The US wants to decouple its military supplies from China - but can it?

China's central role in the global supply chain has prompted the United States to initiate a series of measures to de-risk its relationship with the world's second largest economy as relations worsen.

For the US defence industry, it seems inevitable that Washington will want to go further and seek to cut out China completely.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

Whether it will work is another question, though. China now plays a central role in the global economy as a leading producer of everything from the raw materials used to make basic equipment and rare earth metals to the hi-tech equipment that is vital to the production of some of America's most advanced weapons.

When it comes to global arms exports, China accounts for a relatively modest 6.6 per cent of the market, according to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

But because China accounts for 20 per cent of total global manufacturing trade, according to Beijing's own figures, the picture is very different when looking at the components used to make weapons.

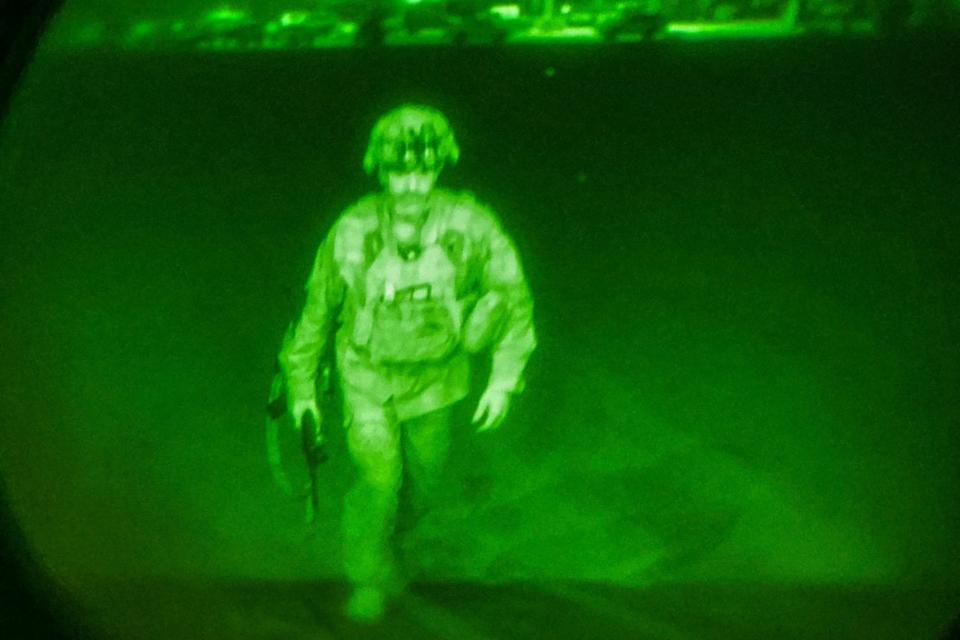

China is a major producer of components used in equipment such as night-vision goggles. Photo: Reuters alt=China is a major producer of components used in equipment such as night-vision goggles. Photo: Reuters>

If all made-in-China parts and components were removed from existing weapons as well as from the international arms industry's supply chain, it would lead to chaotic consequences for arms manufacturers around the world. Precision-guided missile makers would struggle to find enough sensors, there might not be enough infrared lenses for night-vision goggles and shortages of bulletproof fibre would have a knock-on effect on supplies of body armour.

It could also cause the war in Ukraine to suddenly stop. Much of the Western equipment supplied to Ukraine - from Javelin anti-tank missiles to Patriot air-defence systems - would stop working, and the same would apply to significant parts of Russia's arsenal, from drones to armoured vehicles.

Lockheed Martin's F-35 Lightning II, the cornerstone stealth fighter for the US and its allies, would see production lines coming to a halt while the existing fleet would run out of replacement parts.

The plane's engines and flight control systems use critical high-performance magnets, made of rare earth materials such as neodymium, dysprosium and praseodymium - all sourced from China.

As China also dominates the global rare earths processing industry there would be no immediate alternative source for these high-grade magnets.

China also has "a near-total monopoly over gallium, a critical mineral used to produce high-performance microchips that power some of the US' most advanced military technologies", the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank, said in a report last July.

It produced 98 per cent of the world's supply of raw gallium and controlled a majority of gallium extracted from bauxite, the centre said. The Rand Corporation has also said that 18 out of the 37 minerals relevant to defence applications are concentrated in China.

Advanced batteries, described by US deputy defence secretary Kathleen Hicks as "essential to thousands of military systems" such as drones and electric vehicles, is another area where China dominates the supply chain from mineral extraction, processing and component-making to battery assembly.

A report by the Pentagon earlier this year examining the US military's supply chain vulnerabilities and pointing out ways to reduce them said it provided 94 per cent of the world's lithium hydroxide, 76 per cent of cells and 76 per cent of electrolytes.

Even when it comes to basic raw materials, China holds a dominant position. The world's second biggest economy is also the world's top producer of intermediate metal products, which are vital for a whole range of weaponry - more than the next seven countries combined.

It manufactures half the world's crude steel, the largest volume of aluminium and refined copper, and exports more than twice the amount of these materials than the second-ranked producers, according to the data-gathering platform Statista.

The rapid boom in the Chinese electric vehicle industry is a further concern for Washington, which may find itself lagging when it comes to producing the military transport vehicles of the future.

Given the increasing tensions between Washington and Beijing and the obvious vulnerability in globalised supply chains highlighted by the Covid-19 pandemic, rebuilding domestic manufacturing, and reducing heavy reliance on China is a priority for the US across the political divide.

In his first month in office, Joe Biden signed an executive order to build "resilient American supply chains".

Some key industries, such as laser and microwave weapons, continue to depend on China, though direct supplies in some critical technologies, such as nuclear weapons, space, artificial intelligence and advanced communications, did see a significant drop between 2020 and 2023 despite other areas seeking a strong post-pandemic resurgence, according to defence acquisition information firm Govini.

Timothy Heath, a senior international defence researcher at the Rand Corporation, said due to the globalised production chain and complex subcontracting links, the US and its allies face a "difficult challenge" in tracing any component or part of their weapons and platforms that may have been made in China.

"However, the US government seems determined to reduce its vulnerabilities and so it has directed an extensive effort to relocate production of parts and components from China to friendlier countries," he said, adding that the success of the supply chain reshaping would depend on how quickly the US can "identify and develop alternative sources of rare earths and other critical materials".

"Both [the US and China] are likely to carry out measures to reduce risk and, if possible, decouple from the other country as a way to reduce vulnerabilities and ensure secure supply chains."

In the case of rare earths, the "friendlier countries" could be Australia, which has rich reserves of some of the critical minerals and has already formed a partnership with the US to develop "critical minerals", such as rare earths, tungsten and cobalt.

Other measures put forward include more investment into domestic manufacturing and small businesses, research and development, STEM education, industrial standardisation and cooperation with allies, to tackle the country's systematic industrial base challenges such as low capacity, technical dependence, workforce shortage, as the Pentagon's 2022 supply chain action plan suggested.

US F-35s use an array of materials and components sourced from China. Photo: AFP alt=US F-35s use an array of materials and components sourced from China. Photo: AFP>

However, China too has its vulnerabilities, most notably when it comes to chips.

The US has moved to restrict China's access to the most advanced chips and equipment used to make them, pushing allies such as Japan and the Netherlands, which make key components, to follow suit.

Although Beijing is trying to become self-reliant in this area by developing its own industry, the Chinese mainland currently imports nearly half the world's semiconductor chips, many of which come from Taiwan.

Further complicating the picture, many of these are then used to make electric products or parts that China then exports, including to US defence contractors.

Last year, 41 per cent of the semiconductors in the US weapons systems and associated infrastructure were sourced from China, according to Govini.

These can be found in some of America's most advanced weapons, ranging from warships - including its Ford-class aircraft carriers - stealth bombers, ballistic and anti-ship missiles and warplanes.

In some cases, manufacturers are also buying components, including electronics, software, fuses, detonators and data links, the Pentagon report found.

Eugene Gholz, an associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, said the US still had significant advantages, saying the relationship is "not equally dependent" as the US economy is more flexible and innovative, and it has access to more alternative suppliers than China.

He also argued that Washington was well on its way to achieving its goal of military decoupling.

"The US defence supply chain already has many reasons not to use many Chinese components and materials, so in effect, while the broader US and Chinese markets are highly interlinked through trade and investment, the defence supply chain is largely 'decoupled'," Gholz added.

"When specific instances of components from China have been identified in US weapon systems, the United States and its prime defence contractors have generally been able to find substitute sources."

This article originally appeared in the South China Morning Post (SCMP), the most authoritative voice reporting on China and Asia for more than a century. For more SCMP stories, please explore the SCMP app or visit the SCMP's Facebook and Twitter pages. Copyright © 2024 South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

Copyright (c) 2024. South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance