises. When COVID struck four years ago, Coca-Cola brass asked the archives team to unearth records detailing how leadership had handled the 1918 influenza pandemic—seeking clues for handling the new health emergency. In such a situation, storied companies may have an edge over younger ones. “You have to survive long enough to have an archive that has enough information to look back on,” says Coca-Cola’s archives director, Sarah Rice.

Some of the most useful archives include information on a company’s difficult times along with its triumphs. Visitors respond well to the transparency: Coca-Cola’s archives about the New Coke flop of the 1980s are popular, for example, and so is P&G’s Wall of Failures.

Above all, well-stocked archives can help companies avoid the trap of short-termism. “It suggests a value orientation in the company toward thinking bigger,” says Caitlin Rosenthal, a history professor at the University of California at Berkeley. There’s nothing like a museum to remind leaders that their choices, and their consequences, could endure long after they’ve moved on.

This article appears in the June/July 2024 issue of Fortune with the headline, "Where corporate America learns history lessons."

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance